Summer of Love – Take 2

The first day of summer in 2017 was June 20, but the date also marked another occasion, that of the 50th Anniversary of the 1967 Summer of Love in San Francisco, California.

Remarkably enough in 1967 I passed though that Haight Ashbury scene as a wide-eyed, impressionable 14 year old, and what I saw there never left me. In fact the experience was so—you’ll forgive the expression, “mind blowing,” that it changed my life forever. Overall the 60’s experience remains a signpost on my life’s path, one that I intermittently come back to visit without succumbing to the most deadly of all diseases, nostalgia.

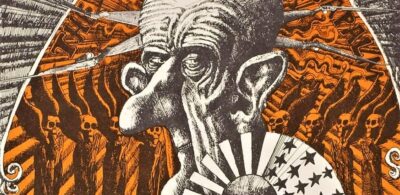

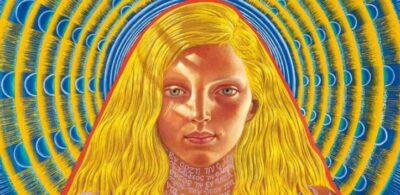

That psychedelic poster art played an enormous role in the hippie scene is undeniable, and aside from the incredible music associated with the movement, it’s the visual art that has left the most lasting impression.

While many are familiar with the posters and handbills that announced acid rock concerts at San Francisco’s Fillmore Auditorium and Avalon Ballroom, those works in no way represent the total output of psychedelic artists. Posters were also an influential method of communicating the movement’s ethics, moral principles, and political actions. The new visual language and typography of psychedelic posters promoted everything from anti-materialism and spiritual values to community festivals and antiwar protests.

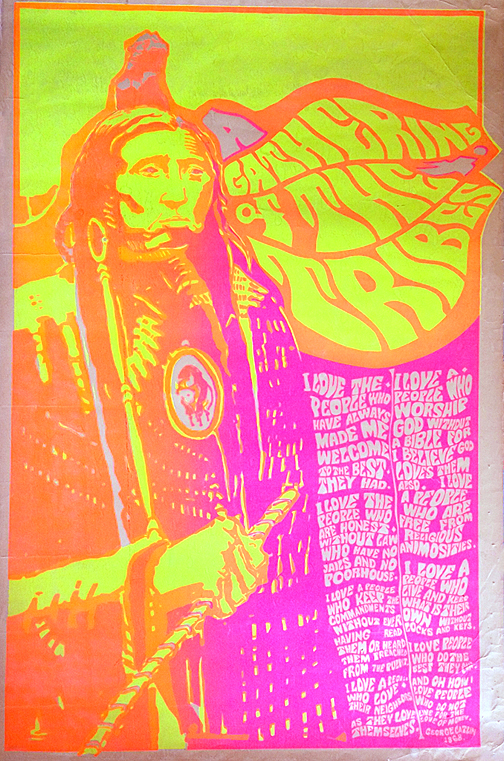

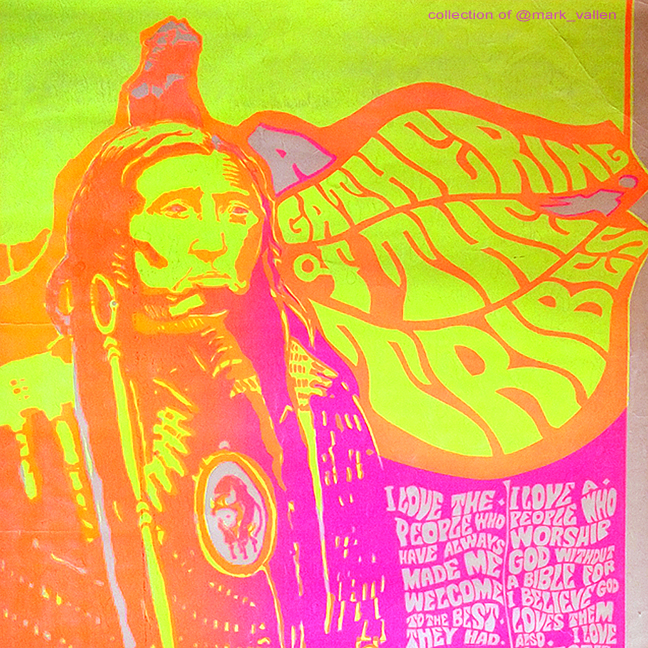

A good example of this would be one of the rare posters in my collection, A Gathering Of The Tribes, a split-screen serigraph printed in wild day-glow colors that celebrated Native Americans and their traditional way of life as an example for hippies to follow.

I can’t remember if I picked this gem up in Haight-Ashbury during the Summer of Love or if I acquired it soon thereafter, as the artist unfortunately left no signature or date on the print. Nevertheless, the poster is an outstanding example of psychedelic art and how such works were flavored with social protest and a questioning aesthetic. This particular poster used a 1868 quote by the painter of early Native Americans, George Catlin, as he described his encounters with indigenous tribes. In typical psychedelic fashion, the poster’s typography was psychedelicized and woven into the overall design. The quote reads:

I love the people who have always made me welcome to the best they had. I love the people who are honest without law—who have no jails and no poorhouse. I love a people who keep the commandments without ever having read them or heard them preached from the pulpit. I love a people who love their neighbors as they love themselves. I love a people who worship God without a bible for I believe God loves them also. I love a people who are free from religious animosities. I love a people who live and keep what is their own without lock and keys. I love a people who do the best they can—and oh how I love a people who do not live for the love of money.

Posters like this not only celebrated Native Americans, they suggested templates for alternative lifestyles and put people in touch with history. It was no small matter for me to have discovered the life and works of George Catlin through this poster, and I’m certain the print touched the lives of many others in equally profound ways.

Commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the Summer of Love, the de Young Museum in San Francisco offers The Summer of Love Experience: Art, Fashion, and Rock & Roll. The exhibition, which uses psychedelic posters, light shows, music, fashion, and film to explore the hippie counterculture, runs from April 8, 2017 to August 20, 2017.

Back in July of 2006, I wrote an article titled Art of the Psychedelic Era, an essay inspired by the Tate Modern in London and the Kunsthalle in Vienna having collaborated on mounting the major exhibition, Summer of Love: Art of the Psychedelic Era. That same exhibit traveled to America where it ran at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art from May 24, 2007 until September 16, 2007. A brief video of the Whitney’s “Summer of Love” exhibit can be seen on YouTube. In his review of the Whitney exhibit for the New York Times, art critic Holland Cotter offered the following comments regarding the incomplete and depoliticized nature of the show:

“The net effect is less to reveal a depth and variety of creativity than to demonstrate that the main function of alternative art was advertising, that the counterculture started as a commercial venture, which soon became a new mainstream and ended up an Austin Powers joke. Possibly this view represents the show’s critical edge, but if so, it is sharpened at the expense of accuracy. To many people who came of age between 1963 to 1972 political intensity was the defining feature of the period and its most interesting art. It never let up.

(….) Psychedelia and collectivity are back (and already on their way out again). But the revival is highly edited; a surface scraping; artificial, like a bottled fragrance. No one these days is thinking, ‘Turn on, drop out.’ Everyone is thinking, ‘How can I get into the game?’ The Whitney show, maybe without intending to, suggests that this was always true, and makes such an attitude seem inevitable and comprehensible. So, let’s have another ’60s show, an incomprehensible one, messier, stylistically hybrid, filled with different countercultures, and with many kinds of music and art, a show that makes the ‘Summer of Love’ what it really was: a brief interlude in a decade-long winter of creative discontent.”

I generally agreed with Cotter that the Summer of Love exhibit lacked scope and vision, and that other, “messier” exhibitions are in order. However, what’s really called for is not simply more art shows about rebellious times past, but a regeneration of the spirit that motivated the original participants during those exhilarating days. The actual Summer of Love represented not just “a brief interlude,” but a sharp and determined break with a conformist society. Every rule was examined, ignored or tossed by the wayside as people sought to create a more humane and rational way of living… an outlook we are in dire need of today.

Yes there was tragic excess and silliness in spades, and there’s no need to recreate any of that, but in 1967 people believed they could change the world for the better—and they acted accordingly, whereas today we have been gripped by a deep pessimism that is squeezing the life and humanity out of all of us. So yes, Mr. Cotter, “let’s have another ’60s show,” but let’s agree not to have this 21st century festival of life in some high and mighty museum… let’s have it in the streets.

2007 also marked the 40th anniversary of San Francisco’s Summer of Love, and a glimpse of those wild times was presented in a PBS American Experience documentary titled Summer of Love. Theodore Roszak, one of the many participants interviewed in the special, was in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district in 1967. A mover and shaker in the hippie scene and now a social critic and professor, Roszak summed up the Flower Power movement in the following way:

“I don’t think the Summer of Love left any blueprints behind on how to build a better world. It was much more a showcase for enjoyment, for happiness, for freedom, as people understood it then. But if you probe to the underlying values of displays like that, protests like that, you can perhaps see the seeds of a better social order than the one we’re living in now. If the ideals of the Sixties had prevailed, it would be a world, where people lived gently on the planet without the sense that they have to exploit nature or make war upon nature in order to find basic security. It would be a simpler way of life, less urban, less consumption-oriented, and much more concerned about spiritual values, about companionship, friendship, community.

Community was one of the great words of this period, getting together with other people, solving problems, enjoying one another’s company, sharing ideas, values, insights. And if that’s not what life is all about, if that’s not what the wealth is for, then we are definitely on the wrong path.”