I Am Not The Enemy

I will never forget waking up on September 11, 2001 to the spectacle of the Twin Towers being hit by missile-like planes. That day I turned on morning television only to see those slow motion videos of doom and destruction; I watched with eyes full of tears and heart full of dread.

Nearly 3,000 people perished in the terror attack, but I felt there was something much worse yet to come.

In the immediate aftermath of the horrendous crimes committed on Sept. 11, thousands of racially motivated attacks took place in the U.S. that targeted anyone who “looked Arab.” Mosques were vandalized and firebombed. Arab-Americans, Muslims, and South Asians were harassed, beaten, and killed. As the attacks intensified, I responded by creating an artwork titled, I Am Not The Enemy, which was nothing more than a plea for sanity and religious tolerance. The political atmosphere at the time reminded me of another era, the days after the Japanese Empire attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii in 1941, and “patriotic” Americans unleashed their fury upon innocent Japanese-American citizens. President Roosevelt would issue Executive Order 9066, sending 120,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast to what the president himself called “concentration camps.”

Nine years after 9/11, 5,697 U.S. soldiers have been killed in Iraq and Afghanistan to this date, and President Obama has escalated the Afghan war. Untold numbers of Iraqi and Afghan civilians have perished, and Islamophobia in the U.S. has increased. A proposed Islamic cultural center in lower Manhattan has turned into a frenzied national campaign of hate against all things Islamic – and I fear a terrible violence will follow.

Accordingly, when I was informed that a candlelight vigil against hate crimes would be held at the Japanese American National Museum in downtown Los Angeles, I was eager to attend.

Nikkei for Civil Rights & Redress (NCRR) and the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), worked in cooperation with the Japanese American National Museum to organize the silent candlelight vigil; the objective was to express support for Muslim Americans and their constitutional rights, as well as to condemn religious intolerance.

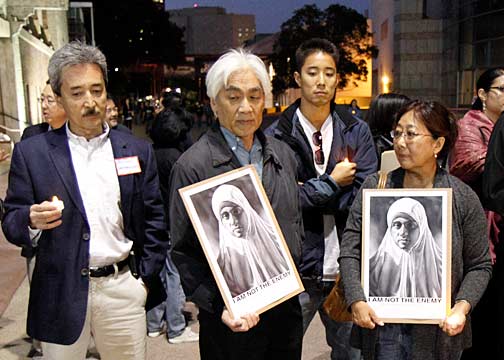

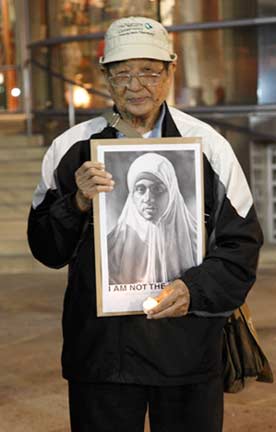

The vigil took place during the evening of September 9, 2010, and nearly 200 people, mostly Japanese Americans, gathered on the plaza in front of the museum. I distributed a few dozen copies of my I Am Not The Enemy poster to those assembled, and the prints were warmly received.

The public relations director of the Japanese American National Museum, Chris Komai, addressed the crowd, which was incredibly significant in and of itself. Most museums are aloof when it comes to real world issues and community affairs, and one does not ordinarily think of museum personnel taking part – officially or otherwise – in political protests of any kind.

I was unfortunately unable to hear Komai’s oration as I was busy taking the pictures you see in this article, however, I would like to point out that the Japanese American National Museum has the following in their mission statement; “We share the story of Japanese Americans because we honor our nation’s diversity. We believe in the importance of remembering our history to better guard against the prejudice that threatens liberty and equality in a democratic society.” By providing space on their grounds for the vigil, the museum more than lived up to their mission statement, and their example should be followed by other museums and arts institutions.

Also addressing the vigil was the Reverend Mark Nakagawa, who talked about his work with the Nikkei Interfaith Council, a grouping of Christian Churches and Buddhist Temples in the Little Tokyo area. He spoke of how the council was engaged in outreach programs with the Islamic community of Los Angeles in these times of crisis, and urged one and all to defend the democratic rights of Muslim Americans.

Rev. Nakagawa outlined his work with the Christian-Muslim Consultative Group of Southern California, which was founded in 2006 for the express purpose of bringing Christians and Muslims together “to enhance mutual understanding, respect, appreciation, and support of the Sacred in each other.”

The Rev. Nakagawa’s impassioned call for religious freedom was followed by a short address from Noriaki Ito of the Higashi Honganji Buddhist Temple. An outstanding member of the Japanese American community in Los Angeles, Ito currently sits on the Board of Directors of the Japanese American Cultural and Community Center, and served as the Past Chair of the Little Tokyo Community Council. He is actively involved in the preservation of L.A.’s Little Tokyo district. Mr. Ito came to the vigil wearing a formal black and white “wagesa” (Buddhist robe), and he spoke with the wisdom of a Buddhist Kyoshi (teaching priest), calling for unity between all people of faith, and the defeat of religious intolerance.

Ms. Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga gave the most powerful of testimonies during the vigil. A California-born U.S. citizen, Aiko and her family were swept up in the relocation of “enemy aliens” after President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 in 1942. As a 17-year-old she and her family were sent to the Manzanar War Relocation Center, a barracks-like camp in California where she gave birth to her daughter under crude living conditions. Aiko and family were transferred to the bleak Jerome internment camp in Arkansas, where they remained imprisoned until 1944.

As Aiko described her life in the Manzanar and Jerome internment camps, from the same spot where thousands of Japanese Americans had been shipped off to those unwelcoming camps all those years ago, tears came to my eyes.

The same demons of racism, ignorance, and fear that sent Aiko to those wretched camps are once again plaguing U.S. society (did they ever go away), only this time they are pursuing Muslim Americans. The 86-year-old Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga, speaking passionately and with great authority, exhorted vigillers from a megaphone to defend the civil liberties of Muslim Americans as they would defend their own.

California State Assemblymember Warren Furutani, also addressed the vigil, and in his eloquent way urged people to stand united with their “Muslim brothers and sisters” in opposing all forms of racism, discrimination, and religious intolerance. Mr. Furutani waxed poetic as he railed against certain sectors of U.S. society, “where hate can be purchased wholesale,” an obvious reference to the right-wing “talk” radio hosts who daily spew out vile and unbearable lies about Islam and Muslim Americans.

Jan Tokumaru of Nikkei for Civil Rights & Redress, read a statement at the vigil that had been published by the NCRR for the occasion. It read in part;

“Nine years ago – just days after Sept. 11 – Nikkei for Civil Rights and Redress (NCRR), along with other organizations including the Japanese American Citizens League, the Japanese American Cultural and Community Center, the Japanese American National Museum and the Little Tokyo Service Center, sponsored a candlelight vigil in Little Tokyo to remember the victims of 9/11 and to speak in defense of Arab Americans, Muslim Americans, and South Asians who were being maligned as ‘terrorists,’ physically attacked, and even murdered in places such as Arizona. Since 9/11, attempts to marginalize and target Muslim Americans as a ‘suspect’ community sympathetic to terrorist incidents throughout the world continue.

(….) Japanese Americans remember all too well how it feels to be a community singled out with suspicion, marginalized and viciously attacked by the media. Despite many efforts to show their loyalty to this country, Japanese were not trusted as reflected in General DeWitt‘s statements: ‘A Jap is a Jap,’ and ‘I have no confidence in their loyalty whatsoever.’ The constant barrage of lies in the media became accepted as truth by the American public.

(….) Although the situation is not as dire for Muslim Americans now as it was for Japanese Americans during World War II, NCRR is concerned that the climate of intolerance and fear being created could, under certain circumstances, lead to the stripping of civil liberties and religious freedom for Muslim Americans. Even worse is the violence resulting from such ignorance, such as the stabbing in New York last month of a 44-year-old taxi driver after his passenger asked if he was a Muslim.

(….) NCRR encourages Japanese Americans and all Americans to speak out against anti-Muslim lies and attacks. At a speech given several years ago, Dr. Maher Hathout, a Muslim American leader, said ‘as long as there is one candle lit, there is no darkness.’ Speaking symbolically, he was referring to the struggle of the Palestinian people against occupation – that as long as there was even one person willing to struggle against injustice, there could not be total darkness or oppression. In a similar spirit, NCRR hopes that many candles can be lit on Sept. 9, to show the American people’s commitment to the truth – not lies and distortions – and for justice, peace, religious freedom, and equality – precious values that we hold dear.”

At the end of the vigil, organizers asked participants to form a giant peace sign by grouping themselves together around an outline drawn on the museum’s plaza. A handful of photographers, myself included, were given access to the museum’s rooftop to take photos of the event. The aim was to present a gift – an image of solidarity and peace – to the beleaguered Muslim citizens of the United States.

As of this writing, save for one solitary article published by the Rafu Shimpo Japanese daily newspaper of Los Angeles, not a single news media source in the U.S. (aside from this web log), has reported on the silent vigil that took place at the Japanese American National Museum.

[A full listing of the speakers at the vigil includes – Reverend Mark Nakagawa of the Centenary Methodist Church; Noriaki Ito, Rinban (head minister) of the Higashi Honganji Buddhist Temple; Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga, a WWII internee; Dana Fujiko Heatherton, 2009 Nisei Week Queen and a J-Town Voice activist concerned with the preservation of L.A.’s Little Tokyo, California State Assemblymember Warren Furutani, Jan Tokumaru of the Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance, Aziza Hasan from the Muslim Public Affairs Council, and Ilham Elkoustaf from the Council on American Islamic Relations.]