The Enduring Works of Goya

Los Caprichos, the world-renown etchings by Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (1746-1828), are being displayed at the Cal State Fullerton Art Gallery in Fullerton, California, from November 1, 2008 through December 12, 2008. The exhibit is actually the tenth stop in a traveling national museum tour that began in 2005 and is slated to continue until 2010.

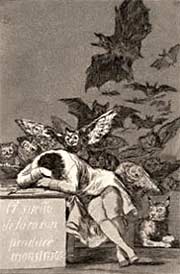

Privately published by Goya in 1799, the eighty celebrated prints of Los Caprichos (the Caprices), provide a dark and phantasmagorical depiction of the artist’s homeland during the Spanish Inquisition. Said by Goya to be a criticism of “human errors and vices”, the Los Caprichos etching suite reads like a fevered dream, full as it is with demonic looking creatures, prostitutes, and goblins – in addition to corrupt clergymen and oligarchs. If the foibles Los Caprichos depicted over two centuries ago seem familiar to us today, it is because Goya captured the eternal truth about how social divisions, economic crises, superstitions and erroneous beliefs can lead to mass psychosis – a condition we suffer from acutely in these postmodern times.

In July of this year a university student in England writing a dissertation on Goya, contacted me by e-mail to ask if I would be willing to answer a number of questions regarding the artist, his legacy, and the enduring influence of his works. I responded favorably to the request by writing the following observations, which, since others have similarly made inquiries concerning my thoughts on Goya – I have decided to publish here in part:

Q: In what way has Goya influenced you in your artwork and your views on war?

A: Goya was, and continues to be, an influence in my life and work. I first became aware of him when I was a mere child. Flipping through an art book I discovered Goya’s painting, Saturn Devouring His Son. It was an image that simultaneously horrified and intrigued me. Not being a sophisticated reader at the time, I could only imagine what the painting was supposed to signify.

[ Saturno Devorando a su Hijo (Saturn Devouring His Son) – Francisco Goya. Oil mural transferred to canvas. Created between 1819 and 1823. One of the so-called “black” paintings the artist created directly on the walls of his home outside of Madrid. This macabre image was located in Goya’s dining room. Museo del Prado, Madrid.]

Later on I rediscovered Goya, stumbling upon his nightmarish Los Caprichos series of etchings. Of course I became infatuated with him, and by the time I entered my teens I was well aware of the master’s Desastres de la Guerra (Disasters of War) etchings. At fifteen I already knew that I had no choice but to be an artist, and at the same age I also became an activist against the Vietnam war. It was Goya’s remarkable works that helped convinced me to trod the path of social commentary in art – and I haven’t looked back since.Q: Do you think that the Disasters of War etchings are impartial? Can you ever be impartial when using journalistic techniques to record disturbing images?

A: When it comes to opinions, I do not believe it is possible for anyone to be “impartial”. One must first ask the question, “where do opinions come from?”; and in today’s world of media management and manipulation, it is not difficult to conclude that popular views are manufactured. I do not know that things have ever been different, after all – the word “propaganda” is derived from Sacre Congregatio de Propaganda Fide, the office of the Vatican established in 1622 to advance the faith. We currently live in a corporate media saturated environment where monopolies present “sound bite” news that informs, or rather, misinforms the general public, so I do not see how it is possible to talk about journalism as an objective or impartial force – if indeed it ever was one.

Goya’s Disasters of War series of etchings was most decidedly not “impartial”, but why would anyone think it necessary for it to have been so? In 1808 Napoleon invaded Spain with only one thing in mind – conquest. Before Goya created his etchings, should he have first stopped to consider the humanity of the French imperialists – endeavoring to present both sides of the conflict with his artwork? Perhaps the notion of impartiality or objectivity is overvalued. Would it not be beyond the limits of decency to demand that “both sides of the story” be told when reporting on the Nazi’s persecution of the Jews? One could offer an examination of Nazi atrocities, but anything other than a purely subjective denunciation would be unthinkable.

[ El Tres de Mayo de 1808 (The Third of May, 1808) – Francisco Goya. 1814. The artist’s depiction of French occupation soldiers executing Spanish civilians. The English art historian Kenneth Clark referred to this painting as “the first great picture which can be called revolutionary in every sense of the word, in style, in subject, and in intention”. Museo del Prado, Madrid. ]Q: In my opinion, The Third of May works because Goya’s translation of the event supported the Spanish resistance movement against Napoleon’s army. Do you think that The Second of May is an inferior work of art because the civilians are armed?

A: Goya’s painting, The Third of May, is far easier for a contemporary audience to understand than is the companion piece, The Second of May. With the passing of time, only historians can decipher the particulars represented – and both paintings are heavy with historical import. However, The Third of May is an unmistakable depiction of political repression, making it an eternal image that plainly illustrates an atrocity committed by faceless soldiers against unarmed and defenseless prisoners. In that sense it is more accessible to a contemporary audience unfamiliar with the events portrayed.

[ El Dos de Mayo de 1808 (The Second of May, 1808) – Francisco Goya. 1814. The invasion of Spain by France in 1808 triggered an anti-colonial uprising amongst the Spanish citizenry. Goya painted the outbreak of the revolt in Madrid when the French army used Mamelukes (Mercenary Arab soldiers), to help repress the Spanish populace. Today the painting hangs alongside its companion piece, The Third of May, 1808, in Spain’s Museo del Prado.]

To a modern viewer ignorant of history, The Second of May appears to be nothing more than a vicious melee. However, in its day it was perhaps the more popular painting, and it certainly was well understood by viewers to be the depiction of Spanish patriots rising up against a cruel foreign invader. That the painting portrays armed Spanish patriots engaged in acts of violence does not make the work less important or effective, but one does need to know some history to fully appreciate the canvas.Liberty Leading the People, painted by the French artist Eugene Delacroix in 1830, portrays an armed populace in the middle of a violent revolutionary upheaval. They follow Liberty, a bare-breasted women clutching a rifle and the tri-colored banner of the nation. A romantic representation of the French Revolution of 1830, the canvas has also become an iconic portrayal of the radical democratic spirit – and the portrayal of people in arms has not made it less so.

Q: Why do you think that Jake and Dinos Chapman “defaced” a set of the Disasters of War prints? They say that their version of the Disasters highlight the inadequacy of art as a protest against war.

A: The Chapmans modifying prints from the Disasters of War series was not meant to bring about renewed interest in Goya, but to themselves; their prime motivation being to disparage the very idea of art as a moral force capable of challenging unjust wars and those who wage them. A cursory examination of history will underscore the undeniable fact that art has played an enormous role, not only in successfully building consensus for wars, but in maintaining and extolling them. I doubt that even the Chapmans would contest the veracity of this statement. If it is to be admitted that art and culture can help initiate war, then why is it so difficult to realize that art and culture has also effectively hindered it?

What the Chapman’s statement indicates, is not just their inability to grasp history, but also their enormous failure to understand the social forces and institutions that give rise to wars. The Chapmans are incapable of offering perceptive systemic critiques of society, but they are very useful indeed when it comes to dishing out hopelessness, despair, and the usual reactionary tripe about humanism being a blight. But then, perhaps I underestimate the Brothers Chapman. Conceivably they are cut from the same mold as the early Italian Futurists, whose leader, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, proclaimed; “We will glorify war – the world’s only hygiene.” I am certain Marinetti would have loved the Champman Brother’s “enhancement” of Goya’s antiwar etchings.

What I found particularly odious about the Chapman’s reworking of the Disasters of War, was that the gesture came about while the combined armed forces of the United States and the United Kingdom were involved in the unpopular military occupation of Iraq. In essence, the Chapman’s reworked etchings clearly proclaim that all protest is futile, so why bother.

One hundred and eighty years after his death, some have traced the modernist art movement back to the works of Francisco Goya – like art critic Robert Hughes, who called the Spanish master “the first modern artist”. Goya’s portentous works continue to reach out from his epoch to shed light on the horrors and follies of our own time. As a child in late 1950s Los Angeles, exposure to the works of Goya altered the course of my life. I am thrilled by the certainty of some young person walking into the Goya exhibit in Fullerton being similarly transformed.

Goya: Los Caprichos. November 1 – December 12, 2008, at the Cal State Fullerton Art Gallery in Fullerton, California. Opening Reception, Saturday, November 1, 5 to 8 p.m. (Gallery closed for Thanksgiving holiday). Directions to the Cal State Fullerton campus and its Main Art Gallery are available here.