Street Art & The Splasher Manifesto

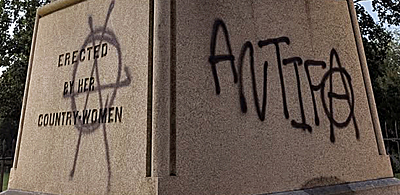

During the last few months in New York City, someone has taken to destroying the illicit stencil graffiti art and wheat-pasted posters of that city by splashing them with brightly colored daubs of paint. Nicknamed “the Splasher” by the media, the perpetrator has for the most part ignored the majority of street art, preferring instead to purposefully target and deface works by “big name” street artists – the art of Shepard Fairey being a high value target for the vandal.

Now “the Splasher” has been revealed to be a collective of sorts, with a profusely illustrated 16-page manifesto taking credit for the vandalism being delivered to the offices of Gothamist.com. Many have come forward to condemn the Splasher group for wanton destruction of street art, which to me is an amusing contradiction – how can vandalism be vandalized?

Initially I was disinclined to write about this whole silly affair, but an essay in the New York Times sent me over the edge. First, let it be known that I’m a supporter of street art, and have dabbled in it myself.

I feel that its methods, even though largely prohibited, can be perfectly appropriate – if the result is the circumvention of the elite art world with the intent of introducing art into everyday life, an oppositional “art for the people” if you will.

However, when it comes to “being with the people” there’s a big difference between political practice and facile rhetoric. I realize that what I’m about to say may be construed as politically incorrect by those who exalt and defend street art, but I’m bemused by this faux controversy.

Sometimes I feel a bit like Winston Smith, the lead character in George Orwell’s haunting dystopic novel, 1984. In one memorable chapter from that book, Smith stumbles into a shabby antique shop and discovers a glass paperweight. The delicate ornament has no value in the harsh social order Smith is a part of, it is an utterly useless thing disdained by the authoritarians who run society and forgotten by everyone else. The object’s sheer loveliness makes it a dangerous and subversive thing. Smith falls in love with the glass orb, realizing that it represents something banished from his reality… beauty.

Now beauty is found in many things, and indeed it can be discovered on the surface of wheat-pasted graphics posted on grimy city streets. But I’m not about to trade my elegant glass paperweight for a tattered grimy old poster. If we are to defend art, yes, there are battles to be fought on the avenues, but shouldn’t we also aim higher?

Street art by its very nature is implicitly political, whether it’s done for aesthetic reasons or not. It conveys a social message in that it redefines public space as delineated by the law. Some street art transforms cheerless urban squalor into colorful outdoor art galleries and gives voice to those who cannot pay inordinate amounts of money to have their ideas “legally” presented to the multitudes. But let’s be clear and direct, there are those who participate in street art because they have a social vision, and those who participate because it offers an opportunistic fast track to fame and fortune.

By breaking the sanctified laws of private property, street art has been classified as “vandalism,” however, let’s be honest… who wants their property vandalized?

In some quarters having an outlaw reputation no doubt comes in handy, and such swaggering “street cred” allows one to huff and puff a great deal, so there’s no mystery as to why elite art circles, enamored of the bizarre and always in search of the “next big thing,” have embraced such gimmickry.

In our media saturated society it’s a given that an individual with the resolve to blanket a city’s walls with their tedious street art posters, and then follow up with a series of showy press conferences and gallery exhibits – will become the focus of a media feeding frenzy.

While lucrative careers have blossomed in this manner, exactly how have the arts been advanced? Thousands of serious and dedicated artists whose marvelous works deserve acknowledgement go ignored as the media is mesmerized by the shenanigans of a gaggle of art stars. There is more than a ring of truth to the Splasher Manifesto, when it states: “The present and banal methods of confronting the prevailing social order through street art have become rotten and rigidified into methods of commodification.”

There are finer points to discuss, like why untold numbers of hideous corporate sponsored billboards despoiling a community are considered legal, while a single unauthorized and non-commercial street poster or graffiti is considered criminal. But to squabble about minutiae takes us from the subject at hand. Street art is ephemeral and was never meant to be long lasting, its romantic and poetic resonance can be found in its transient quality – like those realistic chalk pastel drawings we’ve all seen done on sidewalks. It can also be said that some street artists routinely destroy the works of other street artists.

The most celebrated graffiti, stencil art, and wheat-pasted posters are only the top most layer of artworks buried in the fierce competition to be seen and recognized. In that sense, street art is more the counterpart of the cutthroat advertising ethic than a heartfelt gesture of human solidarity.

Most street art was long ago co-opted by the elite art world, and the example of Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring in the 1980’s should be proof enough of that. Without question, this is the other aspect to the street art chronicles that I find particularly obnoxious. While I appreciate some street art for its whimsy, boldness and occasional insights, I don’t think it can in any way be equated to the higher arts. While I’m an advocate of a multiplicity of styles, I believe that the wholesale espousal of street art aesthetics has lead to a debilitated capacity to discern quality and profundity. We have in essence traded in the talented and disciplined muralists of old for pranksters who wheat-paste self-promoting pabulum onto our city walls.

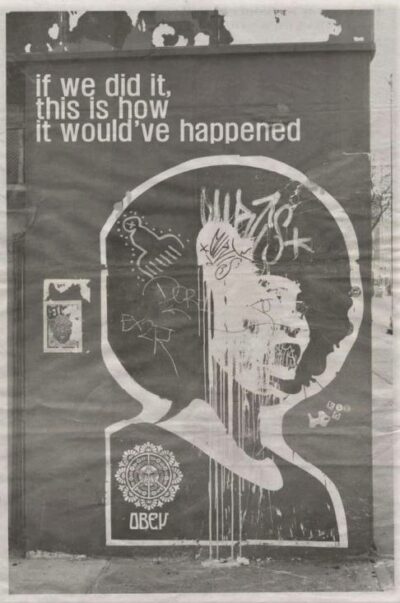

I’ve never understood how Shepard Fairey’s minimalist and obscurest street art portraits of the late wrestling champion, Andre the Giant, have come to be interpreted as meaningful and profound art – Fairey’s statements notwithstanding. He has said his Obey Giant posters “stimulate curiosity and bring people to question both the campaign and their relationship with their surroundings, because people are not used to seeing advertisements or propaganda for which the motive is not obvious.”

That statement seems little more than self-serving claptrap to me, giving some credence to the Splasher’s attacks upon “a cultural realm which revealed a content of commodity recuperation behind the façade of pseudo opposition.” That is especially so now that Fairey’s artworks display $40,000 price tags. I’m not opposed to an artist making money, goodness knows I’m trying to do that myself, I do after all enjoy food on my table and a roof over my head. But there is a difference between having a career and being a careerist. Page thirteen of the Splasher Manifesto puts it all in focus:

“There are those who have begun rejoicing over graffiti’s inevitable deterioration out of the realm of criminality and into the world of legitimacy, petrification, and those festering institutions so well respected within the culture vulture circles. And as always stripping every last piece of warm flesh to the bone, so it continues with the Brooklyn Museum’s recent exhibition of regurgitated vandalism gone mad with territoriality, individualism, and technique. And of course a degree in the fine arts never hurts does it? So let the floodgates of dissertations and resumes open with their doctorates already in hand!”

In the essay that set off this tirade, Splashing the Art World With Anger and Questions, New York Times art critic Michael Kimmelman makes a few salutary points. He correctly observes that the Splasher group takes inspiration in part, from the Situationists of the late 50’s and early 60’s. An incredibly prescient group of trouble making artists and intellectuals, the Situationists have been credited with giving rise to everything from performance art to punk rock – and my own aesthetic vision has in no small way been impacted by Situationist theory.

Kimmelman gives the political philosophy a brief but fair reading, noting that “by comparison” with the Splasher group, “Situationist pranks were pointedly political,” and that “across nearly half a century of random art world mischief, they seem almost scientific in their focus.”

However, Michael Kimmelman rightly questions the Splasher group’s lack of clarity by stating: “the current agitators, although they’ve got some of the revolutionary patter down, seem to lack clearly defined targets or priorities. Is the problem gentrification or the art market or artists or late capitalism? What’s troubling them – the street art they’re defacing or the fact that some of the street artists might also show in galleries?” But the actual thoughts that prompted me to write this harangue, were the final remarks from Kimmelman’s essay, words to which I wholeheartedly agree:

“All that said, public space and civic justice are difficult issues to which the brouhaha returns our attention. New York neighborhoods are indeed changing, not all for the better, as the city becomes more affluent and homogeneous, and art shouldn’t exist in it simply as a symbol of wealth and privilege. It should seize public spaces where it can, to make itself more part of daily life, more relevant in the world, and to become a source of serendipity, pleasure, trouble, controversy and interest to people outside the art world, not just inside it. (….) this latest little flap is proof that art can still matter.”

The New York Times has republished the entire Splasher Manifesto in .pdf format. View, download and print the 16 page illustrated screed from the NYT’s website.