The Death of Franklin Rosemont

Though he passed away last April, I feel compelled to note the death of the American surrealist artist, historian, author, poet, and activist, Franklin Rosemont (Oct. 2, 1943 – April 12, 2009). The few press accounts taking note of his passing wax lyrical about a colorful figure whose journey through the late 20th century put him in intimate contact with the counterculture of the U.S., from the radical Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) to the Beat poets and beyond. But Rosemont will surely be remembered for his role in familiarizing Americans with the actual founder of surrealism – the French poet André Breton.

On my bookshelf there are two works by Rosemont. The first being, What Is Surrealism?: Selected Writings What is Surrealism: Selected Writings of André Breton, a compilation of essays and theoretical writings from Breton that were brought together and first published by Rosemont in 1978. Already well versed in the tenets of the surrealist school, I acquired Rosemont’s tome the year of its publication, and reading it cover to cover was nothing less than revelatory. What is Surrealism is the antidote for all those suffering under the illusion that Salvador Dalí best exemplified the surrealist movement. No greater tribute to Rosemont can be offered than to quote from the foreword he wrote for What is Surrealism;

“I hope no one seriously expects surrealism to have any positive meaning except to those who are aware that the existing order cries out to be negated and transformed. That there is no solution to the decisive problems of human existence outside proletarian revolution is, for surrealism, a first principle that is beyond argument. Nothing would be more difficult than reconciling surrealism to bourgeois culture.

I know that everything continues normally today, as yesterday, as if life were an IOU punctuated now and then with a yawn, a shrug of the shoulders or a punch in the nose. Immobilized beneath a seemingly inflexible net of counterfeit hopes and fears – hopeless and fearless at the same time before a destiny that could hardly be more ruinous to the free development of the human personality – men and women go on fabricating illusory foresights and pitiful afterthoughts as if nothing more important were at stake than the price of cigarettes.

But in this grim charade, fortunately, nothing is foolproof. A split second is sufficient to say no, to let the lions escape, to open the wounds of reality, to stop the assembly line, to set out for the unknown. Accidents do happen. With surrealism the phoenix of anticipation emerges unfailingly from the ashes of everyday distraction, rising defiantly on wings of vitriol and amber, putting to shame the musty compromises that provide the glue with which the existing agony adheres to so many passing thoughts. Dispelling the mirage of futility, traversing the mirror of fatality, surrealism is resolved to stop at nothing.”

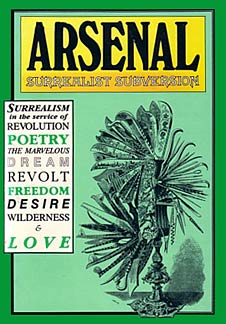

The other book by Franklin Rosemont that has a place in my library is an edition of ARSENAL: Surrealist Subversion, a compendium of surrealist poetry, art, diatribes, and histories published by Black Swan Press and edited by Rosemont. Whenever I crack open the large paperback brimming with bizarre dream-like graphics, nonsensical prose, and frenzied invective against “reality” – I am always heartened. I acquired this specific edition of the long running periodical when it was published in 1989, eighteen years after the first copy of ARSENAL made its appearance in print. While the journal is filled with ecstatic giddiness and lunacy, it is far from being frivolous, in fact it possesses the steely earnestness and intensity one expects from a revolutionary tract. Again, Rosemont’s own words best serve as his eulogy – these taken from “Now’s The Time”, the opening editorial he penned for the ’89 volume of ARSENAL;

“Most assuredly, if surrealism continues to develop it will be because surrealists continue to develop it. And even if every one of those who call themselves surrealists today threw in the towel, the fight would hardly be over. Surrealism’s questions, in any case, remain defiantly and even horribly open – the festering wounds all over the bloated body of christian-capitalist hypocrisy – and quite unphased by the would-be curative incantations of those whose job it is to reassure society’s self-appointed managers that surrealism, like working class emancipation, is safely obsolete.

Even were we to join the inane conformists’ chorus that sings surrealism’s death, it would make little difference, for those who resolve to pursue these questions must sooner of later discover for themselves that inevitably it lives again, albeit perhaps in forms not immediately apprehensible to the pontifically glib horn-tooters of total counter-revolution.

(….) Surrealism continues to advance today, and to make a difference, because it refuses to compromise with unfreedom, because it holds true to its own irreducibly wild and untamable means, outside all repressive frameworks. Anti-statist, anti-sexist, anti-racist, anti-religious, anti-anthropocentric, anti-academic, allergic to Western civilization and its values and institutions, surrealism passes with flying colors what John Muir, one of the greatest of American presurrealists, called the test of the wilderness. ‘And how do we reach this truly free society?’ Start by dreaming. Those who don’t know how to cross their bridges before they come to them will never get anywhere.”