Basquiat the Horrible

Here in Los Angeles the banners advertising the Jean-Michel Basquiat July-Oct. 2005 exhibit at the Museum Of Contemporary Art (MOCA) have been ubiquitous.

That no one knows how to pronounce the name of the deceased artist only adds to the carefully manufactured aura of mystique that surrounds his legacy. I’ve heard “Bäs k-ät”, “Bas-KEE-ah” and several malformed variants – but no matter, we all know who is being spoken of.

Now that the MOCA exhibit is closed and everyone in the postmodernist peanut gallery has heaped praise upon the deceased, it’s my turn to say a few words.

Art world elites and critics have crowned Basquiat as one of the “most important artists of the 20th Century,” and so you better go along with the crowd if you don’t want to be seen as utterly clueless and hopelessly old fashioned – even if you can’t pronounce the artist’s name. Before you begin hurling invective at me for daring to say “the Emperor has no clothes,” at least let me explain why I find Basquiat’s works insufferable and inadequate.

I must first point out that my critique of Basquiat is not based upon a Eurocentric view of art and culture. I have learned from and extolled the genius of African American artists ever since I was a teenager in the 1960’s; I wouldn’t be the artist I am today had it not been for the influences of some extremely talented Black artists.

I won’t mention the opinions of those who broadly and regularly condemn modern art. They have a great aversion towards the work of Basquiat, and I have little in common with their point of view. In part my critique is aimed at the liberal arts community, who essentially created Basquiat.

That the artist became successful in a lily white art world might have more to do with the attitudes of gallery owners, critics, and collectors (who, let’s be honest, are largely white males), than to the actual talent possessed by the artist. With all of the amazing Black/Latino artists in the United States, how is it that Basquiat has become the sole exemplar and super-star?

Born in Brooklyn of Puerto Rican and Haitian parents, Basquiat started his artistic career as a tagger, spray-painting graffiti images on buildings under the moniker of SAMO (“Same Old Shit.”) There were taggers in Brooklyn with much more skill and talent than Basquiat, but they were not to be graced with pop idol status by the art world.

Basquiat’s skills in draftsmanship were virtually non-existent, and never exceeded a halting and nervous stick figure style, but elite art opinion has done away with drawing ability as a prerequisite to being an artist. Basquiat’s untrained and unskilled hand was and is heralded as an authentic voice tapping into African roots, as if African art can only be primitive and naïve.

SAMO was a frank and honest nickname that described what Basquiat was doing, and he should have kept the alias as it so aptly made clear what he was all about, namely… celebrity. But the exigencies of fame and notoriety can be cruel, and one must be properly packaged to be a success, so “SAMO” fell by the wayside and “Basquiat” became his professional name.

In 1983 the former SAMO would meet Andy Warhol, and Basquiat’s entry into elite art circles and history became assured. He had been productive for only eight years when his heroin addiction caught up with him; he overdosed and died at the age of twenty-seven in 1988. That he was little more than a drug addled street artist without training and possessing just a modicum of talent would not be a hindrance to advancement in today’s art world, quite the contrary.

I’m well aware of the need Black Americans have for a positive role model in the field of art, and for an artistic expression that reflects their life experience and speaks directly and honestly to them. But Basquiat is not that role model and his confused postmodernist smudges and scribbles are a sham. If we were talking about music, Basquiat would be closer to Snoop Dog than to Winton Marsales.

I accept Basquiat’s body of work for what it is, what I can’t tolerate is the grotesque hype that surrounds it. I don’t find Basquiat’s better pieces entirely unpleasing or uninteresting; Basquiat’s tragic voice was a reflection of the times, disjointed, incoherent, shattered and babbling. His visual language was gibberish to match the inanities of the 1980s, but I see no genius in that.

We are offered Basquiat’s example as a standard to aspire to, but by whom, and does anyone honestly believe there is no better model to emulate? The larger questions are, who gets to appoint the leading lights of the art world, and why do we fawn over them so unquestioningly?

It was of course Andy Warhol who said “Good business is the best art,” a thought that expresses the very antitheses of what I think art is about, but perfectly explains Basquiat’s enormous success; it should go without saying that the collaborative works between Warhol and Basquiat were certainly good business.

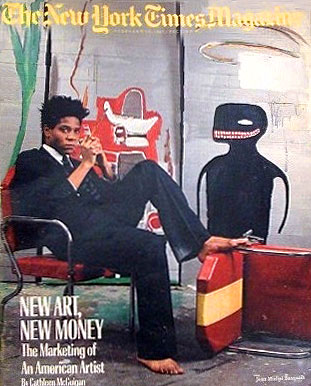

In 1985 The New York Times Magazine featured Basquiat on its cover with the headline, “New Art, New Money: The Marketing of an American Artist.”

That the traveling Basquiat exhibition and its attendant website is sponsored by the JP Morgan Chase Bank, says just about everything that needs to be said.

From its origins as one of the original robber baron companies that monopolized American railroads, steel production and banking, right up to its present role as one of the world’s globalized financial institutions with well over a trillion dollars in assets, JP Morgan Chase Bank can make or break anyone or anything it so desires.

Interestingly enough, one could once find on the JP Morgan sponsored website, the following proclamation concerning Basquiat’s work; “There is no single, fixed interpretation of any of his paintings or drawings.” Which is just the type of art the ruling class likes to promote.