Art of the Psychedelic Era

The UK Tate Gallery has mounted an exhibition titled, Summer of Love: Art of the Psychedelic Era, an exhibit that, “attempts to uncover this forgotten and repressed aesthetic that continues to exert an increasingly powerful influence on many contemporary artists.”

The Tate also developed an adjunct show on the aesthetics of psychedelia for the Kunsthalle in Vienna – both exhibits are running concurrently until September, 2006.

Having been a teenager in 1960s Los Angeles, I’m more than a little familiar with the art and culture presented in the groundbreaking Summer of Love exhibit, and I’m glad to see the genre finally receiving serious examination.

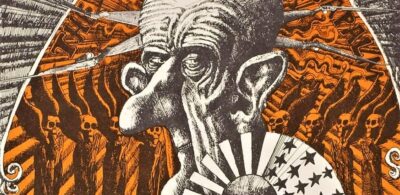

Most people associate psychedelic visual art with the Art Nouveau inspired day glow posters that announced Acid Rock concerts – and there’s no doubt psychedelia left a strong imprint on the music of the era.

Bands like Country Joe and the Fish and Jefferson Airplane exemplified the sound – but the aesthetic might best be summed up in the Beatle’s 1966 song, Tomorrow Never Knows, “Turn off your mind, relax and float down stream, it is not dying. (….) But listen to the color of your dreams, is it not living?” We have a fair record of 60s psychedelic music, but little serious attention has been paid to the visual arts of the period – until the Tate’s landmark examination.

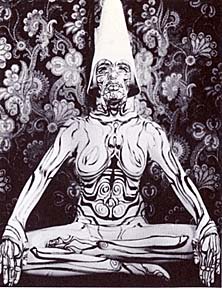

I won’t dwell on the thrills and excesses of the Psychedelic movement, that’s simply not within the scope of this essay. While some counter-culturalists advocated the ingesting of mind-altering psychoactive substances like LSD, mescaline, and peyote in order to achieve an “altered” or “expanded consciousness,” others promoted yoga and meditation to achieve the same end.

The point is, those seekers broke from mainstream culture, inspiring artists to create a psychedelic aesthetic that would impact the wider society.

Psychedelic artists left their mark on graphic design, typography, fashion, fine art, and invented new forms like light shows and “happenings,” the predecessor of performance art.

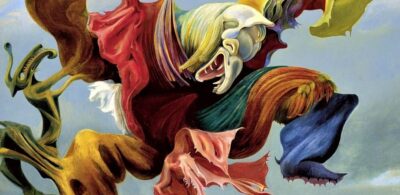

The Tate has produced an excellent catalog book for the exhibit that details all of this and more. I was most excited to learn the exhibit includes works by Ernst Fuchs and Abdul Mati Klarwein, painters I was fascinated by as a teenager, but the exhibit also includes works by Isaac Abrams, Richard Avedon, Robert Indiana, Andy Warhol and the only known watercolor created by Jimi Hendrix.

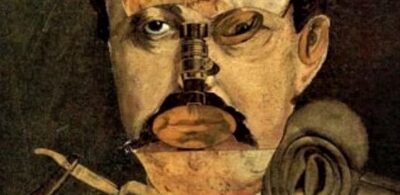

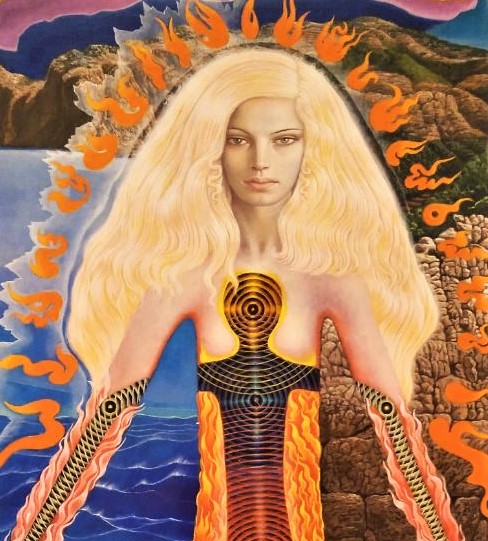

Ernst Fuchs founded the Vienna School of Fantastic Realism with fellow Viennese artists in 1948. Moving away from the radical surrealist idea of art springing from the unconscious mind, Fuchs thematically pursued a visionary mysticism buttressed by a technical virtuosity reminiscent of early Flemish painting. While Fuchs experimented with peyote during the late 1950’s, his hallucinatory artworks were already transcendent and terrifying, filled with luminous beings, mythological creatures, fantastic landscapes and vibrant colors.

Needless to say his works both inspired and attracted the attention of those artists who were fashioning the psychedelic art movement of the 1960’s, and the genre is near impossible to imagine without the far-reaching influence of Fuchs.

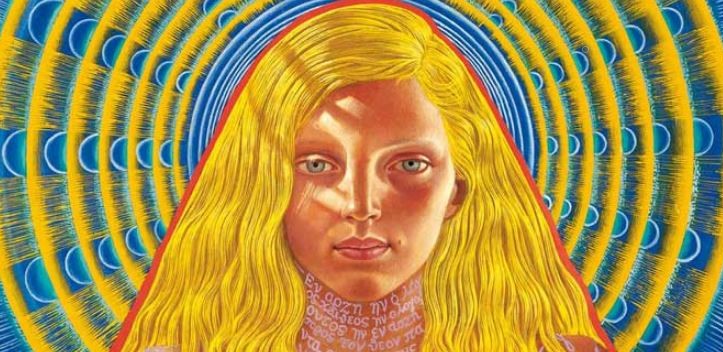

Abdul Mati Klarwein was taught the painting methods of the old masters by Ernst Fuchs, and Klarwein’s staggering psychedelic images graced the album covers of Miles Davis and Santana, bringing psychedelic aesthetics into the homes of millions.

Klarwein counted Jimi Hendrix and Timothy Leary among his close personal friends, with Leary advising the painter he didn’t need psychedelics to create his art.

“I painted psychedelically before I took psychedelics,” said Mati, “It’s like what Dali said, I don’t take drugs, I am drugs.” However, Klarwein’s paintings, like those of his fellow psychedelic artists, were spurned by the gallery system of the time. The Tate noted this was because the works “went entirely against the cool, literal tendencies of the period,” which says a lot about the gallery system past and present.

What we’ve been told about the Psychedelic movement up to this point is generally a load of crap, and it pains me to no end that such a vibrant and original school has been reduced to a handful of cheap, mocking and inaccurate clichés.

It’s wonderful that the Tate and Kunsthalle museums are making an effort at sorting out the Psychedelic movement, giving it some context and attempting to make some sense of it all, but voluminous studies are still needed to cover the wide range of psychedelic aesthetic practices and their motivations. In a time of manic consumerism and militarism, we might benefit from considering and understanding psychedelia’s messages concerning universal peace and love. These days, we could all use a bit of “expanded consciousness.”

_______________

UPDATE: Abdul Mati Klarwein, born 1932, passed away in Majorca, Spain on March 7, 2002. Klarwein was born in Hamburg, Germany to a Jewish father of Polish background and a German mother; when the Nazis seized power the three fled to Palestine. In the artist’s words: “I am only half German and only half Jewish with an Arab soul and a African heart.”

Ernst Fuchs died at the age of 85 on November 9, 2015. He died of old age, and left behind 16 children. His family remarked: “His optimism, spontaneity and generosity inspired generations of artists and friends and will always be remembered.”

Videographer James Kalm walked through the Summer of Love exhibit at the Whitney with a video camera, and his 10 minute film found at www.youtube.com captures some of the flavor of the show. Most notable in the video are the rooms displaying psychedelic lightshows, and a glimpse of the room-like shrine made from reproductions of paintings by Abdul Mati Klarwein. Kalm also visited New York’s Microcosm Gallery to videotape an exhibit of psychedelic paintings by Isaac Abrams.