Guatemala: Voices of Justice

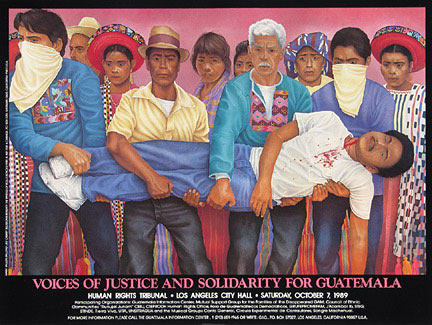

In 1989 the Guatemalan Information Center (GIC), a human rights organization founded by a group of Guatemalan exiles living in Los Angeles, commissioned me to create a poster.

Its purpose was to announce the Guatemalan Human Rights Tribunal, a public forum the GIC was planning to hold in the Council Chambers of Los Angeles City Hall on the subject of the war then raging in Guatemala. I had been closely following the unfolding tragedy in that Central American nation since the late 1970s, and my concerns were reflected in the art I was making in those days.

I created the poster for the GIC free of charge, and the widely distributed artwork brought hundreds of people to the group’s City Hall event. At the tribunal, eyewitness accounts of the war were provided in testimonies from Guatemalan labor union activists, clergy, representatives of indigenous peoples, students, human rights workers, and others. My collaboration with the GIC was motivated by the reports I had been reading about the plight of Guatemalans – like the following story involving the Mayan village of Las Dos Erres in the north of Guatemala.

On December 5, 1982, the hamlet of Las Dos Erres was visited by unspeakable horror when Special Forces commandos of the U.S.-backed Guatemalan army attacked the sleepy village – which the Guatemalan military government suspected was sympathetic to the country’s left-wing guerrilla movement.

Beginning on that fateful December day the commandos of the “Kaibil” Special Forces commenced the systematic butchering of some 350 men, women, and children – nearly the entire population of the Mayan settlement. The massacre would continue for three days, and only two five-year-old boys would survive the bloodbath.

I am writing about this now because on May 5, 2010, officers from the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency arrested a former member of the Kaibil Special Forces who had been living in Palm Beach, Florida as a naturalized U.S. citizen. Gilberto Jordan was charged with lying about his role in the Las Dos Erres massacre in order to obtain U.S. citizenship. According to ICE, Jordan admitted “that he participated in the killings,” and that he stated “the first person he killed was a baby, whom he murdered by throwing into the village well.” The U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Florida, Wifredo A. Ferrer, said, “The acts alleged in this complaint are horrific” and that “we will not provide shelter and cover to those who lie about their criminal past, especially human rights abuses, to gain U.S. citizenship.”

This past February, immigration agents also arrested former Kaibil soldier Santos Lopez Alonzo in Houston, Texas. Picked up as an undocumented day laborer, Alonzo is alleged to have held women and children at gunpoint as they were being murdered and thrown into the village well at Las Dos Erres. Immigration authorities are also seeking two other former Kaibil soldiers known to be hiding in the United States who were present at the Las Dos Erres massacre – Jorge Vinicio Sosa Orantes, a second lieutenant in the Kaibiles who is alleged to have murdered civilians by smashing in their heads with a sledge hammer, and Pedro Pimentel Rios, a Kaibil commando alleged to have raped a number of girls and women before they were slaughtered.

Writing for the Global Post on May 5, 2010, reporter Matt McAllester summed up the history of the massacre at Las Dos Erres – in all its grisly detail – in his article, “U.S. rounds up Guatemalans accused of war crimes.” But McAllester’s piece also raises a number of important questions regarding the mass executions, not the least of which is the fact that the U.S. government trained and armed the Guatemalan army responsible for such mass killings.

In his article, McAllester notes that de-classified cables sent from the U.S. Embassy in Guatemala to the U.S. State Department in Washington, D.C. during the years 1982 and 1983, confirm that the U.S. government knew the Guatemalan army had carried out the massacre at Las Dos Erres, “yet the School of the Americas began to welcome new instructors and students from the army only days after the killings.”

McAllester’s report stated that just a month after the atrocity, the Kaibil commando Pedro Pimentel Rios – the one who allegedly committed mass rape – became an instructor at the Pentagon’s School of the Americas in Panama. Not only that, McAllester wrote, “He was given an Army Commendation Medal for meritorious service by the then-U.S. Secretary of the Army John Otho Marsh in 1985.”

The massacre at Las Dos Erres was not an aberration. When the 36-year war between leftist guerrillas and the U.S.-supported Guatemalan army ended with a peace accord in 1996, over 200,000 Guatemalans had perished. In 1999 Guatemala’s Historical Clarification Commission, a UN-sponsored truth and reconciliation commission, released a report titled “Memory of Silence” that found indigenous Maya accounted for 83% of the dead, and that 93% of the victims had been murdered by government armed forces. The commission’s report concluded that the U.S.-backed Guatemalan army had identified “the Mayan population as the internal enemy,” and that the army’s relentless assaults upon indigenous communities comprised “acts of genocide.”

There are those Americans who were long aware of the U.S. government’s role in the Guatemalan civil war of the 1980s, and I count myself amongst those who not only attempted to bring attention to America’s responsibility for the violence, but actively sought to end U.S. military aid to the homicidal maniacs that ruled the Central American nation at the time.

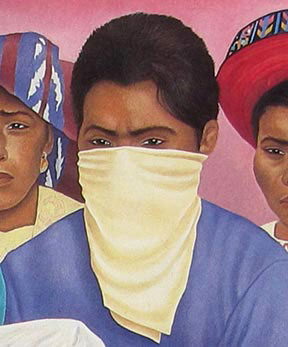

I worked closely with the Guatemalan Information Center in developing the poster announcing their Human Rights Tribunal. GIC members provided me with background information and materials needed to create my artwork. However, it was the compelling personal testimonies from GIC members that I found most valuable. Many had taken flight from their homeland out of fear they would be murdered by government sponsored death squads. Each had an anguished story to tell; soldiers stopping people at checkpoints and arbitrarily arresting individuals who would never be seen again; people who would disappear, only to be found dumped in a public place, their bodies displaying telltale signs of torture, mutilation, and execution by death squads.

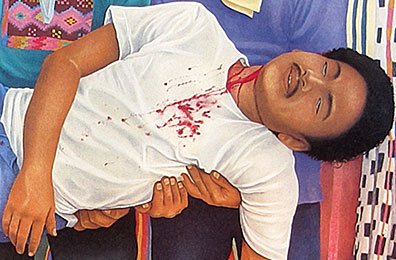

After hearing the personal stories of Guatemalan Information Center members, I decided upon creating a 3 x 5 foot chalk pastel drawing depicting campesinos carrying a wounded man shot by government troops. Upon completion, the chalk drawing titled “Voices of Justice” was printed as the full-color, 11 x 15 inch offset poster that announced the Human Rights Tribunal. During the event at L.A.’s City Hall, the original chalk drawing was displayed in the City Hall Council Chambers.

Due to the fearsome level of repression and wholesale murder of political opponents practiced by the regime of President Lucas Garcia in the late 1970s, U.S. President Jimmy Carter cut overt military aid to Guatemala in 1977. Garcia was deposed in a 1982 coup d’état led by General Efrain Ríos Montt, who was a graduate of the U.S. School of the Americas.

In 1983 the Reagan administration lifted Carter’s arms embargo to arm the fanatically anticommunist military junta led by Montt. An unprecedented level of barbarity was unleashed upon Guatemala by Montt, who let loose a wave of political kidnappings, assassinations, torture, and a scorched earth policy that totally annihilated some 600 Mayan Indian villages.

It cannot be emphasized enough that the Reagan administration supported the savagery by funding, training, and equipping the Guatemalan army, as well as giving the military dictatorship full political support. In the midst of the Guatemalan army’s campaign of mass extermination against the indigenous population, President Reagan visited General Montt in Honduras. On December 4, 1982 – just a day prior to the massacre at Las Dos Erres – Reagan acclaimed Montt as a leader who was “totally dedicated to democracy,” further proclaiming that the junta leader had falsely been given “a bum rap” by human rights activists.

In today’s Guatemala there are purportedly over 100 secret graveyards where government soldiers and their death squad allies buried the many thousands of non-combatant civilians they murdered in a killing spree meant to rid the country of “communist subversives.” But those dead do not rest easy, and their tales are now just beginning to come to light in the present. Miguel Angel Asturias (1899-1974), Guatemala’s Nobel Laureate for Literature, was quoted in the prologue of Guatemala’s Historical Clarification Commission report for saying the following: “The eyes of the buried will close together on the day of justice, or they will never close.”

I am frankly stunned at how quickly the war in Guatemalan has been forgotten – at least by those who were not direct victims of the mayhem. What was once an international cause célèbre has been quietly put out of mind; we have moved on to Iraq and Afghanistan. But reality has an unpleasant way of stabbing through our most formidable walls of denial. The poster I created for the Guatemalan Information Center in 1989 continues to reverberate in the present – the arrests of murderous Kaibil Special Forces in the U.S. are reminder enough of that.

View a large version of the poster, Voices of Justice.

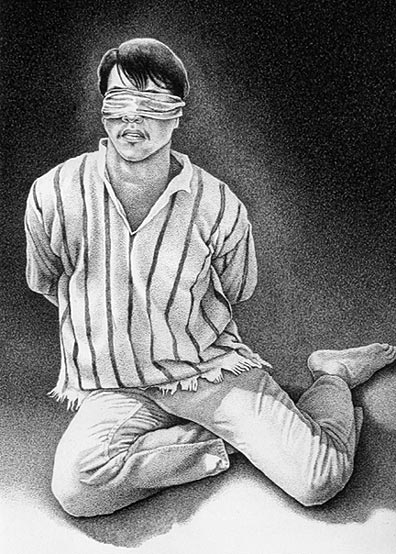

View a large version of the drawing, Prisionero.