Eco-Vandals Pour Oil on Gustav Klimt Painting

I have always been captivated by the art of Gustav Klimt, so I was enraged to hear that so-called “climate activists” had attacked one of his renowned paintings. On Nov. 15, 2022, two members of the eco-extremist group Letzte Generation Österreich (Last Generation Austria), raided the Leopold Museum in Vienna, Austria. One carried a 2-Quart rubber hot water bottle filled with viscous black oil; he kept it hidden beneath his shirt.

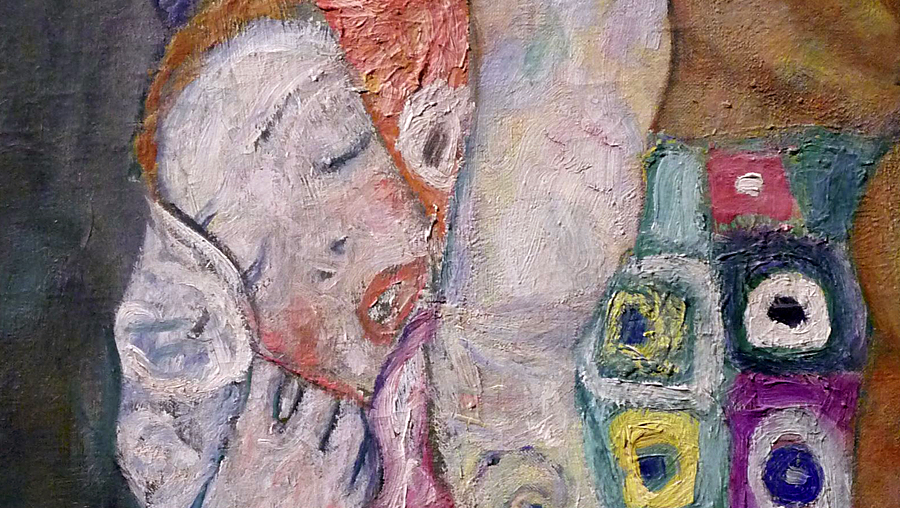

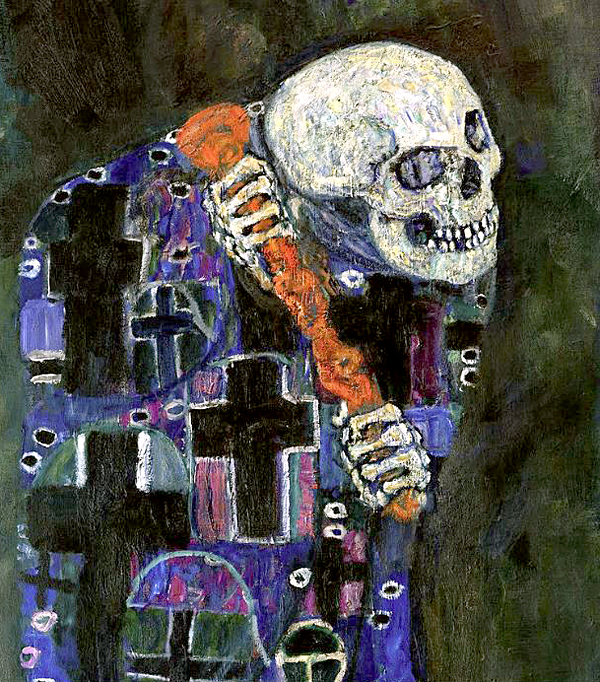

They entered the museum and quickly made their way to Tod und Leben (Death and Life), a painting created by Gustav Klimt in the early 1900s. The hoodlum with the hot water bottle pulled it out from under his shirt, unplugged it, and hurled the black oil onto the artwork (it was protected by a glass shield). As the oil dripped to the floor, the vandals prepared to glue their hands to the oily picture frame—a museum guard intervened; he wrestled with the offender who chucked the petroleum, and successfully removed him from the gallery.

That left the vandal who managed to glue himself to the painting’s frame—he was left bleating “Stop destroying humanity with fossil fuels. We are rushing towards a climate hell.” Another guard entered the room and tried to stop someone from video-recording the spectacle. Since the Last Generation gang uploaded a video of their assault on Klimt’s painting to their Twitter account, it can be assumed the videographer was also a member of Last Generation.

The Austrian police finally arrived and the eco-extremists were removed from the museum but not arrested. A police spokesman said the arrestees were considered subjects of “a complaint for material damage and disturbance of public order.” That should teach ‘em a lesson, eh?

On the day of the vandalism the museum was free due to the largesse of OMV, the Austrian multinational petrochemical company headquartered in Vienna. No doubt this triggered Last Generation Austria, who thought it appropriate to splatter their targeted painting with oil.

In the aftermath of their attack, Last Generation Austria released a Twitter statement regarding their criminal actions: “URGENT: Klimt’s ‘Death and Life’ in the Leopold Museum covered in oil. People of the last generation poured oil on the Klimt painting ‘Death and Life’ in the Leopold Museum today. New oil and gas wells are a death sentence for humanity.”

While Last Generation Austria boasted of having “poured oil on the Klimt painting,” corporate media hacks reported the “climate activists” were alleged to have poured: “liquid,” “dye,” “black paint,” “black liquid,” or a “black substance” on the artwork. It’s embarrassing that the media calls the culprits who sullied Klimt’s painting “climate activists,” but then, the once respected profession of “journalist” has became an embarrassment.

These “climate activists” are not engaged in non-violent activism, instead they pursue outright vandalism. Truth demands that they are accurately identified for what they are… eco-vandals. It should come as no surprise that the anti-art vandalism of these miserabilists has in fact decreased sympathy for their crusade. I fear they are evolving into the eco-terrorists of the future.

An odd thing about the eco-extremist war on art, is how the vandals make unschooled statements that attempt to link their acts with the art they deface.

When Just Stop Oil vandals glued themselves to a copy of Leonardo Da Vinci’s The Last Supper in London’s Royal Academy of Arts, they said climate collapse would bring famine and the last supper for the world. When Italy’s Ultima Generazione (Last Generation) glued themselves to the frame of Botticelli’s Spring in the Uffizi Gallery, they said climate collapse would keep us from seeing spring days. With Klimt’s Death and Life, their statement was oil is a death sentence for humanity.

The International Council of Museums (ICOM) located in Germany, reacted to the eco-extremist war on art by drafting a statement condemning the vandalizing of art museums for political causes. Directors of 92 major international art museums have signed the statement, among the signatories are The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), Gallerie degli Uffizi (Florence), and the Detroit Institute of Arts. The statement in part reads:

“In recent weeks, there have been several attacks on works of art in international museum collections. The activists responsible for them severely underestimate the fragility of these irreplaceable objects, which must be preserved as part of our world cultural heritage. As museum directors entrusted with the care of these works, we have been deeply shaken by their risky endangerment.

Museums are places where people from a wide variety of backgrounds can engage in dialogue and which therefore enable social discourse. In this sense, the core tasks of the museum as an institution – collecting, researching, sharing and preserving – are now more relevant than ever. We will continue to advocate for direct access to our cultural heritage. And we will maintain the museum as a free space for social communication.”

Gustav Klimt painted Tod und Leben (Death and Life) between 1910 and 1911, and later repainted and revised the work between the years 1915-1916. Klimt showed the work publicly for the first time at the International Art Exhibition in Rome of 1911, winning a gold medal for his creation.

Gustav Klimt was a founding member of the 1897 Vienna Session movement. Along and his fellow Secessionists they challenged the academic art of the day. In 1898 the group began publishing its own journal, Ver Sacrum (Latin for “Sacred Spring”). The journal advanced Secessionist ideas, and in its first issue the Austrian writer and playwright Hermann Bahr delineated their principles:

“Our art is not a fight of modern artists against old ones, but the promotion of arts against the peddlers who pass for artists and have a commercial interest that prevents art from flourishing. Commerce or art, that is the issue before our Secession. It is not an aesthetic debate, but a confrontation between two states of the spirit.”

Written in January 1898, Bahr’s pearls of wisdom reach into the present, they have become a maxim for thoughtful contemporary artists. I’ve seen a number of Klimt’s paintings over the years, and was always impressed by his “impasto” technique; paint applied by brushes heavy with paint and applied in thick brush strokes. It’s not easy to see this in reproductions, where his works appear smooth and polished. However, up-close his paintings are full of rough and aggressive textures, but always controlled by a masterful hand.

In 2012 my wife and I visited the Getty Center in Los Angeles to see the exhibit Gustav Klimt, The Magic of Line; it was a memorable and popular exhibit. However, there was one historic oversight in the show I couldn’t get out of my head; it had to do with the Getty’s captioning of Klimt’s preliminary sketches for his Faculty Paintings.

In 1894 the Austrian Ministry of Education gave Klimt a commission to design ceiling paintings for the University of Vienna (founded in 1365). Klimt was asked to create paintings symbolizing Medicine, Jurisprudence, and Philosophy. The works became knows as the his Faculty Paintings. The University was outraged by the finished paintings, viewing them as pornographic. Klimt returned the commission money and sold off the three 13-foot-tall paintings. Eventually Philosophy and Jurisprudence would end up in the collection of Klimt’s patron August Lederer, and Medicine became part of the Austrian Gallery collection.

My wife noticed a discrepancy in the wall text caption for the displayed Faculty Paintings sketches; it said the paintings had been “destroyed” in 1945 but the exhibit book said the paintings were “burned in a fire.” No other details were mentioned… but what else happened in 1945?

The question of who destroyed the Faculty Paintings by fire, and why they did so, drove me to write a 2012 essay titled: Gustav Klimt: At The Getty.

My article details Austria’s 1938 invasion by the Nazis, and how they seized art treasures owned by Jews; the art collections of August Lederer and the Austrian Gallery were stolen by the Nazis. Many works by Klimt were included, not because he was Jewish (he was not), but because he cooperated with, and had an affinity for the Jewish people. Moreover, the Nazis condemned modern painting and sculpture as degenerate art, because, they said, it was influenced by Bolsheviks and Jews.

The Nazis hid a large part of their stolen art treasures in Immendorf Castle, located in Lower Austria. When Hitler committed suicide and the Soviet Red Army captured Berlin in 1945, the Nazi regime disintegrated. To prevent their stolen art from falling into the hands of their enemies, the Nazi SS set charges and blew up Immendorf Castle, the resulting fire obliterated the seized collections of August Lederer, the Austrian Gallery, the Museum for Applied Arts of Vienna, and many of Klimt’s works—including the three Faculty Paintings.

It’s a certainty the incurious eco-vandals of Letzte Generation Österreich are pig-ignorant when it comes to the Nazi confiscation and destruction of Gustav Klimt’s wondrous paintings and drawings. The ignoramuses of Last Generation without a doubt think themselves cleaver, virtuous, and morally justified in pouring oil on a Klimt masterpiece.

Regardless, people around the world when seeing that big, oily black splotch covering Klimt’s painting, will think of how the Nazis desecrated art and persecuted artists. I can’t see how Last Generation can avoid that comparison.

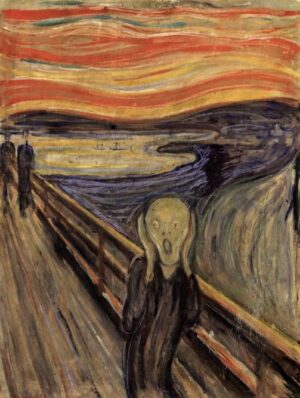

UPDATE: On Nov. 11, 2022, three eco-vandals from the Norwegian group “Stopp oljeletinga” (Stop Oil Exploration), attacked Edvard Munch’s 1893 masterpiece The Scream housed at the National Museum of Norway.

Two vandals attempted to glue themselves to the painting while shouting “I scream for people dying” and “I scream when lawmakers ignore science,” while a third video-taped the assault. The three vandals were women from Finland, Denmark, and Germany.

Museum security guards prevented the vandals from gluing themselves to the painting’s frame; all three were arrested.

A spokes-goon for the group told the Associated Press, “We are campaigning against ‘Scream’ because it is perhaps Norway’s most famous painting.” Yeah, right… and this artist filing his report in Lost Angeles, says… “I scream against barbarians who vandalized art!“