John Heartfield at the Getty

I wrote the following review in 2006 after seeing the exhibit Agitated Images: John Heartfield and German Photomontage, at the Getty Center in Los Angeles, California. That LA artists have not made a bigger deal over the exhibition of works by John Heartfield currently at the Getty Museum, is a perfect example of the cool indifference and political disengagement plaguing the artistic community.

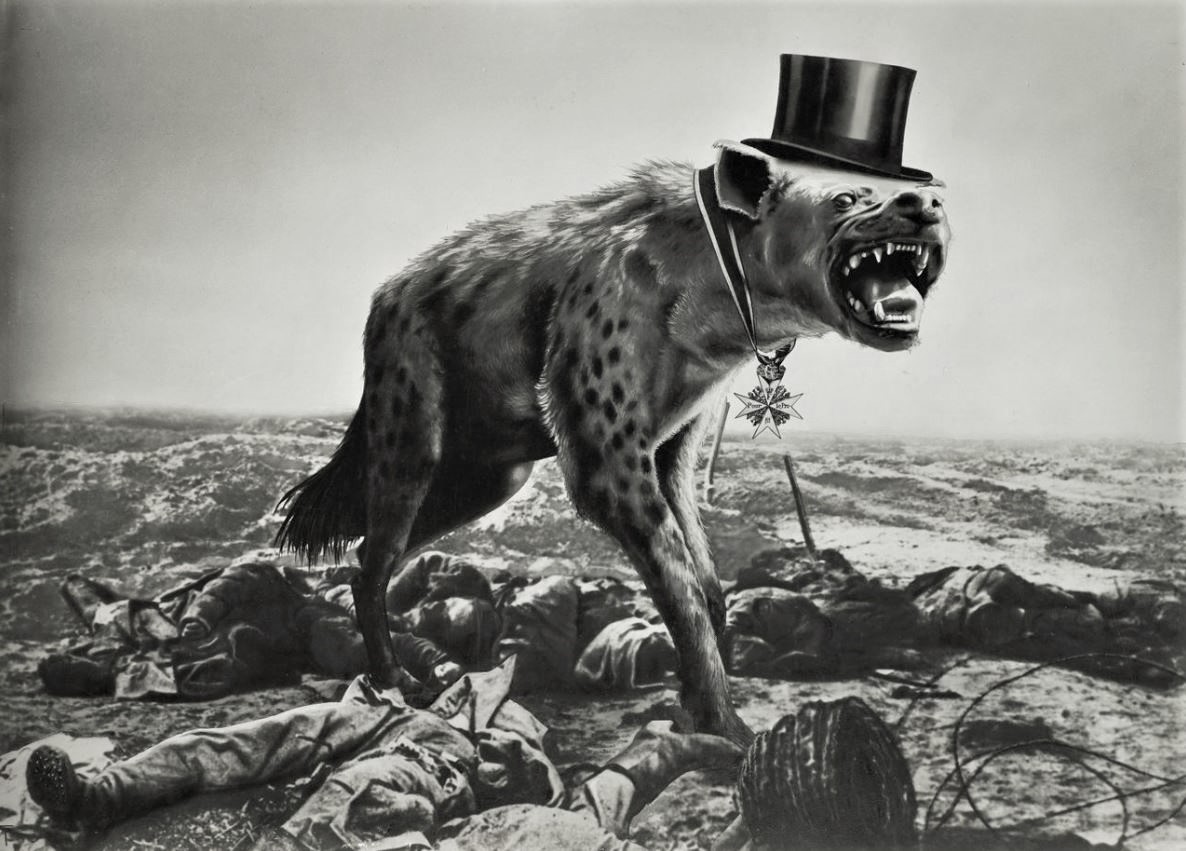

Few artists from the past have as much resonance in these troubling times, and Heartfield’s brilliant images continue to speak with a clarity of mind possessed when first produced, which was during the rise of fascism in Germany. Agitated Images: John Heartfield and German Photomontage, is one of the most important exhibitions recently mounted in Los Angeles; it not only illuminates the past, it points a way to the future for artists who want to address real world issues through their art.

Heartfield was a militant anti-fascist and a communist, but his artwork was also revolutionary when it came to technique and aesthetics.

He was one of the very first to explore photomontage as a new means of artistic expression, and some of his sparing designs, stripped down to only a few iconic images combined with text, made him the predecessor of today’s minimalist and postmodernist artists. Aficionados and students of contemporary art would do well to study the life and works of the great German master.

If you are not able to view the Getty exhibit, the next best thing would be to acquire the comprehensive book, John Heartfield: AIZ/VI 1930-38, a magnificent collection of the hundreds of works he created for the leftist magazine, Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung (Workers Illustrated News), also known as AIZ.

Leah Ollman wrote an article for the Los Angeles Times on the Heartfield exhibit that appeared in the paper’s Calendar section on March 6, 2006. Ollman’s generally positive review was titled Blinding sarcasm, but Heartfield’s work was anything but blinding, rather, he gifted the people a lucid vision.

Accompanying Ollman’s review was a reproduction of Heartfield’s trenchant Whoever Reads Bourgeois Newspapers Becomes Blind and Deaf, a word of warning never truer than today. How ironic that the LA Times placed Heartfield’s illustration next to the headline Ghostly Gowns, Dreamy Dresses, a heading about Paris Fashion Week… blind and deaf indeed.

I first discovered Heartfield’s work when I was only 16-years-old, and to say his art had a profound impact upon me would be an understatement.

Save for the nihilistic works produced by Germany’s dadaists, I had never before seen anything like Heartfield’s photomontages. If dada was the shell shocked babbling of artists confronting the unmitigated horror of modern warfare and a world gone insane, Heartfield’s art was the counterbalance; a precision surgical tool that would identify and cut at the causes of war and fascism. To my young eyes, some of Heartfield’s images were quite easy to understand, but others held their meaning from me since they dealt with unfamiliar events and individuals. Being inquisitive, I eventually peeled back those layers of history, and marveled at how honestly and directly the artist delivered his message. One can only imagine the deep impact his images had upon the German people in the 1930s.

To understand just how radical a democratic stance the artist took, one must begin with his name. In 1916, to protest against the anti-foreigner and anti-British hysteria promulgated by German ultra-nationalists, the artist changed his name from Helmut Herzfeld to John Heartfield, which was an extremely “unpatriotic” thing to do at the time.

Needless to say, Heartfield’s courageous stance made him a high profile target, and his unrelenting lampooning of the madmen who seized control of his homeland caused them to seek his death. He escaped their clutches of the fascists by going into exile, but never ceased creating the artworks that so infuriated them. Heartfield eventually returned to his country in 1950, where he died in 1968.

Agitated Images: John Heartfield and German Photomontage runs from February 21 until June 25, 2006. You can read more about the Heartfield exhibit at the Getty website.

______________________________________

UPDATE:

I also suggest reading John Heartfield: Laughter is a Devastating Weapon, by author David King and Ernst Volland. Artist, photographer, and historian, King was also an avid collector of Soviet Art and ephemera. His collection of some 250,000 Soviet posters and other historic collectables is now housed in the Tate Museum. King died on May 11, 2016 at the age of 73.