Nepotism & Scatological Postmodernisms

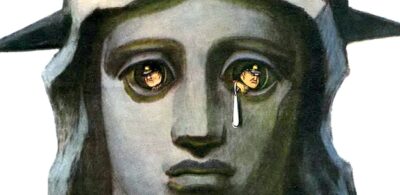

Trouble is brewing in the realm of the postmodern art world, one of its stars could take a big fall, and with any luck his plummet may indicate the entire postmodernist school could soon topple. Chris Ofili, the artist famous for incorporating elephant dung into his portrait of the Virgin Mary, is at the center of the controversy, which an arts correspondent for the U.K. Telegraph put this way, “Chris Ofili said artists should give work to the Tate for nothing… so why has he accepted £100,000 for one of his dung pictures?”

In October of 2004, Ofili wrote an article titled, Donations gratefully received, which was published in the UK Guardian. Ofili’s piece was an appeal to contemporary artists of note to donate their works to the Tate Modern museum in London. Dressing himself in a benevolent persona, Ofili pitched the idea that artists should give their works of art to the Tate… free of charge, because it would be “an altogether positive thing to do.”

A number of big name artists responded to the Tate request for donations of major works, including David Hockney and Lucian Freud. But then a bolt from the blue revealed this jubilant scene as a seedy fiction.

In July of 2005, The Tate announced the acquisition of Ofili’s The Upper Room, and while the museum refuses to say how much they spent, word has it the cost of the acquisition was upwards of £100,000 ($180,699). So while begging with hat in hand, pleading a lack of funds for new acquisitions, and accepting donated artworks into its permanent collection, the Tate Modern somehow managed to scrape together the necessary funds to purchase an artwork from one of its own trustees—yes, Ofili is a trustee of the Tate.

In the official press release heralding the purchase, the Tate failed to mention Ofili as a trustee – I believe the word for this arrangement is nepotism. The Stuckists of London, always ready to enter a fracas if it means getting a chance to thrash postmodernism, have released a statement through their co-founder, Charles Thomson.

“We believe this is an unacceptable state of affairs. In fact it’s outrageous. For the gallery to buy a work from someone who sits on its governing body smacks of cronyism. Our feeling is that if this sort of thing had happened in the world of business there would be an almighty stink. It is particularly galling that the Tate bought the work at a time when it is urging other people to hand over their work for nothing. It does not matter if the work costs a fiver or £5 million – the point is that Ofili should have donated it.”

Just what enticed the Tate to conduct such a shady transaction, what masterwork was worth throwing all caution to the winds for? The Tate boasts that the new Ofili acquisition is a “landmark work”. A museum spokesman said that “to neglect to acquire this major group of paintings would represent a missed opportunity.”

Comprised of 13 separate paintings on canvas, Ofili’s piece has a religious theme—but one would be hard pressed to place it in the tradition of sacred art.

The title of Upper Room refers to the second floor of the inn where the last supper was held, and Ofili doesn’t disappoint his devotees when it comes to his trademark use of elephant dung in his paintings.

Don’t cringe just yet dear reader, you haven’t read the best of it. Ofili depicts Christ and his disciples as rhesus monkeys—with Christ of course being the biggest monkey.

Each simian figure wears a little turban and jacket and holds a goblet in one hand—with a lump of excrement placed above the chalice. Instead of being hung properly in the museum, each painting sits on two balls of elephant dung to lean against the wall.

While I was born into a Catholic family, I’m not religious by any stretch of the imagination, but you’d be wrong to think I find amusement in Ofili’s scatological paintings. If the artist had so treated the Jewish or Islamic faith, you can take for granted his artworks would not be hanging in a museum.

However, it’s not my intention to enter a discussion over the existence of God or to argue over whose God is the biggest. I’ll leave that to the theologians and true believers. It is enough for me to say that I find Chris Ofili’s attacks upon the faithful exceedingly cruel, malicious, and designed to bring the greatest amount of attention to himself.

That he is a talentless hack completely devoid of skill and vision should go without saying, but to rebuke Ofili is also to admonish the very institution he serves as a trustee.

The greater crime here is the sleazy favoritism displayed by a museum towards one of its own trustees. Ofili should resign without delay, and if the Tate had any interest in retaining its credibility as a major art institution, they’d insist upon his resignation.