WITHERED Arts Journalism in LA?

On March 24, 2005, a public forum titled Whither Arts Journalism in LA? was held on Olvera street in downtown Los Angeles on the topic of arts journalism in LA. Moderated by Adolfo Guzman Lopez, the panelists included art critics Christopher Knight (LA Times), Peter Frank (LA Weekly), Malik Gaines (artUS magazine), and Caryn Colemen (art.blogging.la). The event attracted an audience of nearly 100. In addition to the professional artists and journalists, there were a good number of students, teachers, gallery owners and the just plain curious in attendance. I was present at the forum and have a number of observations to make on the proceedings.

Ms. Coleman posted a summation of the event on her web log, where she stated: “The panel on Arts Journalism in Los Angeles went really well tonight with only a slight bit of intensity at the end.” That intensity at the end was actually the most revelatory and interesting part of the entire forum.

The first half of the panel discussion was an examination of current art journalism and where it might be headed, with all panelists generally agreeing that independent art reporting was vital and much needed. Every one concurred that art magazines were beholden to their advertisers, and so no truly impartial voice could be found there. Mr. Knight explained his position plainly enough, “There’s not a problem with art writing, but with art publishing.” The understated suggestion that culture and art production is controlled or shaped by money warranted further discussion but that wasn’t to be, at least not at this particular forum.

Things became more interesting when the moderator opened the second half of the event to questions from the audience, and it was here that panelists revealed their bias and the divisions in the crowd were laid bare. This first became evident when a man addressed himself to the full panel and asked “What makes good art?” It was an honest question that deserved an intelligent response, but instead the panelists laughed out loud and rolled their eyes, as did a few people in the crowd.

An evasive response came from Mr. Frank, “It’s like porn… I know it when I see it.” While a humorous retort, Frank’s equating art with pornography did nothing to clarify what criteria the panel of art critics uses when judging art. The panel simply refused to consider the question and its implications, with Mr. Knight flatly saying that it’s “hard to say what is good or bad.” It seems that in every other sphere of human activity, it’s not difficult to ascertain the difference between superior and substandard work.

We recognize awful writing, bemoan poorly crafted music, abhor bad science, and make absolutely no excuses for second-rate mechanics, cooks, and doctors. But when it comes to art all things are good and equal. The postmodern ethos of relativism in art prevents condemnation of even the most shoddy and mediocre art works.

When panel members were asked “What artists or art movements do you want to champion?”, Mr. Gaines said “I’ll probably never champion a movement, but I’m interested in the return of craft.” With that I was offered a shred of hope, until I realized Gaines was not talking about skill, talent, or expertise but of “craft” in the sense of what kindergarten children do when given rudimentary craft materials. Gaines was talking about “conceptual problem solving” using bits of clay, cloth, and found materials.

At this point Mr. Knight said, “I think we’re in a post-movement world and the critique of institutions is over.” Knight’s statement reminded me of the ridiculous early 1990s axiom that the “The End of History” had occurred with the demise of the Soviet Union. Former US State Department planner Francis Fukuyama wrote an article in 1989 titled The End of History, his contention being that history is directional and its endpoint is “capitalist democracy.” Fukuyama argued that “history,” the grand pageant of human political evolution, had come to an end since the big questions had been answered with the fall of the Soviet state. Capitalism had triumphed, constituting the “end point of mankind’s ideological evolution.”

I’m not certain what type of art world utopia Knight thinks we have reached, where questions of artistic movements and their critiques have become irrelevant, but I profoundly disagree with his line of reasoning. All historic epochs have cynics who pontificate that everything under the sun has been accomplished, and that there are “no more movements” on the horizon. Such proclamations are the clearest sign that all hell is about to break loose.

Artists have always reacted to the world around them. To declare that we are in a “post-movement” period while the world is burning is nothing short of delusional. To proclaim that “the critique of institutions is over” at a time when nearly all institutions are corrupted and crumbling, is to dance with the devil. It is the greatest irony that on Olvera street, just outside the venue that hosted the forum, stands América Tropical, the now whitewashed revolutionary mural by David Alfaro Siqueiros.

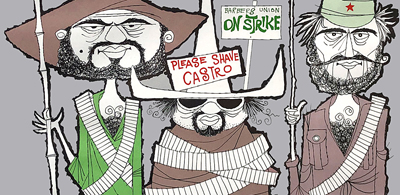

The panelists became annoyed when a young man in the audience stood to say that “Artists and art critics speak in a specialized language that is not understood by the general public.” He spoke clearly about how contemporary art has alienated people, and that it’s a societal crisis when “most Americans don’t go to galleries and museums.” Rather than take some responsibility for this admittedly dreadful situation, the panelists preferred instead to morph into the three monkeys—Hear no evil, see no evil, speak no evil.

Colemen declared “I don’t think the general public is interested in art,” Frank quipped “or ever has been,” and Knight cracked “… or ever will be.” The young man snapped back with, “That’s a cop-out, it’s your duty to educate people concerning art,” to which the panelists showed unanimous displeasure. Mr. Knight expressed the panel’s obvious consensus, “Art isn’t for everyone, it’s for anyone, and there’s a difference.”

Again, I take exception to the opinions of Knight and his cohorts on the panel. I believe that art is for everyone, and its appreciation is more a matter of acculturation and education than of anything else.

Cultural literacy is low in the US, not because Americans are uncultured dim-wits, but because there is little in our society that supports the arts. If the corporate press gave as much emphasis to art as they do to sports, you can rest assure that the US would be a very different place. One is not born with the innate skills of reading and writing, these are things that must be taught, so too with the skill of appreciating and understanding art. I believe that the artist, and yes, the art critic as well, must in part help educate people when it comes to aesthetic matters. Who else is there to do this?

It is a thoroughly elitist world view that sees people as too stupid to enjoy the arts. People have not abandoned art because they are stupid… they have abandoned it because art has become stupid.