Degenerate Art: Then and Now

The Tate Modern in London currently has on display an exhibit called Degenerate Art, a small showing of German Expressionist paintings that runs until October 30th, 2005.

The name of the Tate show comes from the infamous Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibit mounted by the Nazis in 1937.

Heralding the Nazi regime’s policy towards the arts, that exhibit was the most detestable campaign to have ever been launched against modern art.

Jonathan Jones, writing for the U.K. Guardian, had this to say about the Tate show: “It would be great to see a full-scale exhibition. In fact, it would be worth reconstructing the entire Degenerate Art exhibition. The restaging would, I suspect, profoundly alter our view of modern art.”

In 1991, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) came close to a full restaging of Entartete Kunst, and being an ardent fan of German Expressionism, I was the first in line to view LACMA’s Degenerate Art: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany. I was not disappointed by the comprehensive overview offered by the museum, which included a full scale model of the original Nazi exhibition, along with ephemera from the exhibit like tickets, catalogs, advertisements and other bits of memorabilia.

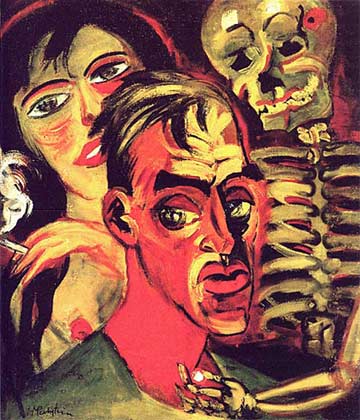

The LACMA show also included rooms devoted to the Nazi view of literature, music and film—but the focus of the exhibit was of course the paintings and sculptures created by those artists the fascists considered “enemies of the German people.” On display were artworks by Max Beckmann, Emil Nolde, Otto Dix, George Grosz, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and many other notables who so influenced my own course as an artist.

Since the LACMA exhibit is history, and the Tate show is inaccessible to all save those living in London—you might want to visit my Art For A Change web site, where I host a history of German Expressionist art that includes the works of Max Pechstein, Otto Dix, August Macke, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Conrad Felixmuller, Max Beckmann and many others.

By 1937 the Nazis had removed more than 20,000 modernist artworks from museums and galleries, bringing them together for Entartete Kunst, a touring exhibit whose sole objective was the scorn and derision of modern art. Artworks were crowded into the Archäologisches Institut in Munich and given hand-scrawled mocking captions. Poorly hung and intentionally displayed with inadequate lighting, the artworks were surrounded by slogans like, Incompetents and Charlatans, An insult to the German heroes of the Great War and Nature as seen by sick minds.

The exhibit became one the most successful displays of modern art in history, the first blockbuster art show, with around 3 million people viewing it before its thirteen-city German and Austrian tour was completed in 1941.

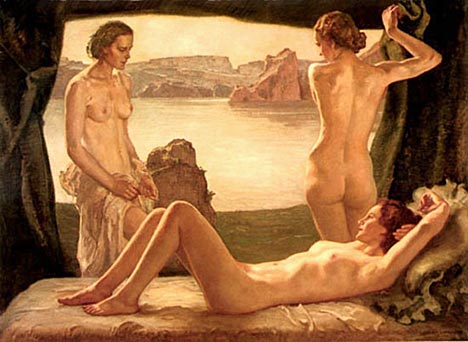

The Degenerate Art show was actually held in contrast to the Grosse Deutsche Kunstausstellung (Great German Art Exhibit), where Nazi-approved realist paintings and sculptures were displayed.

Held annually in Munich from 1937 until 1944, historic, idyllic and mythological German subjects were treated in romantic, academic and classical realist styles. Artists like Ernst Liebermann (1869-1960), Sepp Hilz (1906-1967), and Ivo Saliger (1894-1987), presented scenes that extolled traditional family values, motherhood, health and work, athleticism, rustic peasant life, faith in leadership and glorification of the military.

Such works could be deceptively benign, as is the case with Libermann’s By the Water (shown above). Many looking at this painting today would merely see an “apolitical” study of three nudes—yet, it’s an outstanding example of the Nazi celebration of beauty, sexuality and physical culture through classical aesthetics.

Nudity in art was never censored by the Nazis, providing it helped to communicate fascist ideology. In part that entailed the idealization and objectification of femininity, while extolling masculine strength and physical superiority.

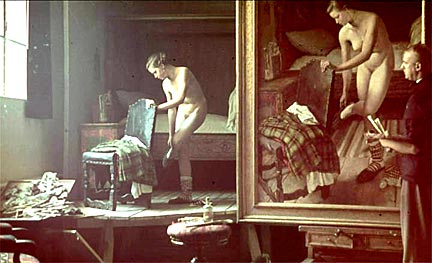

Sepp Hilz was an academically trained realist painter who came to be known as Bauernmaler (the painter of peasants).

His classical style oil paintings of Bavarian farmers, beautiful village girls, and the rustic lives of simple country folk, were observations of rural life seemingly free of political statement.

Hilz was a technically dazzling painter who never created an overtly political artwork, he was a portraitist who concerned himself only with matters of aesthetics when it came to making art. Which begs an interesting question relevant to our own time. If an artist produces nothing but “apolitical” works, is the artist then above politics?

Ironically, as a successful proponent of “realism” in painting, realism did not permeate Hilz’s idealized view of the world.

His charming and inoffensive paintings concealed the malignant cancer destroying his country. No doubt Hilz opposed modernist artists for depicting the screaming insanities that had become everyday life in Germany. It’s a certainty he loathed the tortured, garish and distorted artworks of the Expressionists, and he most likely applauded their censorship and banning as a “renewal” for art.

From 1938 to 1944, Hilz presented no less than twenty-two paintings at the Great German Art Exhibit, with none other than Adolf Hitler purchasing two of them.

Nazi Reich Minister of Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, purchased Bäuerliche Venus (“A Country Venus,” shown above and at right), which became a wildly popular iconic painting for the German right-wing.

Hilz was so favored by the Nazis that Hitler financed the construction of a special studio for the artist in 1939, and in 1943 the painter received the title of “Professor” from Reich Minister Goebbels.

Another favored artist included in the Great German Art Exhibit was Ivo Saliger, whose Judgment of Paris (1939), depicted the Greek myth… but with a twist. Contemporary viewers see Saliger’s canvas as nothing more than an academic painting, an exercise in classical figurative realism, yet the work is an ideological diatribe.

Saliger portrayed Paris dressed in a Hitler Youth uniform as he decided upon the most beautiful example of Aryan womanhood. Again, a difficult question arises, that of identifying the ideology inherent in images placed before us. If I had not revealed to you the story behind Saliger’s painting, would you have identified the artwork as implicitly fascist?

Today arguments continue to rage over what defines a work of art. Witness the Art Renewal Center (ARC), which regards the academic school of late 19th Century European painting as not only the pinnacle of all artistic achievement, but the only way forward for artists today.

The ARC champions the academic painter, William Bouguereau, who was the president of the painting section of the Paris Salon in 1881 and an unwavering enemy of the Impressionists. It’s no wonder then that I read in the ARC website letters section, a correspondence praising Ivo Saliger for being a painter “of classical subjects.” I wouldn’t be surprised if tomorrow the ARC issued a salvo against Degenerate Art.

I’ve spent much time on this web log criticizing the follies and excesses of postmodern artists, but my critiques should never be confused with the voices who clamor for the past. When letting my poison arrows fly against the talentless swindlers in today’s world of art, I’m always wary of being aligned with those who seek to dismiss, control or suppress artistic expression.

Every aesthetic vanguard has historically been confronted by the narrow-minded who exclaim, “that isn’t art” or “I could do that.” I’m well aware of the forces that have mounted major attacks against the arts—assaults that have resulted in censorship and the closing of exhibitions. I’m also well-versed in the sad chronicle of regimes who’ve suppressed all forms of independent vision in favor of an insipid and stilted realism.

Gesundes Volksempfinden, or “healthy folk sentiment,” became the official criteria for judging artworks under the Nazi regime, and when Hitler said that “anybody who paints and sees a sky green and pastures blue ought to be sterilized,” he meant it.

While the world has changed since the Nazis held their Entartete Kunst exhibition, polarizing social dynamics have not. Today a deadly new strain of censorship shadows creativity and many artists are infected with a self-imposed variant. The solution is to meet adversity with the same steadfastness displayed by the German Expressionists, whose works after all outlived those of their adversaries.