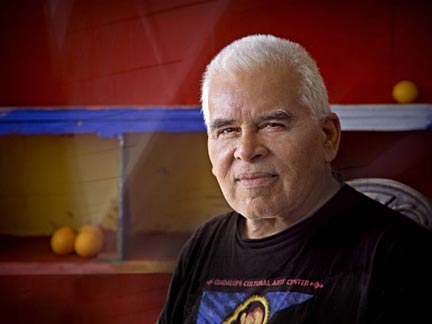

Gilbert “Magú” Luján: 1940-2011

On Tuesday July 26, 2011, I received the devastating news that my friend, Gilbert “Magú” Luján, died the previous Sunday at the age of 70.

My immediate reaction was to openly weep, for this was not just the loss of a personal friend and treasured colleague, but an overwhelming blow to the Chicano arts community of Los Angeles and beyond. Magú was known to one and all in that expansive circle, and while not everyone was in accord with his views, I believe we all benefited from his overall artistic vision, philosophy, and dedication to Chicanarte (Chicano art).

I cannot recall precisely when I first became aware of Magú and his works, as an artist/activist he was ever-present and highly regarded; I enjoyed his art long before I had the pleasure of making his acquaintance, which was sometime around 2003.

Appreciating my art and writings, Magú invited me to attend one of his Mental Menudo discussion groups, where Chicano artists gathered to discuss art, culture, and politics. I ended up attending several Mental Menudo gatherings, some were intimate get-togethers consisting of just a few close associates, others were mass assemblies of up to 70 or more artists; all were lively and sometime fractious dialogues regarding Chicano art and aesthetics. A natural leader due to his gregarious and personable manner, not to mention his respected standing as an artist, Magú usually chaired the meetings; however, he was also one of the most democratically minded persons I ever knew, and always sought to place decision making power in collective hands.

While artists, writers, musicians, photographers, activists and many others discussed all things Chicanismo at Magú’s Mental Menudo talks, he always avoided articulating a set definition for Chicano art. Yet, Magú definitely held his own opinion regarding what constituted Chicano art, he merely did not wish to impose that vision on others. As he once wrote to me in a 2006 e-mail; “We have a wide range of expertise and some incompetence, a broad spectrum of knowledge and some ignorance…it is a microcosm of the world. Since getting involved with this movimiento I have realized the variation of individuals make a strong body – but as a whole.” Magú believed that Chicano art was deeply rooted in the wide collective experience of Mexican-Americans, as he saw things it was a continually evolving aesthetic and it was up to all of us to create, shape, and advance the school he dedicated his life to.

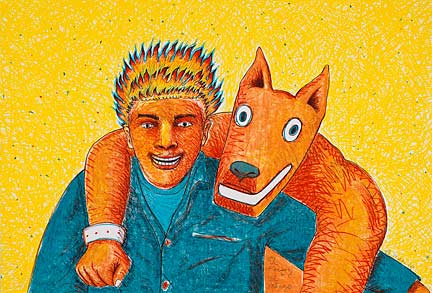

Magú’s own works incorporated graffiti, folk art, pop imagery, figurative realism, abstraction, and ancient Mesoamerican imagery into a whimsical and highly individualized style. On the face of it his works were pictorially naive or “primitive,” but they were dense with meaning, coded visual language, and narratives concerning place, personal chronicles, and a people’s collective history.

Soon after his invite to join the Mental Menudo circle, Magú and I became fast friends and confidantes, and over the years we shared many deep philosophical conversations regarding the world and our place in it as socially conscious artists. On many occasions Magú would telephone me from out of the blue, greeting me with a warm “Hermano!” and always wanting to talk about cultural matters; our phone conversations would sometimes last for hours. Early in our friendship Magú told me that he had once been offered a very large sum of money by the fast food giant, McDonald’s. The mega-corporation was seeking to penetrate the “Hispanic” market, and wanted to enlist Magú’s services as a well-known Chicano artist to help build confidence in the burger chain’s “brand.” He flatly refused the offer, earning my eternal respect and admiration.

Magú and I never argued, though we had our differences. Initially attracted to Chicanarte because of its innate social-political core, I always insisted that a concern for social justice and a didactic approach to art making was a strong component of the Chicano school, a point Magú in no way contested. He agreed with me that all art was political, and that in the context of our present society it could not be otherwise, but his artwork took a nuanced, seemingly “apolitical” approach to social matters. Likewise, I never disagreed with him that spiritual concerns were also a major element in Chicano art, and by “spiritual” I mean those ethereal affairs that have so captivated and befuddled humanity; questions regarding death, the search for meaning in life, and what we refer to as the “soul.” Magú and I both concurred that a profound humanism animated Chicanarte.

In 2010 Magú was invited to speak at an L.A. forum on the life and work of Mexican Muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros, an artist that long inspired the two of us. The event was titled Freedom of Speech and Censorship, and it took place on August 20, 2010 at the L.A. headquarters of the Mexican American Legal Defense & Educational Fund (MALDEF). The night prior to the event Magú made one of his periodic phone calls to me, this time longing for insights into our mutual hero Siqueiros. It was to be another of our extended phone conversations, but when it was finished Magú was eager to address the forum; he later told me the event went well, and that he spoke on the influence Siqueiros had upon contemporary art in L.A.

I could cite innumerable examples of how Magú’s art touched people, but here I will simply mention one public art commission he created for the City of Los Angeles. Some 200 of his hand-painted ceramic tiles are set into the wall at L.A.’s Metro Rail Red Line station at Hollywood & Vine, an underground train depot that services tens of thousands of people on a daily basis. Magú’s fanciful drawings on tile feature anthropomorphized animal Lowriders cruising past Aztec temples on Hollywood Boulevard, pre-Columbian speech scrolls float from their mouths as they motor through a Southern California scene decorated with all manner of Mesoamerican symbols and references. For Chicanos, the art of Mesoamerica in general and the art of the Aztecs in particular, stands as a root aesthetic – this cannot be overstated, and it must be taken into account when considering the fanciful art of Gilbert “Magú” Luján.

It pleases me greatly to know that untold millions of people will view Magú’s Metro artworks for as long as the rail-line is in existence. If for no other reason he should be known for that particular installation, and the city is blessed to have it.

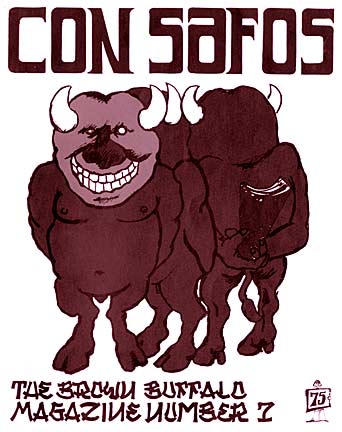

One of his earliest marks as a public artist was made as a student when he contributed artworks to Con Safos Magazine, an influential underground 1960’s publication in L.A. that became a voice of el movimiento, the burgeoning Mexican-American cultural and political movement. Con Safos is Chicano slang (or Calo), for “the same to you” or “back at you”. Decades before “graffiti art” became just another hot commodity in the art market, Chicano graffiti writers would sign their creations with “C/S” (short for con safos), basically stating “I am impervious to your insults.” It was that defiant spirit that filled the pages of the original Con Safos Magazine.

The winter 1971 edition of Con Safos, published a drawing by Magú as its cover – an illustration for the publication’s serialized presentation of The Autobiography of a Brown Buffalo, a biographical story by Chicano lawyer, Oscar Zeta Acosta. The issue also included a reprinted article from the Los Angeles Times, Mexican American’s Problems With The Legal System Viewed, authored by Times reporter Ruben Salazar, who had recently been killed by the L.A. Sheriff’s Department during their attacks on the National Chicano Moratorium March against the Vietnam war in East L.A. on August 29, 1970. The issue also published Magú’s essay, El Arte del Chicano (Art of the Chicano), which in part stated:

“There are some who would say that the Chicano experience is lacking in those elements that lend themselves to universal artistic expressions. This is a narrow and shortsighted view. One only has to examine the barrio to see that the elements to choose from are as infinite as any culture allows.”

Magú’s pointed commentary is as pertinent today as it was in 1971. Already in publication before East L.A.’s historic Chicano student walk-outs of 1968, Con Safos – through its artworks, poetry, provocative essays, and photography – helped set the tone for the social explosions of that period, and Magú was there from the beginning. The rest, as it is said, “is history.”

On August 13, 2011, the dA Center for the Arts in Pomona, California will present a major retrospective of Magú’s art, called Cruisin’ Magulandia: A Benefit for the Preservation of a Legacy. The exhibition and sale of Magú’s paintings, prints, drawings, and sculptures will continue until August 30, with all proceeds going towards the preservation of Luján’s legacy and estate. The Los Angeles Times has published an obituary on Magú. Not to be missed, a short but quite wonderful interview with Magú can be found on Vimeo. In closing, I offer an ancient Aztec poem to brother Magú and all those who mourn his passing:

My heart listens to a song:

I start to weep; I am wracked with sorrow,

We walk among the flowers:

We have to leave this earth:

We are living on borrowed time:

We shall go to the House of the Sun!

Let me wear a garland of many-colored flowers:

Let me hold them in my hands;

Let me flower in my garlands!

We have to leave this earth:

We are lent to each other:

We shall go to the House of the Sun!