Spencer Jon Helfen: California Modernist Painting

Spencer Jon Helfen Fine Arts is tucked away on the second floor of a charming old building in Beverly Hills, and though most of those living in the city of Los Angeles have never heard of the gallery – it is one of L.A.’s treasures. The founder and director of the enterprise, Spencer Jon Helfen, has a passion for Modernist art of the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s – and his gallery specializes in the California School of Modernism that flourished in the state prior to World War II. Helfen’s gallery is an oasis of sorts, a setting where one can contemplate the thought-provoking and beautifully crafted figurative realist paintings that were once so highly regarded by the art world. The Helfen is one of the few galleries in the U.S. to consistently mount large-scale exhibits of California modernist paintings on a regular basis.

I attended the public reception for the Helfen’s current exhibition, Gallery Selections of Important California Modernist Paintings & Sculpture, which presents the Helfen’s latest acquisitions of works from the likes of Mabel Alvarez, Victor Arnautoff, Claude Buck, Francis De Erdely, John Mottram, Koichi Nomiyama, Helen Clark Oldfield, Otis Oldfield, Edouard Vysekal, Bernard Zakheim, and many others. Students and aficionados of figurative realist painting would do well to carefully examine the lives and works of each and every artist in the show, in addition to working at cultivating a deeper understanding of the early California Modernist school. I have an especially strong interest in that movement, not because I am a native born Californian, but for the reason that the school was disposed towards social engagement in art.

In this article I will focus upon two of the forgotten giants of the California Modernist movement included in the Helfen exhibit – Victor Arnautoff and Francis De Erdely. Exemplars of figurative realism, craft, and humanist concerns in art, Arnautoff and De Erdely are ripe for rediscovery, especially by those who seek an alternative to the vortex of today’s postmodern art follies.

Arnautoff’s oil paintings at the Spencer Jon Helfen Gallery, are lavish in detail, stunningly rich in color, and filled with texture – they are jewel-like works of social realism created by a technical virtuoso who possessed complete mastery over his materials. Arnautoff had a great talent for capturing, not just the likeness of a person, but something of their essence, and for me two of his portraits in the show form a focal point of the exhibit. His Woman in Yellow Fur is a stunning close-up portrayal of a young woman who, one must assume, is well-to-do, since she is draped in fur and the date of the portrait, 1934, places her right in the middle of the Great Depression. Her fancy attire notwithstanding, there is a sympathetic air about the woman. Arnautoff’s brushstrokes are particularly forceful in this painting, which is unusual for him. He also incised the paint surface using the sharp end of his brush, brilliantly replicating the appearance of fur. His juxtaposition of the warm yellow ochres and burnt siennas of the figure against the backdrop of a cold and pale ultramarine blue, makes for one attention-grabbing portrait.

Similarly, Arnautoff’s The Green Dress, is also a stunning likeness, but in this work there is absolutely no ambiguity as to the class background of the sitter. The haughty imposing blond with a large strand of pearls around her neck is clearly bourgeois, and her confident, piercing gaze informs you that she is familiar with the wielding of power. A slightly raised eyebrow lets you know that you are being carefully evaluated, even across the barriers of space and time. Again, the light ochre background and warm flesh tones of the sitter juxtaposed against the brilliant cadmium green dress makes for a dramatic use of color. It is a marvelous painting, one that I could gaze upon endlessly. How could such a gifted artist be so easily forgotten and sidelined by the passage of time? Truth be told, Arnautoff was written out of history – for aesthetic and political reasons.

Victor Arnautoff (1896-1979) was born in Tsarist Russia and fought as a Cavalry Officer in the Tsarist Imperial Army, which I suppose would categorize him as a “White Russian”, or counter-revolutionary. Fearing persecution he fled the Soviet Union after the triumph of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, first going into exile in China where he would meet his future wife, and eventually making his way to Mexico, where he would undergo a remarkable transformation both artistically and politically. In the late 1920’s Arnautoff studied with and became an assistant to Diego Rivera in Mexico City, no doubt absorbing the master’s ideas regarding a resurgent muralist movement. Not since the Italian Renaissance had there been such a vital school of fresco mural painting as was to be found in Mexico during the 1930s. Rivera had studied the technique while traveling throughout Italy in 1920. Basically fresco involves painting on wet lime plaster with pigments mixed in water; once the moisture dries the color is fixed. Well-versed in the theory and practice of muralism, Arnautoff would make his real mark on the world when he came to settle in San Francisco, California, in the early 1930s.

Victor Arnautoff would help Diego Rivera paint two murals when the Mexican muralist first visited San Francisco from 1930-31; Allegory of California at the Pacific Stock Exchange, and Making of a Fresco located at the Art Institute of San Francisco. American artists in the San Francisco Bay area and beyond where electrified by Rivera’s murals and by the Mexican Muralist Movement in general, in which they perceived the possibilities of an equivalent muralist school for the United States. They would get their chance to initiate such a movement with the Coit Tower murals, which coincidentally were painted 75 years ago this month.

In 1933 Coit Tower was constructed atop Telegraph Hill as a city beautification project, immediately becoming a landmark attracting tourists. The Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), the first government program to employ artists as part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), set out to create a series of monumental fresco paintings on the tower’s interior walls in 1934. The PWAP appointed Victor Arnautoff technical director for the mural project, and twenty-six artists were selected to design various artworks on the theme of “Aspects of California Life.” Ten assistants also facilitated the work, doing everything from mixing pigments to grouting fresh plaster.

The production of the Coit Tower murals converged with two dramatic events that turned the project into a lightning rod for controversy. Diego Rivera’s mural at New York City’s Rockefeller Center, Man at the Crossroads, was destroyed by order of John D. Rockefeller on February 10, 1934, because one small part of the mural included a portrait of communist leader Vladimir Lenin. Many of the artists working on the Coit Tower murals had met Rivera, and were naturally against the destruction of his mural.

Victor Arnautoff and his fellow muralists also supported San Francisco’s longshoremen, seaman, waterfront workers, teamsters, and municipal workers – who went on strike against low wages, long hours and terrible working conditions on May 9, 1934. On July 5, 1934, in an effort to defeat the strike, employers used strike breakers with police escorts to move goods from piers to warehouses – riots ensued, with the police shooting dead two strikers on what came to be called Bloody Thursday. Up to 40,000 people held a funeral march for the slain workers, an event Arnautoff memorialized in a drawing unrelated to the Coit murals. In the aftermath of the lethal police repression, the entire city of San Francisco was shut down in a great General Strike which lasted three days – it was the biggest labor action in U.S. history.

Arnautoff and a number of the other artists working on the Coit Tower murals felt it necessary to comment on these events – and so included certain images in their murals. For instance, in his mural titled Library, artist Bernard Zakheim depicted a group of men gathered in the periodicals room of a library, reading newspapers whose headlines referred to the destruction of Rivera’s mural as well as to the San Francisco maritime strike. Zakheim included a portrait of fellow Coit Tower muralist, John Langley Howard, reaching for a shelved copy of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital. Zakheim also included a self-portrait in his mural, showing himself reading a copy of the Torah in Hebrew, with other sacred books in Hebrew close at hand. No doubt the rampant anti-Semitism of the period contributed as much to attacks on the mural project as did anti-communism.

The press became indignant over the small amount of left-wing imagery found in the murals, the San Francisco Chronicle branding them “red propaganda”. As right-wing outrage over the murals intensified, the PWAP almost give in to conservative pressure, slating Zakheim’s mural, and a number of others, for whitewashing. The opening of Coit Tower for public viewing of the murals was delayed for months, and fortunately the controversy subsided. When the Tower was finally opened to the public only one mural had actually been censored, Steelworker, a portrait of a tough looking laborer by Clifford Wight. The artist had incorporated the slogan “Workers of the World Unite” into the portrait’s background – PWAP had the slogan obliterated.

Victor Arnautoff’s contribution to the Coit Tower mural series is titled, City Life (Click here for a YouTube video of the mural), a vibrant depiction of street life in San Francisco during the 1930s. As with most of the other works in the tower, City Life was a fresco mural painted on wet lime plaster – and it displays all of the qualities of a fine mural painting done in that technique. As much as I venerate Arnautoff’s fresco murals – and he painted a number of them, it is his oil paintings that I am truly passionate about, and those on view at the Helfen gallery are superlative examples of the modernist master’s power.

That the very first WPA project put artists to work creating monumental murals at Coit Tower speaks volumes about where America is today as a nation. Almost no one, not even professionals in the arts community, can imagine a colossal public art project being mounted at the present time – yet in my opinion such a project is more than feasible.

I have to admit knowing next to nothing about Francis De Erdely prior to attending the opening at Spencer Jon Helfen Fine Arts, but what an introduction I received! I am eternally grateful to Mr. Helfen, not only for bringing the commanding works of De Erdely to my attention – but also for placing his works before the general public.

A centerpiece of the show, De Erdely’s Unjust Punishment is a modernist tour de force, a masterwork that alludes to all the world’s suffering – while still being an allegorical statement against McCarthyism, the anti-communist witch-hunts that swept the U.S. during the 1950s. The mixed media painting on illustration board depicts two crucified men, and the work has all the appearance of a stained glass window. While the painting is clearly figurative in nature, it freely incorporates aspects of cubism and abstraction, an approach De Erdely increasingly adopted in the later half of his life. That fact notwithstanding, De Erdely still ended up persona non grata in an art world that was to become wholly given to pure non-objective abstraction. I am left wondering if the broken men on their crosses in part serve as a metaphor for the realist artist abandoned for the sake of the “next big thing” in a fickle art world.

Francis De Erdely (1904-1959) was born in Hungary in 1904, and grew up during the ravages of the first World War. In the aftermath of that conflagration his country moved ever rightward, until a homegrown fascist movement developed that would eventually ally Hungary to Nazi Germany. As a young artist De Erdely was on a collision course with the Hungarian right for having depicted the atrocities of World War I in his paintings and sketches. He was also evidently supportive of the Spanish Republic and its struggle against fascism, creating sketches that revealed his sympathies but further provoked Hungary’s right-wing. Under pressure from Nazi Germany, Hungary joined the Axis powers in 1940, and De Erdely was apparently banished from his homeland during that period. Ultimately he would make his way to the United States, living for a short time in New York before finally making the city of Los Angeles his home in 1944. De Erdely became the dean of the Pasadena Art Institute School from 1944 to 1946, and he taught at the University of Southern California from 1945 until he passed away in 1959.

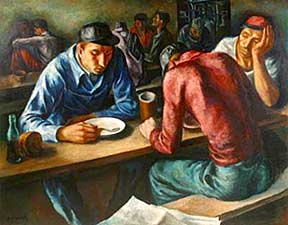

De Erdely’s early paintings were similar to Victor Arnautoff’s in that they were straightforward works of social observation. De Erdely was particularly fascinated with the underclass he discovered in Los Angeles, choosing them as his most consistently painted subject. He came to imbue his works with abstract sensibilities, but never abandoned his predilection for a humanist social realism. Daily Bread, his 1945 painting of a worker at rest, has an almost biblical quality about it, exemplifying the artist’s deep compassion for working people.

The works of Victor Arnautoff and Francis De Erdely make the Helfen show unusually rewarding, but then the entire exhibit is noteworthy. Arnautoff and De Erdely provide us with examples of a humanistic art at once accessible, anti-elitist, and given towards speaking clearly and directly to an audience. In all honesty, what I found so refreshing about the exhibit is that it gives insight into what figurative art was like before being contaminated by postmodernism. The paintings in the Helfen exhibit are devoid of irony, shock value, and vulgarity; they unabashedly pursue beauty and universality, and best of all – you do not need reams of mounted wall text to understand them. I am not at all saying that today’s artists should simply use the California Modernist school as a template to be replicated, but I do believe that a full understanding of and appreciation for California Modernism can serve as an important springboard for artists envisioning how art might advance into the 21st century.

Gallery Selections of Important California Modernist Paintings & Sculpture. Now running at Spencer Jon Helfen Fine Arts until March 28, 2009.