Yue Minjun: Execution

At London’s Sotheby’s auction house on Oct. 12, 2007, just as Execution, a painting by contemporary Chinese artist Yue Minjun was about to go on the auction block, a man seated in the auction hall leapt to his feet and began shouting; “Shame on all of you! You’re spending millions of pounds on art and the world is falling apart! Shame on you!” Security personal quickly descended upon the man, escorting him off the premises as wealthy bidders applauded his eviction. CNN captured the disruption in its report on the London auction, which you can view on YouTube. It’s not hard to fathom the disorderly fellow’s complaint – moments later Minjun’s painting sold for $5,996,932 dollars.

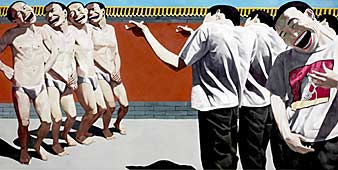

Art world gatekeepers have tapped Yue Minjun as the most important artist working in the People’s Republic of China today, which is no surprise considering his canvases are laden with the irony and cynicism so fashionable in postmodernist art. The artist’s unnerving paintings feature groups of men (in actuality Minjun’s self-portrait) with fixed, unvarying, grinning faces, who are obviously very lost in the new China. Privileged circles have christened Minjun’s art as “cynical realism”, and for Western art world elites who have long favored a ferocious pessimism over humanism, it is an especially apt term.

But it’s one thing for Western art world elites to be enamored of China’s “cynical realism”, and quite another for China’s communist authorities to accept it to the extent that they do. Minjun’s canvases quite openly mock the smiling workers of China’s now abandoned “Socialist Realism”, and his paintings most definitely convey the feeling that all is not well in the worker’s paradise. Undoubtedly the artists of China have been given a certain amount of leeway for experimentation in aesthetic matters – providing it does not lead to open criticism of the state, and some artists have even become millionaires in the process. In today’s China, “market reform” and an emphasis on getting rich have trumped the communist ideals of collectivity and classless egalitarianism. If the complexities, incongruities and stark contradictions surrounding China’s modern art have me stumped, then it surely must be an even larger conundrum for the Chinese themselves.

So what is behind the delirium and overheated feverish trade in modern Chinese art? In its Sept. 2007, article titled Cultural Evolution, Forbes magazine offered one response when it quoted art dealer Michael Goedhuis – who sells contemporary Chinese art at his galleries in Beijing, New York and London; “Just a few years ago this market was absolutely dormant, now it’s galloping. It’s an erratic market, but as more new buyers enter the bidding, the prices will shoot higher.” But that still leaves as an open question exactly why the Western market for art from the People’s Republic of China is “galloping”, and why there isn’t – for instance – an equivalent interest in the modern art being made in Cuba.

Are contemporary works of art from the People’s Republic of China really worth the outrageous sums of money currently being paid by Western collectors? For that matter, is any modern work of art from anywhere in the world actually worth that much cash? Apolitical collectors, investors and art world elites from the West have stepped into the most politicized of all arenas by purchasing art from communist China, all the while feigning ignorance of the fact that they are engaged in a political process. It goes without saying that these same people have little or no interest in realist painters from the West who offer social criticism through their art.

Yue Minjun’s Execution is undeniably a take on Goya’s famous, The Third of May, as well as being reminiscent of Edouard Manet’s, The Execution of Emperor Maximilian – both fervent observations on political violence. Minjun simply transposed his grinning men onto the background of Tiananmen Square, an obvious reference to the 1989 Tiananmen Square confrontation. But in his painting there are no student activists with passionate ideals, no soldiers bent on preserving the status quo, no hint at a clash of ideologies, there is no human story at all – just a howling emptiness where everything collapses into those vacuous grins.

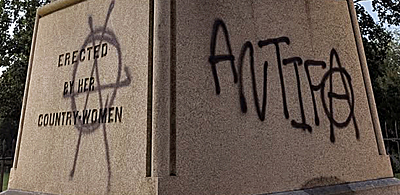

Yue Minjun created Execution in 1995 and sold it that same year to a private Chinese gallery for $5000. British stockbroker Trevor Simon purchased Minjun’s painting in 1996 for $32,000, when he found it hidden in the backroom of the Hong Kong gallery. Simon purchased the painting under the gallery’s stipulation that, in order to protect the artist from political persecution – the work not be exhibited or shown to anyone. Simon agreed, purchased the canvas, and then stored it in an English warehouse until selling it at the 2007 London Sotheby’s auction – the very first time the artwork had been seen in public.

The nearly $6 million paid for Execution is the highest price ever paid for a contemporary Chinese artwork. The purchase comes in the wake of the October 7th Hong Kong Sotheby’s sale of avant-garde Chinese art, where a different painting by Minjun, The Massacre at Chios, sold for $4.08 million, and works by other avant-garde Chinese artists fetched prices beyond the million dollar mark. Overall sales came to more than $42 million – a staggering sales record for modern Chinese art. At the October 13th auction at Phillips de Pury & Company in London, works from the Farber Collection of Chinese avant-garde art went up for bid. Wang Guangyi’s Great Criticism: Coca-Cola, part of a series of paintings by the artist combining Western corporate logos with imagery from the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, sold for $1.59 million.

If only the same influential art world leaders were as interested in the painters of “cynical realism” in the West.