Paul Fuhrmann’s “War Profiteer”

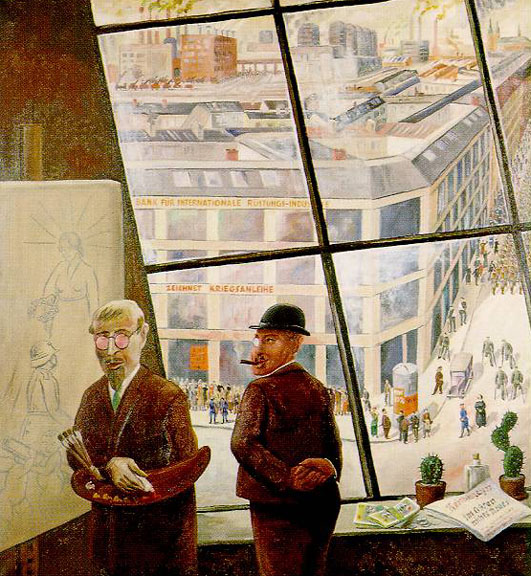

Paul Fuhrmann’s painting titled War Profiteer depicts a straightforward scene of an artist at work in his studio with a patron approvingly overseeing the beginnings of a freshly painted canvas. Upon closer inspection the picture reveals a narrative on the subject of culpability and corruption; the canvas is in actuality a fully relevant morality tale for today’s art world. Fuhrmann is little known outside of Germany, though he was an important figure in the avant-garde of that country during the pre-Nazi Weimar years (1919-1932). Though Kriegsgewinnler (“War Profiteer”) was painted in 1932 under extreme circumstances, it is still worth analyzing for the insights it continues to provide.

One can begin to unravel the painting’s message by taking note of what is shown outside of the artist’s garret. In the background great factories involved in war production belch smoke into the sky, with a bank building in the foreground proudly advertising war loans. The broad streets are filled with maimed war veterans on crutches and newly recruited marching soldiers, it is an ominous scene that not only indicates a nation engaged in endless warfare, but a social order where all aspects of society are intrinsically connected to militarism.

The political drama of the artwork focuses on the two figures in the foreground, an artist at his easel and his “War Profiteer” benefactor, a bowler hat wearing patron that one can assume is associated with either the arms manufacturing or banking industry. The well heeled client has just placed a somewhat large pile of money on the window ledge of the artist’s studio. The artist, preparing to work further on his painting, squeezes oil paint from a tube onto his wooden palette. He has already outlined the central figures of his canvas; a battle dressed soldier that pledges loyalty to the nation – represented by a woman with a radiating halo. Cherubs bearing an artillery piece complete the scene. Obviously the artist was not inspired by the muses, but by a desire to ingratiate himself with the rich and powerful elite circles running society. Appropriately enough, the artist painting the jingoistic tableau wears rose colored glasses.

Fuhrmann also included subliminal icons into his disquieting expressionist masterwork. While many German artists at the time included cactus in their modernist still life paintings, Fuhrmann seemed to include two of the prickly succulent plants as a sign of looming danger. What’s more, the metal frame that holds the studio window glass together first appears as a giant Christian cross, on second-glance it becomes a Swastika; symbolic of the sacred being obliterated by the profane and prescient of the liquidation of all those who opposed militarism on religious and political grounds. There was more than a little antiwar sentiment discernable in the painting, which made it anathema to right-wing nationalists. In 1933, the year after Fuhrmann painted War Profiteer, Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party seized absolute power in Germany; Fuhrmann and likeminded artists would pay a heavy price for their vision and outspokenness.

As with most of the German Expressionists, Fuhrmann’s anti-militarist stance did not simply come about overnight, it was based upon observance of and involvement in social reality, that and a mindfulness concerning the class dynamics of society. Born in Berlin in 1893, Fuhrmann was an art student at the Academy of the Museum of Applied Arts in Berlin under the Czech artist, Emil Orlik (1870-1932). Orlik’s students included George Grosz, who was to become famous for paintings and graphics that savaged the German ruling class of the period.

The First World War broke out in 1914, and the next year German authorities arrested Fuhrmann for his outspoken anti-militarist politics; WWI would end with at least five million civilians and some nine million soldiers killed. When the war ended in 1918, Germans overthrew the Kaiser at the beginning of the 1918-23 revolution, and Fuhrmann joined those revolutionaries who sought to create a popular, democratic government – the Weimar Republic. He participated in the street battles that broke out between right-wing followers of the old regime, and supporters of the new republic.

In 1918 Fuhrmann become a member of the Novembergruppe (November Group), those artists who believed that art must play a role in building a new progressive society. Members of the group included Max Pechstein, Otto Dix, George Grosz, Conrad Felixmüller, Hannah Höch, Wassily Kandinsky, Rudolf Schlichter, and many other notable expressionist artists. During the 1920s Fuhrmann began to explore the possibilities of collage and assembly artworks, and he began to regularly exhibit in galleries. Sometime around 1924 he joined the Rote Gruppe (Red Group), a radical artist’s association chaired by George Grosz.

From 1926 to 1927 Fuhrmann contributed many designs and illustrations to Germany’s growing left-wing and communist press. In 1927 he joined the KPD (Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, Communist Party of Germany), and in 1928 he joined the Association Revolutionärer Bildender Künstler Deutschlands (the “German Association of Revolutionary Artists”, co-founded by George Grosz). By 1931 right-wing violence and repression was well on the rise. That year Fuhrmann’s mixed media collage The Political Ones, an artwork denouncing the German court system of the day for its suppression of left-wing activists, was removed from a Berlin art exhibition by the police. The next year Fuhrmann painted War Profiteer.

When the Nazis assumed power in 1933 they immediately moved against arts professionals who did not conform to fascist ideals. The first to be attacked were writers, and books deemed “anti-German” were reduced to ashes in the mass public book burnings of ’33. Artists, filmmakers, and musicians lost their jobs, had their works banned, were forced into exile, or were sent to death camps. Fuhrmann’s teacher from his student days, Emil Orlik, had died of a heart attack a year earlier, but 1933 marked the end of the Orlik family. Being Jewish they would all perish at the hands of the Nazis, save for a single aunt. George Grosz went into exile in the United States.

The Nazis listed Fuhrmann as a “degenerate artist”, and forbade him from doing his work. His artworks were banned and seized by Nazi authorities, who included War Profiteer in their infamous 1937 traveling exhibition, Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art).

The fascist authorities removed all avant-garde artworks from the nation’s museums – some 16,000 paintings, prints, drawings, and sculptures – using a selection of 650 of these artworks to create the Entartete Kunst show. The exhibit condemned modern art as “anti-German”, the product of mental illness and of “Jewish-Bolshevist” conspirators. Some 3 million people attended the show during its four-year tour of Germany. Inclusion in the exhibit put Fuhrmann in good company as paintings by the likes of Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, Max Ernst, Paul Klee, Marc Chagall, George Grosz, and many other exemplary artists were also placed in the mocking display.

The artworks in the exhibit were divided into subgroups, nine in all, each presenting supposed characteristics in art the Nazis found anathema to their extreme rightist philosophy. Artworks were condemned for their “barbarous” ultramodern aesthetics, for their “shameless mockery of any religious idea”, for promoting “Marxist and Bolshevik ideology” and for idealizing “the negro as the racial ideal” in modern art – along with “the idiot, the cretin, and the cripple.” One set of artworks was meant to showcase the “Revelation of the Jewish racial soul”. Groups of artworks were surrounded by hostile slogans daubed onto museum walls; “An insult to the German heroes of the Great War”, “Crazy at any price”, “Madness becomes method”, “The cultural Bolsheviks’ order of battle”, and “Jewish, all too Jewish”. One grouping had to do with art construed as “sabotage of national defense”, Paul Fuhrmann’s War Profiteer was likely placed with those paintings. Quoting the original Exhibition Guide printed by the Nazis on the nature of that particular group of artworks:

“Here ‘art’ enters the service of Marxist draft-dodging propaganda. The intention is manifest: the viewer is meant to see the soldier either as a murderer or a victim, senselessly immolated for something known to the Bolshevik class struggle as ‘the capitalist world order.’ Above all, the people are to be deprived of their profound reverence for all military virtues, valor, fortitude, and readiness for combat. And so, in the drawings in this section, alongside caricatures of war cripples expressly designed to arouse repulsion and views of mass graves delineated with every refinement of detail, we see German soldiers represented as simpletons, vile erotic wastrels, and drunkards. That not just Jews but ‘artists’ of German blood could produce such botched and contemptible works, in which they gratuitously reaffirmed our enemies’ war atrocity propaganda – already unmasked at the time as a tissue of lies – will forever remain a blot on the history of German culture.”

Paul Fuhrmann survived the Nazis as well as the bombings of Berlin by the Allied powers, but he never abandoned the city throughout all of the violence and destruction it suffered. He would pass away in East Berlin on January 25, 1952.

On a side note, long before the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), became an appendage of the BP corporate empire, it organized a partial reconstruction of the infamous exhibition in 1991, intended to reveal the crimes against art committed by German fascism. Curated by Stephanie Barron and titled “Degenerate Art”: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany, the exhibit traveled to the Art Institute of Chicago later that same year.

The show displayed 150 surviving artworks as well as archival materials like motion-picture footage and photographs. Having walked through the L.A. exhibit during its opening week, I still regard it as one of the most impressive shows LACMA ever mounted.

In collaboration with the Harry N. Abrams publishing house, LACMA also produced an exhaustive exhibit catalogue full of incisive essays and historic photos – as well as a listing (with biographies) of many of the artists whose works were included in some of the original Entartete Kunst exhibits. The inside cover of the catalogue stated unequivocally that the book’s essays “cannot help but suggest a parallel with our own times, in which artistic freedom is under attack by ideologues.” Fortunately LACMA has made a .pdf version of the entire catalogue that is currently available online. In the forward to the 1991 catalogue, then Director of LACMA, Earl A. Powell III and James N. Wood, Director of the Art Institute of Chicago, wrote the following:

“Our exhibition and catalogue ‘Degenerate Art’: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany examines the events surrounding that condemnation of modern art. Although this project has been in the planning stage for five years, its topic has recently attained greater timeliness. Museums in this country have relied for a quarter of a century on government grants through the agencies of the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities, and the Institute for Museum Services. This assistance has, among many other things, enabled public institutions to continue to present important exhibitions to an ever-growing public and to attract private and corporate funding. As the 1990s begin, museum exhibitions are in a precarious position. If government support for the arts is jeopardized, the ability of all museums to organize exhibitions will be affected and the museum as an educational institution will be seriously diminished.

Only with two very generous subventions from the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities have we been able to mount this exhibition, organize its related events, and produce this catalogue. This exhibition focuses on events that are powerful, disturbing, and sometimes difficult to understand. It is especially gratifying to us that the Endowments recognize the importance of the issues and made it possible for us to pursue the project.”

It must be noted that the government arts agencies Mr. Powell and Mr. Wood regarded as absolutely vital to the mounting of LACMA’s Degenerate Art exhibit, have had their budgets whittled away over the years. At the time of the 1991 exhibit the budget for the National Endowment for the Arts was $174,080,737 – adjusted for inflation that would be $275,103,014 in today’s dollars. President Obama’s proposed NEA budget for fiscal year 2012 is a trifling $146,255,000.

What is more, museums have been increasingly moving away from being institutions that acquire, care for, study, and exhibit objects of enduring significance, and are instead being steadily transformed into entertainment centers; venues where “blockbuster” shows curated or sponsored by corporate entities pander to popular tastes. LACMA has gone that route, which is why it is hard to imagine the museum ever again mounting an exhibit as profound as “Degenerate Art”: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany.

A case in point, from May 29 to October 31, 2011, LACMA is presenting a “major retrospective” on the works of Tim Burton. According to LACMA the exhibit examines “the full range of Tim Burton’s creative work, both as a film director and as an artist.” The public will have the dubious honor of viewing storyboards, puppets, movie related concept artworks and illustrations, as well as other bits of cinematic ephemera from Burton films like Mars Attacks! and Edward Scissorhands. Museum goers will also have the opportunity to view screenings of Burton’s films at LACMA’s Bing Theater, cinematic masterworks like Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure (1985), Batman (1989), and the pointless 2001 remake of Planet of the Apes.

Why those in charge of LACMA regard Burton’s works as the pinnacle of artistic achievement is anyone’s guess. In all fairness, the exhibit was actually organized and curated by New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), and funded by SyFy, the U.S. cable television channel owned by entertainment conglomerate, NBCUniversal. During its five-month run at MoMA, 810,500 visitors took in the show, making it the third-highest attended exhibit in the museum’s history. At $20 dollars per ticket MoMA brought in $16,210,000 with its Tim Burton extravaganza, no doubt LACMA hopes to do the same. Perhaps LACMA will next mount a major retrospective featuring ephemera from the career of late pop star Michael Jackson.

But back to Paul Fuhrmann and his brilliantly critical painting, War Profiteer.

While Fuhrmann confronted untenable circumstances that were far removed from our own, every epoch offers conditions and events that demand responses from artists, yet little of social reality seems to register with artists at this point in time. The issues are indisputably daunting; the crisis of modernity, the vulgarity and crassness of late capitalism’s hyper-consumerist societies, the deterioration of democracy and the ascendancy of oligarchy, our collective lurching towards worldwide environmental catastrophe. These are undeniably difficult concerns for artists to grapple with, but as was the case with Fuhrmann and his fellow German Expressionists, a way was found to assail social backwardness and the systematic destruction of culture beneath the weight of capital and the heels of hobnailed boots.

The type of artist portrayed in Paul Fuhrmann’s War Profiteer is with us today, though perhaps in far larger numbers and with a greater capacity for self-delusion. Metaphorically speaking, the most notable aspect of today’s art scene, from top to bottom, is the fashionable wearing of rose colored glasses. Fuhrmann’s admonition to the artist is more pertinent than ever.