The Biennale: “Dearth in Venice”

The 51st Venice Biennale opened on June 12th, 2005, and artists, patrons, curators, collectors and the general public will view the latest in contemporary art until the festival closes in November. It’s been said that this biennale has abandoned the display of gimmicky artworks designed to shock in favor of more subdued statements, and that this year’s festival is a triumph for women – but I see little evidence of these allegations.

It has been asserted that this biennale is less political than previous ones, even as Bush’s State Department appointed Ed Ruscha as America’s “official representative.” While it’s true that not a single artist bothered to make even a token statement on the inferno that is the Iraq war… real world politics were made manifest in other ways.

Having visited Venice I can attest to the beauty of this metropolis built upon the sea. The richness of the city’s Byzantine and Renaissance architectural styles is overwhelming, and its hundreds of palaces, churches and public buildings present the works of the matchless Venetian school of painters. The artists of Venice helped to establish oil paint as a medium in artistic production, and as I strolled through the city’s ancient galleries gazing upon master works by Giovanni Bellini, Jacapo Tintoretto and Titian I was left with the impression that the city well represents the highest achievements of Western art.

Which is part of my displeasure at seeing the former bastion of the renaissance transformed into a roosting place for flocks of wealthy art patrons, dealers, and other buzzards looking for the latest postmodern “masterpiece” to add to their collections.

My feelings regarding the biennale are shared by Guardian art critic, Jonathan Jones, who eloquently tells the tale of woe in his piece entitled, Dearth in Venice. The Venice Biennale has more resemblance to a gated community for art snobs than a true public celebration of art.

The kingpin of that gated community would have to be Paul Allen, the co-founder of Microsoft. Allen moored his yacht off of Venice’s famous Grand Canal along with the numerous yachts belonging to his fellow fat cats. But at 413-feet-long and equipped with a screening room, swimming pool, an art gallery housing his private collection, and a helicopter, Allen’s colossal yacht dwarfed not only the tiny picturesque gondolas – but the yachts of the other captains of industry as well.

Allen’s private cruiser is aptly named The Octopus, and its tentacles reach around the world. While Mr. Allen whooped it up with his billionaire buddies at the biennale, Microsoft launched a new China-based Internet portal in Beiijing.

A collaborative project with the communist regime, MSN’s system bars people from using the following words in its search engine, “democracy,” “freedom,” “human rights,” “demonstration,” and “Taiwan Independence.” The money made from this contemptible deal will no doubt help Mr. Allen snatch up some hot new art at the biennale – or at least make it possible for him to obtain another yacht. The ostentatious flaunting of wealth seems to be the spirit of the Venice Biennale, and one of the first things visitors see when entering the grounds are banners from American artist Barbara Kruger, which read “Money,” “Power,” and “You make history when you do business.”

The sad thing about Kruger’s postmodernist diktats in the context of this particular setting, is that they have absolutely no sense of irony, sarcasm or even humor. They have no power in the land of the money bags. They are more confirmation than critique.

As I’ve already noted, the 51st Venice Biennale is being touted as a breakthrough for women, and those who make this assertion point to the Spanish curators Maria de Corral and Rosa Martinez, who are the first women to have ever organized the event in its 110-year history. That they filled the curatorial positions of this most vaunted festival is notable – but a breakthrough?

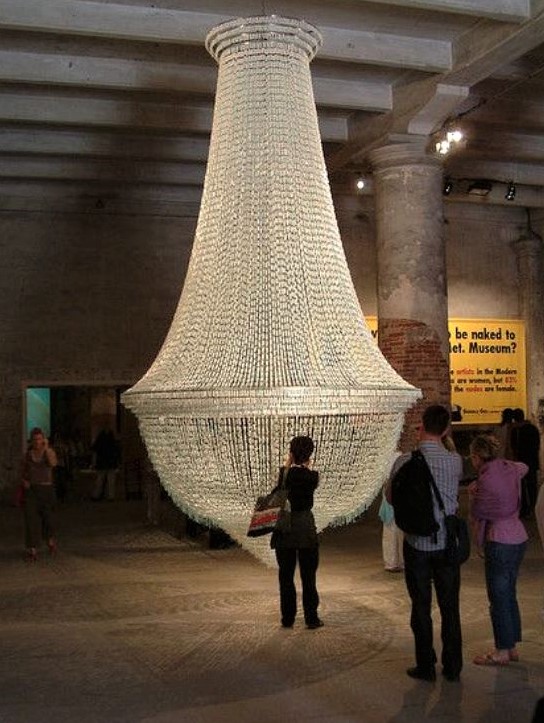

They recommended that the aforementioned Barbara Kruger receive a Golden Lion Lifetime Achievement award for her contentious photomontage works, but what else is there to show for their appointment? We are offered an installation by American artist Jennifer Allora that features a life-sized realistic hippopotamus made of mud, upon which a real woman sits and reads while occasionally whistling. There’s the conceptual art of Portugese artist, Joana Vasconcelos, who created a chandelier made of tampons entitled The Bride.

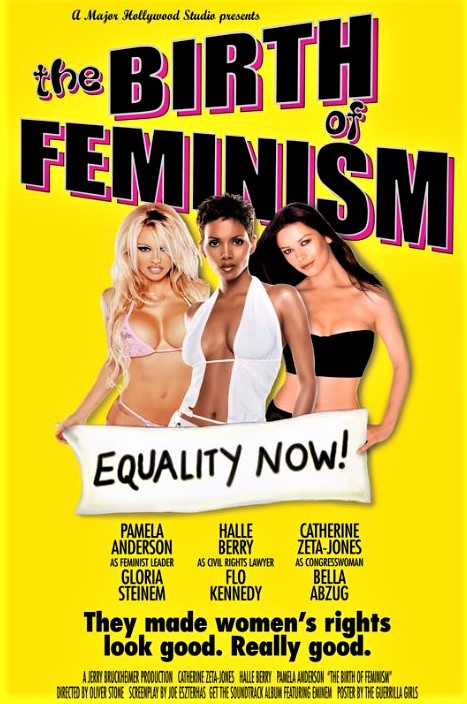

And last but not least, the Guerilla Girls exhibited their so-called pop art posters, one of which is pure text and reads “Less than three percent of artists in the modern art sections are women, but 83 percent of the nudes are female.” That’s fine as an agitational slogan but it’s lousy art. The Birth of Feminism poster from the Guerilla Girls looks like any other advertisement for the latest inane Hollywood jiggle fest, except we are to believe that this particular poster carries with it a subversive feminist subtext.

The Guerilla Girls are most likely elated over having succeeded at turning a monotonous advertising agency style poster into “high art,” but how a Photoshop manipulated image of scantily clad bikini bimbos advances feminism or qualifies as fine art escapes me. I’ll take Mary Cassatt or Frida Kahlo over the Guerilla Girls any time. Aside from these few examples, the curators exercised caution in pushing a feminine perspective – so much for the great advances of women artists.

Suffice it to say, the Venice Biennale places great attention on conceptual and installation works, with traditional painting given only marginal consideration. Commenting on the event, Glenn D. Lowry, director of the Museum of Modern Art, was quoted in the New York Times as saying “The art world is in a transitional moment, with so many new people coming in to it, it all hasn’t settled yet.”

Which I suppose is the polite way of saying the art world is out of control, makes no sense, and is in a complete state of disarray and chaos. I’ve always maintained that great art springs from chaotic times, but you’ll have to look beyond the pavilions of the Venice Biennale to find it.