L.A.’s Siqueiros Mural To Live Again

On August 2nd, 2006, after spending my entire adult life reading about América Tropical, the internationally famous mural painted in Los Angeles by Mexican Muralist master, David Alfaro Siqueiros, there I was, for the very first time – barely inches from the huge masterwork. Just the day before I had received a telephone call from friend and associate, Luis Garza, who sits on the city’s Siqueiros Mural, Events, and Marketing Committee overseeing the restoration of the mural. Garza had called to invite me to the important press conference where L.A. Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa would have exciting news regarding the mural.

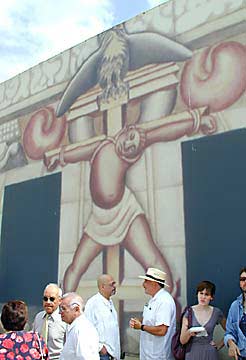

Mayor Villaraigosa’s press conference took place early in the morning on Olvera Street, the city’s founding avenue and location of the Siqueiros mural. That morning the historic area of the city, known officially as the El Pueblo Historic Monument, was bristling with television, newspaper and radio reporters eager to cover the story. Before a large crowd of city officials, local business people, artists and reporters, the Mayor publicly announced the city’s collaboration with the Getty Foundation on finalizing conservation efforts and providing public access to the mural. At last, the day many of us had dreamed of for years had finally arrived. It was official, a budget for the project had been approved – the renowned mural would live again.

At the press conference Mayor Villaraigosa remarked: “The people of the city of Los Angeles will finally be able to view this cultural treasure long obscured from sight. The mural, while controversial in its time, will allow adults and children of all ages to learn about and appreciate the diverse history of this city, the importance of freedom of artistic expression and the origins of the muralist movement in this city.” The Mayor added, “While people can agree or disagree with the message, what’s important is that it was art, and art, while sometimes controversial, is important – because what it does is to lift the soul.” The Mayor’s comment that the mural was “controversial in its time” treats the work as if it were safely and firmly rooted in the past and without relevance to our present political situation. In fact, the work may be more provocative today than when it was first painted – especially during this time of world crisis. Rather than shying away from the artist’s political message to concentrate on his mural as purely an artistic triumph, we should celebrate and defend the anti-Imperialist politics of América Tropical. That being said, I must applaud the Mayor’s bold leadership in campaigning for the conservation of this priceless and influential artwork.

After his comments the Mayor introduced the three representatives from the Getty who were on hand to talk about the museum’s role in the conservation project. Deborah Marrow, Interim President and CEO of the J. Paul Getty Trust, Timothy Whalen, Director of the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI), and Joan Weinstein, Interim Director of the Getty Foundation. The three spoke of the Getty Foundation’s commitment to the project, from the construction of a protective shelter and viewing platform for the mural, to the installation of an interpretive center that would place the artwork in historical and artistic context. The overall cost of the project is $7.8 million, with the Getty and the City of Los Angeles basically splitting the expense. The Mayor next introduced Judy Baca, famed L.A. muralist and the Founder/Artistic Director of the Social and Public Art Resource Center of Venice, California. She gave an impassioned speech on the importance of the Siqueiros mural and of muralism in general, noting L.A.’s reputation as the mural capital of the world, and imploring those present to support a revitalization and expansion of the L.A. muralist movement.

As the press conference concluded, officials announced that everyone was invited to the Italian Hall, the historic building on Olvera Street where Siqueiros painted his 80-by-18 foot rooftop mural on an outside second-story wall. We were given a rare opportunity to stand on the roof where we could examine the mural. In actuality, the artwork is now sheltered by a metal covering, over which is stretched a digital reproduction of the mural as it looked before it was censored by a coat of whitewash in 1932. The Getty’s plan is to preserve the mural just as it is – a ghost image – and not to repaint or fully restore it. There are several reasons for this approach, the chief cause being that the artist painted his work in a way that had not yet been proven. Abandoning the traditional method of fresco painting whereupon tempera pigments are painted onto fresh limestone plaster, the experimentally minded Siqueiros painted his mural on concrete using Pyroxylin, a newly developed material that was primarily used to paint automobiles. Conservators have found that the paint’s adhesion to the wall was flawed, adding to the problems of restoration.

From atop Italian Hall there is a dazzling view of downtown L.A., and one can just imagine the splendor of the site once the Getty builds the mural’s protective shelter and viewing platform. A representative of the Mayor’s office requested that all of the artists present stand before the mural so as to be photographed – a tribute to Siqueiros and the impact the Mexican Muralist had upon the artistic community of Los Angeles. I noticed that one of the photographers taking pictures of the proceedings was an old acquaintance – L.A.’s own Gary Leonard. He deftly took a quick shot of me, and naturally we ended up talking about the significance of the day. Interestingly enough, Leonard is related by marriage to Philip Stein (aka Estaño), the American social realist artist who for ten years worked in Mexico with Siqueiros on creating some of the master’s finest works.

Fleeing repression and persecution in Mexico, Siqueiros came to Los Angeles in 1932. During his six month stay here he painted three important murals before being brusquely deported by the U.S. government. His first mural was Mitin Obrero (Worker’s Meeting), a two story creation painted on the side of a building at Chouinard School of Art – where he had been teaching mural painting techniques. It was the very first time anyone in the world had used an industrial spray gun to paint a mural directly on cement. Finished in July 1932, the mural was almost immediately painted over by right-wing authorities. Siqueiros’ second mural was América Tropical, and his third, Retrato del Mexico de Hoy (Portrait of Mexico Today), only survived because it had been painted on the wall of an outdoor patio at the private residence of film director, Dudley Murphy.

Back in 2002, I wrote about the experience of attending the Santa Barbara Museum of Art’s unveiling of Portrait of Mexico Today, a work acquired and placed on permanent display by the museum. Thousands attended the unveiling ceremony, and countless others have since visited to see the mural. Unquestionably that painting has enriched us all and contributed to the general prosperity of Santa Barbara. The fact that América Tropical is a more well known and significant work, indicates that its reinvigorated presence will no doubt render tremendous positive effects for the people and city of Los Angeles.

______________________________________

UPDATE: On August 8, 2006, I received the following e-mail from Peter Lincroft, the son of famed American muralist, Eva Cockcroft. Peter’s letter seemed an appropriate update to my original article:

“Excellent blog entry on the exciting news about America Tropical. In addition to its historical importance, the mural has a personal meaning for me, because it was the subject of the last mural ever painted by my mother, Eva Cockcroft, before she passed away on April 1, 1999. My mother’s mural, which she painted in collaboration with Alessandra Moctezuma, is in East LA and is a reproduction of (and tribute to) the original. You can get more info, as well as see pictures of the mural at this website.”

In addition, Eva Cockcroft wrote an essay titled Abstract Expressionism, Weapon of the Cold War, which was published in ArtForum magazine in 1974. In her article Cockcroft detailed how the US government supported abstract art in an effort to undermine Soviet “socialist realism.” Cockcroft’s essay may have led Frances Stonor Sanders to write The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters.