Echoes of Weimar

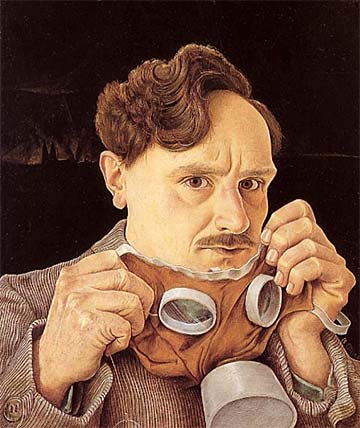

Barthel Gilles (1891-1977) was one of those artists overlooked by history, he was a fabulously talented painter who lived during the rise and fall of Germany’s Weimar Republic (1919-1933), not to mention the ascendancy and demise of the Nazi regime.

An undeniably idealistic and passionate artist, he was not left unscathed by the terrible days he passed through; one could say he was left broken by them. I wrote briefly about him and his 1930 painting Ruhrkampf (Ruhr Struggle) in 2001, but I feel compelled to say more about the life and work of this little known artist.

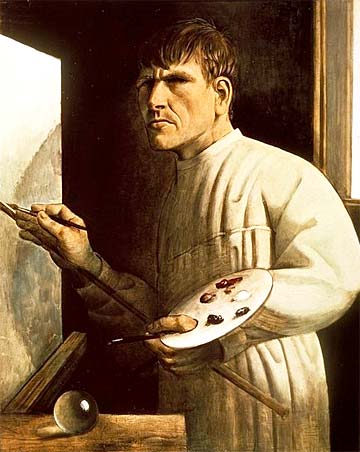

Otto Dix (1891-1969) should be familiar to readers of this web log, since he is one of the most celebrated of all German Expressionist artists.

My conviction that there is much to learn from the German Expressionist movement, mixes with my sense that we are living in times reminiscent of the Weimar period; an epoch marked by the eroding of democratic institutions and cultural life, economic collapse, endless war, corrupt monied elites and professional politicians that are completely out of touch with common people. Add the foibles of late capitalism in the early 21st century, and suddenly this article is not so much about Gilles or Dix and the moral, political, and aesthetic questions they and their compatriots faced; it becomes a matter of how artists are responding to today’s world situation.

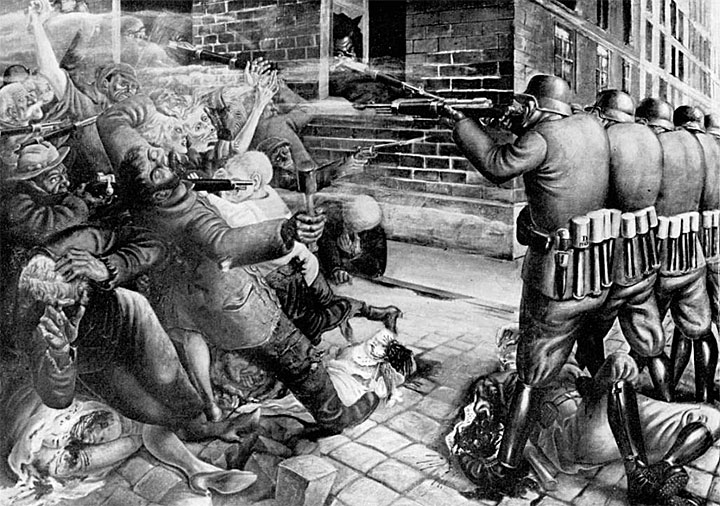

In 1927 Otto Dix painted Straßenkampf (Street Fight), a shocking representation of the ferocious armed clashes that took place between militant left-wing workers and right-wing militias in the years just prior to Nazism.

Barthel Gilles painted a similar work in 1930 titled Ruhrkampf (Ruhr Struggle); his masterwork was based upon the Märzrevolution (March Revolution) staged by German workers in 1920. But what were the real-world events that so captivated the imagination – and outrage – of these two artists?

The street battles that induced Gilles and Dix to record their indignation have mostly been long forgotten, even in Germany, but the political dynamics of the events continue to resonate in our present. To fully comprehend the two paintings examined in this article, one needs to understand a bit of German history.

When Otto Dix painted Straßenkampf (Street Fight) in 1927, he placed the viewer in the midst of a bloody and desperate mêlée between an armed populace and soldiers. His Goyaesque work of art depicted the ruthless class struggle then taking place in Germany; bloodletting that pitted impoverished workers, war veterans, and various left-wing groups against the very forces that would become the Nazi’s political base – militarists, xenophobes, ultra-nationalists, racists, and extreme rightwing anti-communists.

The painting shows a throng of disorganized civilian rebels, most of which are not men of fighting age. Shrouded in a haze of gun smoke and armed with a hodgepodge of weapons, they are desperate to get at their enemies, a unit of heavily armed paramilitary Freikorps troops. Though offering valiant resistance, the crowd is being decimated by deadly precision volleys of rifle fire from the Freikorps soldiers, who were largely battle hardened WWI veterans.

The mob buckles under the withering barrage; blood-splattered women with horrific gunshot wounds are crushed beneath the crowd; two young blonde women raise their hands in dismay; a bearded rebel fighter attempts to fling a captured “stick grenade” at the Freikorps but is fatally shot before he can toss it. In juxtaposition to the routed multitude the disciplined Freikorps seem unyielding and invincible, though one of their own lay dead at their feet, his right arm a bloody pulp. Dix’s painting was as prescient as it was horrific. He sardonically signed his painting by placing his monogram on a grenade hanging from the belt of the soldier closest to the foreground.

What specific event Dix was showing in his painting is unclear. In the early 1900s Germany was impoverished, exhausted from war, and on the verge of revolution. Left-wing rebels regularly battled with those right-wing ultra-nationalists who eventually would form the Nazis; as the hapless “liberal” Weimar government played at being centrist (all the while seeking the support of Weimar industrialists and the rightist German military). Perhaps the painting was a depiction of the Weimar reprisals made against the Munich Soviet Republic established in Bavaria in 1919. Maybe it was a portrayal of state repression aimed at the 1919 Spartacist uprising, when communists attempted to set off a revolution in Berlin. Whatever the inspiration, Dix encapsulated the agony of the Weimar years in the gory scene. The few references one can find about the painting list it as “destroyed or lost”. Sadly, there is but one black and white photo of the painting (year and photographer unknown).

It should be remembered that once the Nazis came to power in 1933, they removed Dix from his teaching position at the Dresden Art Academy, prohibited him from exhibiting in Germany, mockingly placed his paintings in the Nazi organized Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibit, and removed two hundred and sixty of his artworks from museums. In fascist parlance his work was “un-German” and responsible for helping to undermine “the will of the German people to defend themselves.” It is a fair assumption that Straßenkampf was confiscated by the Nazis and later destroyed for its portrayal of German soldiers.

Barthel Gilles and Otto Dix both painted in the difficult medium of egg tempera. Used for centuries, egg tempera was the medium of choice for European artists until the introduction of oil painting in the 15th century. Because of its handling qualities and relative ease of use, oil would eventually displace egg tempera as a preferred painting medium. However, egg tempera did not entirely disappear. Old masters used it as an “underpainting” because it dried so quickly, completing their paintings with glazes of oil paint. German master painters like Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) and Hans Baldung Grien (1484-1545) excelled at mischtechnik, the “mixed technique” mentioned above.

Leading lights in the Neue Sachlichkeit (“New Objectivity”) school of German Expressionism that flourished during the ill-fated Weimar Republic, Gilles and Dix shared an infatuation with Old Master paintings. Inspired since his youth by the likes of Dürer and Hans Baldung Grien, Dix created some of his most well-known artworks in mixed technique. While perhaps better known for his radically severe expressionist works, Dix could paint on par with a German Renaissance Master like Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553); ample evidence is provided in Triumph des Todes (Triumph of Death) a 1934 allegorical work Dix painted after the Nazis fired him from his professorship at the Dresden Art Academy. In fact Dix once said, “I am not a gifted pupil of Rembrandt, but rather of Cranach, Dürer, and Grünewald“.

A year before painting Ruhrkampf, Barthel Gilles had become a member the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), as well as joining the Assoziation Revolutionärer Bildender Künstler Deutschlands (ASSO – “Association of revolutionary visual artists of Germany”) a group of artists associated with the KPD. Notables in the group included the likes of George Grosz, Curt Querner, Otto Nagel, Paul Fuhrmann, and Hans Grundig).

Gilles’ 1930 Ruhrkampf (Ruhr Struggle) was based upon the March Revolution of 1920. That uprising was the response of workers to the Kapp Putsch, an attempted military coup against the young centrist Weimar Republic that was organized by an extremist nationalist named Wolfgang Kapp and joined by large segments of the armed forces. The Weimar government ordered the army to suppress the coup, but the command was refused. As rightist pro-coup troops marched on Berlin, the government fled to Stuttgart. The Kapp Putsch collapsed in four days because a massive nationwide strike against it paralyzed the country. However, the failed coup set off a series of events that would forever alter German society.

After the Kapp Putsch affair, large numbers of Germans who had defended the Weimar Republic came to view the Social Democratic government as an obstacle to the completion of the 1918 November Revolution that overthrew the monarchy of Kaiser Wilhelm II.

Insurrection became the order of the day as revolutionary workers and former soldiers took over various cities; eventually some 80,000 leftwing workers would organize themselves as the Red Ruhr Army to control the entire Ruhr industrial area of North Rhine-Westphalia. In a fateful decision, the Social Democrats of the Weimar government sent in the army – the very same army that refused to defend the Weimar regime – and the Ruhr uprising was crushed with brutal force. Thousands of rebels were killed. From that point on, German leftists found it impossible to work in partnership with the Social Democrats, a fact that splintered opposition to the rise of Hitler. That is the background narrative of Gilles’ painting.

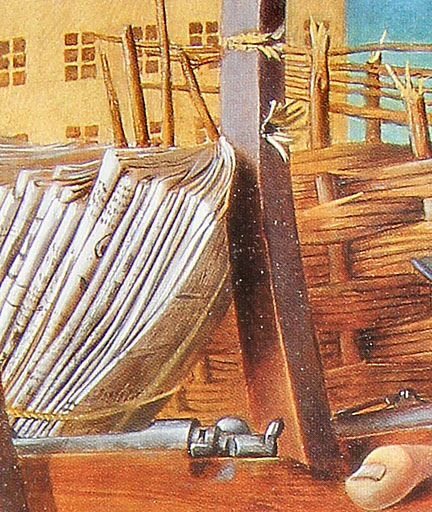

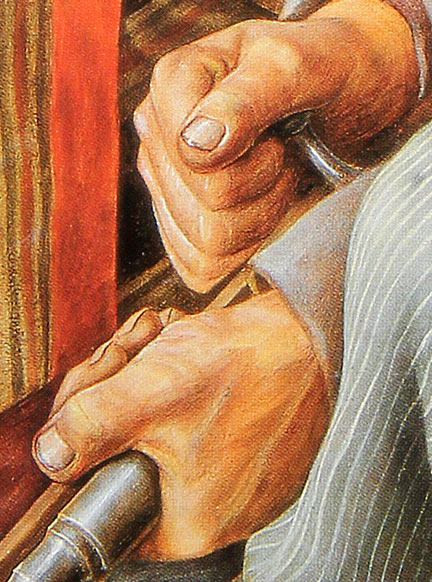

Ruhrkampf is a technically brilliant painting, and Gilles deftly employed the Old Master method of painting oil glazes over an egg tempera underpainting.

Compositionally, the work focuses on three insurrectionists from the March Revolution cramped together with their rifles behind a makeshift barricade.

The three form a curve that ends with the agitated looking fellow in the foreground. He works the bolt action on his Steyr-Mannlicher M1895 rifle, the standard service rifle for soldiers of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in WWI that would later be used by Weimar era soldiers and to a lesser extent by the Nazis. The worker in the center of the painting is also armed with an M1895, which is easily identified by its unique shaped trigger guard assembly and magazine. That Gilles included these technical details shows what a stickler he was for accuracy.

Gilles’ exactitude is found in other details of Ruhrkampf; the Neues Bauen (New Building) modern architecture barely discernable at the skyline; the working class attire of the men (precise right down to the embroidery on their caps); even the items making up the barricade add to the narrative. One can see wicker basketry, box springs from a bed, an upside-down wooden chair, and a bound stack of newspapers.

The papers in the painting indicate two things; that the workers were literate and well informed (at the time German newspapers ran the entire political gambit from hard left to extreme right and everything in between); and that experience taught the workers that tightly bound bundles of newspaper made effective bullet stops.

The three rebels are under fire from German soldiers mobilized against them by the Weimar government; if one looks closely bullet holes can be seen in the legs of the chair, and splintering the top of the wicker basket.

Even the cap of the worker in the top right corner has a bullet hole in it.

Given the fact that Germany was experiencing mass insurrectionary violence between the left and those on the extreme right, the Weimar government was terrified of an armed populace. The Social Democrats of the Weimar regime used rightwing Freikorps troops and the German army to brutally crush the left and communist movements in Germany – killing thousands. The Weimar gun control laws of 1928 were not so much used out of a concern to “stop the bloodshed”, as they were a desperate attempt to increase the political control the regime had over a population increasingly in revolt.

In his article, Nazism, Firearm Registration, and the Night of the Broken Glass (PDF file), Attorney at Law and conservative activist Stephen P. Halbrook wrote about Weimar gun control laws, noting that the April 12, 1928 Weimar Law on Firearms and Ammunition required that licenses issued by police departments would be necessary in order for an individual to obtain or carry a firearm. That law was amended in 1931, authorizing that all guns must “be registered with the police authorities.” The Weimar decree further authorized the police to confiscate weapons in order to foster “the maintenance of public security and order.” Those who failed to register their guns, or surrender them to the authorities when told to do so, could be jailed for “not less than three months.” [1] Halbrook also documented that Weimar law stated that “Licenses to obtain or to carry firearms shall only be issued to persons whose reliability is not in doubt, and only after proving a need for them.” [2]

Meant as a rebuttal to Halbrook’s research, liberal University of Chicago law professor Bernard E. Harcourt wrote his 2004 treatise on gun control in Nazi Germany, Hitler and Gun Registration. Harcourt conceded that “the Weimar Republic passed very strict gun control laws essentially banning all gun ownership,” and that on January 13, 1919, the Weimer government “enacted legislation requiring the surrender of all guns to the government. This law, as well as the August 7, 1920, Law on the Disarmament of the People passed in light of the Versailles Treaty, remained in effect until 1928, when the German parliament enacted the Law on Firearms and Ammunition (April 12, 1928).” [3]

Harcourt’s article correctly discounted the myth that Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party disarmed the German people, pointing out that it was the Social Democrats of the Weimar Republic that disarmed them. The Weimar Government’s gun registration program was so effective that once the Nazi’s seized power, they simply used Weimar records on gun owners to put their own version of gun confiscation into practice. With the political opposition disarmed, banned, imprisoned, driven into exile or murdered, Hitler’s regime expanded the Weimar gun laws by writing their own in 1938 – which of course forbad Jews and regime opponents from owning firearms. While Halbrook and Harcourt are ideological adversaries and they reach different conclusions, their insights into Weimar era gun bans are penetrating and informative.

There is one last wrinkle in the saga of Barthel Gilles, it is a miserable, shameful, and lamentable fact. While the majority of his colleagues in Expressionist and left political circles refused to give in to the Nazis, displaying their open or clandestine resistance by various means both large and small – Gilles appears to have collaborated with the fascist regime.

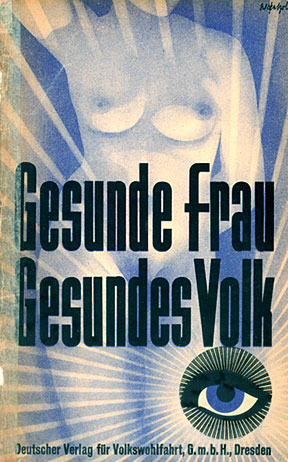

With their seizure of power in 1933, in order to guarantee their absolute control over all aspects of cultural and artistic life in Germany, the Nazis established a “National Chamber of Culture” headed by Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels. Two of the Nazi organized art exhibitions for 1933, West-front (Western Front) and Gesunde Frau, Gesundes Volk (A Healthy Woman – A Healthy People), listed Barthel Gilles as a participating artist.[4] While I have no information about the former, I can tell the reader something about the latter.

A Healthy Woman – A Healthy People was originally an exhibit curated by the Deutsches Hygiene-Museum of Dresden, founded in 1912 as an institution dedicated to “public understanding of sciences and humanities.” Once the museum came under the direct control of the Nazis in 1933, that mission changed. The Nazis altered the exhibit A Healthy Woman, to promote their theories on racial hygiene and eugenics. It became a traveling exhibit, its first showing was outside of Dresden in the city of Cologne. I can find no record of what Gilles exhibited in the show.

In 1938 Gilles frequently took part in exhibits organized by the Deutsche Arbeitsfront (German Labor Front or DAF), the Nazi established “trade union” that replaced all worker’s organizations and unions after such groups had been abolished by the fascists in 1933. The DAF put an emphasis on combating liberalism and communism, as well as generating support for the Nazi state among the working class.

A powerful arm of the DAF was the Gemeinschaft Kraft durch Freude (Community Strength Through Joy – KdF). Responsible for arranging leisure pastimes for workers, the Strength Through Joy branch of the Nazi labor front organized art exhibits, concerts, cruises, and other cultural activities. The KdF was also responsible for developing the Volkswagen (People’s Car). Historic records show Barthel Gilles listed as a “regular” participant in Strength Through Joy art exhibits [5], though I can find no record of what he exhibited.

Even if appalled by Gilles’ collaboration with the Nazis, it is problematical to judge him. Believe it or not, the Nazi curated exhibit A Healthy Woman – A Healthy People actually toured the U.S. from 1934 to 1943. In fact, it was housed by the Museum of Science in Buffalo, New York, until 1943. [6] What does that say about abetting Nazi ideology? Apparently thousands of Americans viewed and enjoyed the exhibit, until the museum decided to permanently take the show down due to sensitivity over the then two-year long war with Nazi Germany.

As for Gilles’ exhibiting in Nazi organized exhibits, aside from exile, what other opportunities did German artists have for showing their works? Since the Nazis tightly controlled the museum and gallery system as well as all other aspects of cultural production, those who criticized the regime were hounded, banned from making art, imprisoned or worse. How many of us could withstand such persecution? Ultimately it is a question of one’s own humanity, do you keep it by resisting or lose it by consenting to the most despicable outrages. That Gilles collaborated with a genocidal regime to save himself is his shame, that many of us today accept the unacceptable is ours.

####

PLAGIARISM NOTICE:

Mr. Gunther Stephan (aka ” Kraftgenie”), who administers the so-called Weimar website, has plagiarized my original writings regarding German Expressionist artists. Without authorization, he lifted my original text on Barthel Gilles (written 2001), and used it without credit or link for his 2010 Barthel Gilles post. Stephan also stole verbatim, sections of my writings on Gert Wollheim (Stephan’s plagiarized version), and Curt Querner (plagiarized version). If my most recent article about Barthel Gilles and Otto Dix shows up on Stephan’s Weimar website, at least now you will know who the genuine author is.

####

[1] Stephen P. Halbrook: “Nazism, Firearm Registration, and the Night of the Broken Glass.” (PDF file). Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law, No. 3. (2009)

[2] Stephen P. Halbrook: “Nazi Firearms and the Disarming of the German Jews.” (PDF file). Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law, No. 3. (2000)

[3] Bernard E. Harcourt: “Hitler and Gun Registration.”

[4] Sergiusz Michalski: “Neue Sachlichkeit: Malerei, Graphik und Photographie in Deutschland 1919-1933.”

[5] Sergiusz Michalski: “Neue Sachlichkeit: Malerei, Graphik und Photographie in Deutschland 1919-1933.”

[6] Susan Currell, Christina Cogdell: “Popular Eugenics: National Efficiency And American Mass Culture in the 1930s.“