The Cologne Progressives

Some years ago, while visiting the German city of Cologne, I discovered the works of the Cologne Progressive Artists Group (Gruppe Progressiver Künstler Köln), a bloc of artists that represented the radical outer fringe of the Expressionist movement of the Weimar Republic (1918-1933). Fortunately for enthusiasts of art from the Weimar years the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, Germany, has mounted an exhibition titled Progressive Cologne: 1920-33, Seiwert – Hoerle – Arntz. Running from March 15 to June 15, 2008, the exhibit is accompanied by a richly illustrated catalog book, Painting as a Weapon – a definitive text on the Progressives that is sure to please both historians and aficionados of German Expressionism.

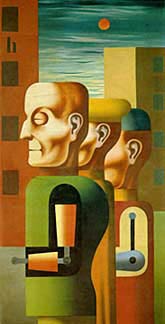

The exhibition focuses on three core members of the Cologne Progressives, Franz Wilhelm Seiwert, Heinrich Hoerle, and Gerd Arntz, with the exhibit presenting over fifty paintings and ninety prints by the artists. The Progressives were interested in the creation of a formal proletarian aesthetic, an innovative art of and for the working class. While the Cologne Progressives were in part inspired by the Soviet Constructivists, they did not adopt the severe geometric abstractions of their Soviet counterparts. Stirred by the aesthetics of “primitive” tribal art and the iconography of early Christian images, the Progressives never fully abandoned figurative realism. Instead they stripped what they perceived to be superfluous details from their paintings, prints and drawings, de-emphasizing individual features of the people in their artworks, leaving the minimalist figures to convey some instructive narrative. From 1929 to 1933, the group published a theoretical journal titled A bis Z (A to Z), where the writings and artworks of Progressive circle members and their associates were published.

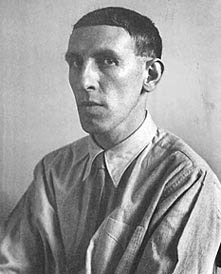

The photographer August Sander was attracted to the Progressive circle, aligning himself with the group in the early 1920s. His photos were often published in A bis Z, and his method of photographing his subjects according to their place in society’s hierarchy – revealing social tensions and class relations – was in harmony with the Progressive’s political and aesthetic outlook. Sander ended up photographing most members of the Progressive group, as with this portrait of painter Gottfried Brockmann now in the collection of the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Interestingly enough, at the time of this writing, the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles is presenting August Sander: People of the Twentieth Century – a selection of 130 photos taken by Sander during the Weimar years, an exhibit that runs until September 14, 2008.

The Progressives held two major views that set them apart from the larger Expressionist school. They rejected the notion of art in service to politics; only because they viewed the type of art they were creating as political action in and of itself – from their perspective their art was the revolution, or at least a vital component of it. Secondly, they commonly depicted people as generic symbols. By reducing and standardizing the human form, and by dressing their minimalist figures in garments worn either by oligarchs or workers, the Progressives intended to show how class divisions were imposed upon humanity. One of the Progressives who excelled in this type of didactic minimalism was Gerd Arntz, whose works would come to influence international design to this very day.

Gerd Arntz collaborated with the Marxist Viennese social scientist Otto Neurath on creating what they called the International System of Typographic Picture Education, or Isotype. The idea was to provide the working class with a universal visual language of symbols and pictograms that would assist them in understanding complex ideas concerning politics, economics, industry, and society in general. Neurath hired Arntz as a designer for the Isotype project in 1928, and over the years the artist designed some 4000 pictograms. While Isotype was based upon a radical political vision, the very concept for the pictographic road signs and other governmental pictograms we see everywhere today can be traced back directly to the collaborative work of Neurath and Arntz.

The Progressive’s drive to develop a new visual language was cut short by the rise of the Nazis, who branded them as “degenerate” and prohibited them from producing or exhibiting their works. Franz W. Seiwert died in Cologne in 1933 of radiation burns he suffered as a child – just before the Nazis undoubtedly would have come for him. Gerd Arntz was forced into exile in 1934 as Nazi repression against the arts increased, fleeing to the Netherlands where he would live and work until he died in 1988. In 1936 Heinrich Hoerle died in Cologne of tuberculosis, which had previously killed his father, sister, and first wife, Angelika. August Sanders never left Germany. In 1936 the Nazis seized and destroyed the printing plates for his photo book, Face of our Time, forbidding him to exhibit or publish. When his Cologne studio was destroyed in a 1944 Allied Forces bombing raid, thousands of his negatives were obliterated. Sander died in Cologne in 1964. Today, 4,500 original prints and some 11,000 original glass negatives are housed in the August Sander Archive in Cologne, Germany, the largest collection of his work in the world.