Ward Kimball – Art Afterpieces

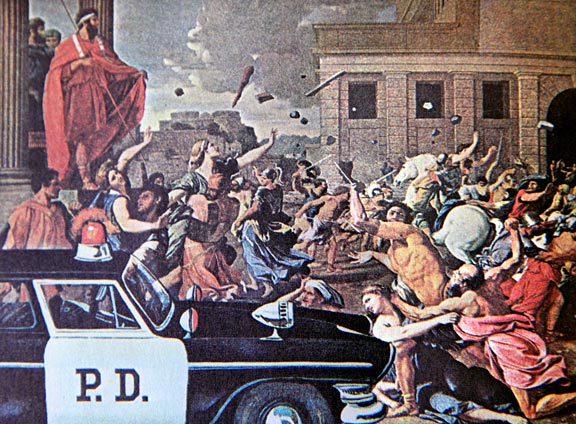

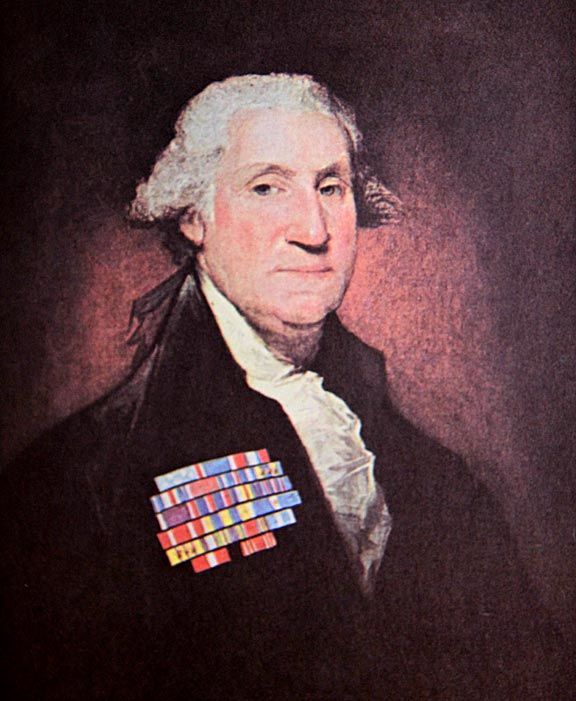

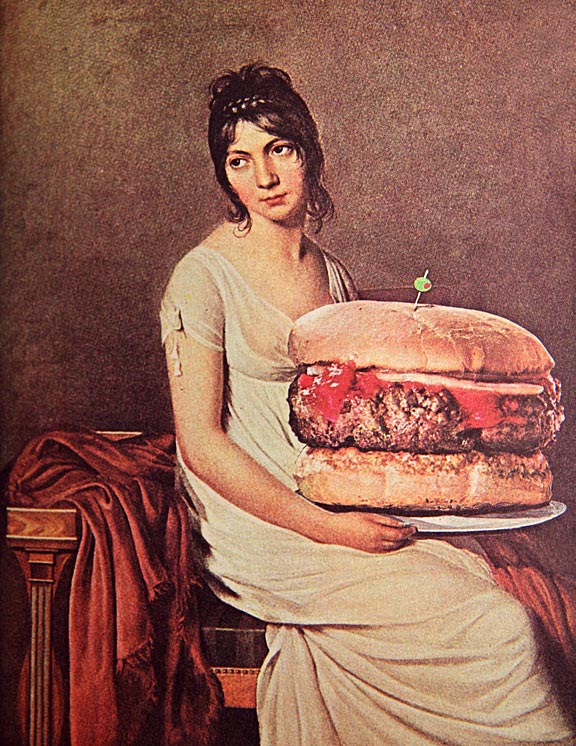

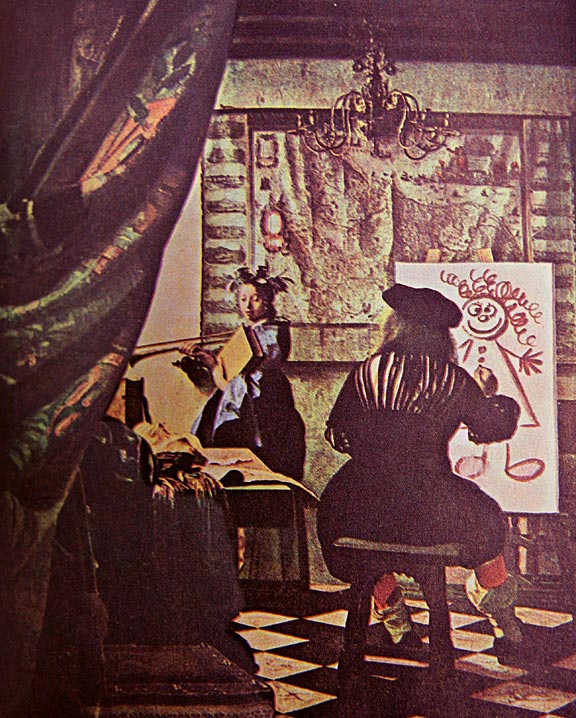

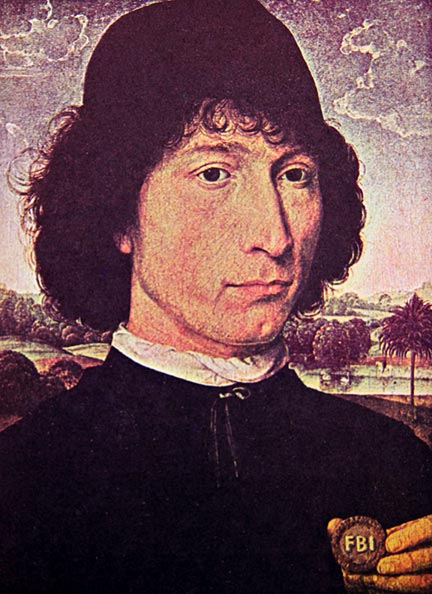

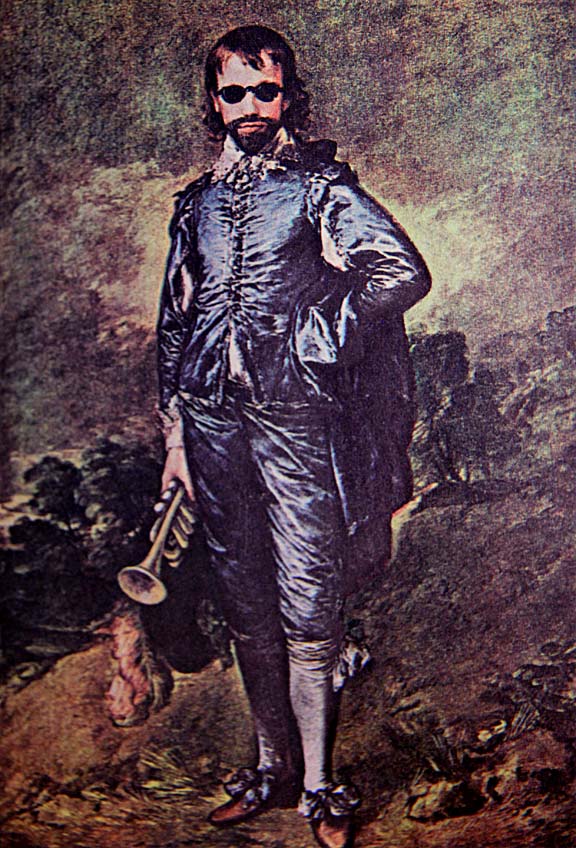

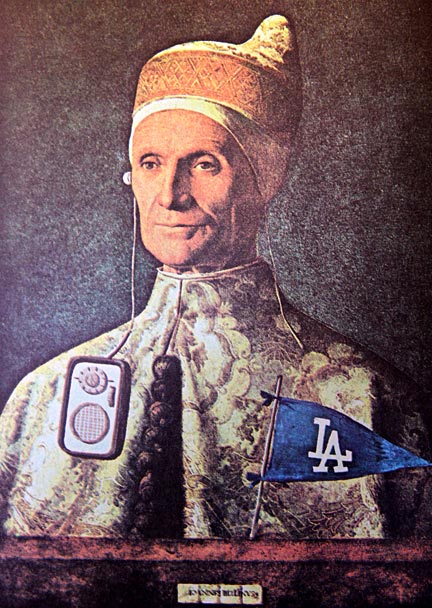

In the early 1960s, American artist Ward Kimball (1914-2002) began to playfully alter reproductions of Old Master paintings; he painted directly on the mass-produced replicate masterworks, substantially altering the prints by inserting a number of incongruous images, or sometimes only slightly changing the facsimiles by inserting the tiniest of details.

Kimball was a superb draftsman, caricaturist, and cartoonist employed by the Walt Disney Company from 1934 to 1972. He was known as one of Disney’s “nine old men,” that circle of senior artists and animators that were the major force in the animation division of Disney during its most inspired period. Kimball was responsible for creating or animating some of the best known Disney characters – Jiminy Cricket from Pinocchio and the Mad Hatter and the Cheshire Cat from Alice in Wonderland to name but a few. Kimball’s accomplishments for Disney Studios are legendary and much too long to list here, but he had many interests outside of that particular animation studio.

When not laboring on Disney projects, Kimball made mockingly sardonic statements on contemporary society with his ridiculous additions and edits to old master paintings. Kimball’s parodies included Gainsborough’s Blue Boy as a bearded Beatnik in dark sunglasses, and Vincent Van Gogh’s iconic sunflowers stuck into a vase that happened to be an empty VAT 69 Whisky bottle. More than a few of the altered images made comment on the hyper-consumerism that was voraciously engulfing the U.S., and some of Kimball’s works were pointedly political, most however were simply absurdist in nature.

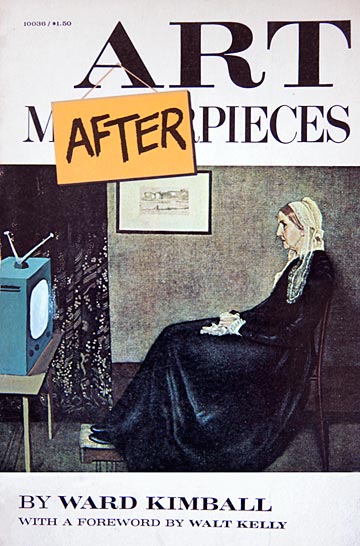

Kimball gathered together 60 of his best (some might say, worst) altered paintings and compiled them into a full-color humorous soft-cover booklet titled, Art Afterpieces. Of the artworks in the book, each was credited to the original artist and bore its original title. Kimball offered no pseudo-intellectual, mumbo-jumbo art theories to justify his indelicate comic works. They were, after all, created for a joke book.

Published in 1964 by Simon & Schuster, the little book of visual pranks became wildly popular in the U.S., flying off the shelves of stores across the nation. As a precocious 11 year old in 1964 I purchased my own brand new copy at a local dimestore for $1.50. The now yellowed and dog-eared original edition still has a place of honor in my book collection, and from it I have gleaned the illustrations presented in this article.

As a collection of sophomoric visuals, Art Afterpieces, while boorish and uncouth, also happened to be hilarious; no doubt even the most snobbishly cultured people at the time laughed at the book’s loutish humor while behind closed doors. Nevertheless, the book was never accepted as anything other than a cheap joke book for those who were eternally adolescent, no one took it seriously, and on no account was it ever looked upon as high art. In fact I am hard pressed to say that it was ever regarded as art at all – even by Mr. Kimball. The book proved so successful that it was reprinted in 1967, and again in 1980 (with a new foreword penned by comedian Jonathan Winters).

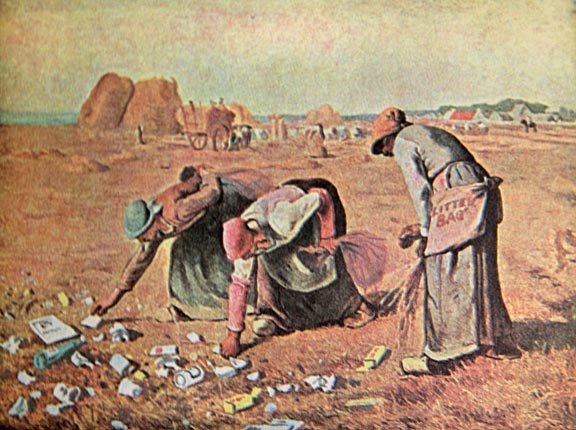

![The Gleaners - Jean-François Millet. Oil on canvas. "Des Glaneuses" (The Gleaners) - Jean-François Millet. Oil on canvas. 1857. [1]](https://b3060046.smushcdn.com/3060046/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/2_millet_the_gleaners.jpg?lossy=0&strip=0&webp=1)

“When I was a young problem child I used to get sent to the principal’s office to catch hell for such things as melting holes in the celluloid pencil sharpener with a magnifying glass or changing a chicken’s egg to a baseball on the teacher’s blackboard drawing. One day while I sat in the principal’s outer office awaiting my turn (I wasn’t the only bad guy), I got to studying a reproduction of Millet’s famous painting, ‘The Gleaners.‘ You know, the one that shows some European peasant women bending over the ground picking up what appears to be exactly nothing.

I soon got hip to how it feels to keep bending over and picking things up. My punishment for my misbehavior in the classroom was to spend an hour each day for a week picking up paper and trash from the schoolyard. This must have left a scar, for as the years roared by, every time I saw ‘The Gleaners‘ I wanted them to be picking up the trash. Then one day it happened. I had some paint left over, and in a matter of minutes Millet’s peasants were busy earning their salt cleaning up discarded beer cans and film boxes. That’s how Art Afterpieces got started, if you want to know.”

It is more than likely that readers of this web log have heard of the U.K. “guerrilla artist” who goes by the nom de guerre of Banksy; but is anyone familiar with Kimball? Why Banksy is widely celebrated and Kimball unheard of outside of certain quarters says a lot about today’s celebrity driven elite art world and who it selects to be groomed and promoted as an “art star.” In the summer of 2009, the Bristol museum in London mounted an exhibit of over 100 works by the pseudo-anonymous Banksy. A number of the works shown were his so-called “subverted paintings,” modified reproductions of famous masterpieces that had been painted upon or otherwise edited by Banksy. The paintings have time and again been hailed as ingenious, original, even revolutionary, but when first seeing them all I could think of was Ward Kimball’s Art Afterpieces.

When Banksy exhibited his version of The Gleaners (renamed the Agency Job) at the Bristol museum, was it a reworked Millet or a modified Ward Kimball? Certainly no one mentioned Kimball; it is fair to assume that everyone thought Agency Job was another of Banksy’s spoofs made at the expense of the art world… without knowing that Kimball had delivered the joke 45-years earlier, and with the same Millet painting!

Banksy’s approach is certainly not an homage to Kimball, that would necessitate acknowledging the influential artist by name and admitting owing a debt to his rare talent.

I think that in all probability Banksy was familiar with Kimball’s The Gleaners, and that he was counting on his audience not having that same familiarity.

In fact, the process Kimball once used to innocently alter the art compiled in his dimestore joke book of despoiled masterworks has now become a de rigueur practice for much of the postmodern art establishment, except that no one dare breathe the name of Ward Kimball.

Why does no one speak of Kimball? Ignorance of his life and work has much to do with it, but it is more a case of not wanting to let the “cat out of the bag,” seeing as how Kimball’s attitude about his artworks in Art Afterpieces blows the theoretical cover off of postmodernism. He simply did not think his altered paintings were important, and he offered no haughty theories to justify them. To Kimball his paintings were simply a joke.

Postmodern artists that “appropriate” the works of others while justifying their acts with lofty sounding gobbledygook, might think they have inherited Kimball’s legacy, but his altered reproductions were not meant to be exhibited in museums and galleries, purchased by billionaires for hundreds of thousands if not millions of dollars, or endlessly discussed by art snobs.

The renowned cartoonist Walt Kelly (1913-1973) wrote the foreword to Kimball’s Art Afterpieces. Kelly befriended Kimball when the two worked together as artists and animators at Disney Studios starting in the mid-1930s.

A genius in his own right, Kelly is today generally regarded as the originator of the modern comic strip because of his innovative cartoon creation, Pogo.

In his foreword Kelly properly situated Art Afterpieces in the tradition of published farce; the introduction is reprinted here in its entirety:

“It is correct, we believe, to claim that Mr. Kimball’s addenda, as they are collected in this volume, are original. The Parisian school of underground poster art says flatly, ‘Vive le moustache!’ This group, claiming to be unique, has in fact produced nothing more than the additives of the mustache, the scrawl of eyeglasses, and occasional monocle (inevitably lopsided), and, if the viewer is lucky, he is treated to a blacked-out tooth in a creamy smile.

Then there are the hackneyed efforts of the imitative American alteration group, the so-called Subway Atelier in New York City. True, these monsters have made use of the added four-letter word across the faces of some of their subjects, but this is merely potential juvenile delinquency and to be classed with the accidental banjo-work of a messy monkey armed with a melting chocolate bar.

Now from the west rises a Lochinvar who is apparently a distinct cut above the messy monkey. In a talk with him this critic learned that Mr. Kimball, a youth of fifty, was disturbed about the publisher’s estimate that his work was ‘unfailingly funny.’ According to Mr. Kimball, if his work is funny, it has failed. ‘Cheen Crimes!’ exclaimed Mr. Kimball, his mouth full of melted chocolate bar, ‘this stuff is a lot deeper than they realize. It gets me right about here,’ he added, putting his hand to his throat.

For the fact of the matter is that Mr. Kimball is a master finisher. He finishes what others have started. Any bull can charge into a china shop, but the bull in this book ENDS the job.”

In praising Kimball’s works, Kelly aimed one of his typically droll remarks at Marcel Duchamp and his circle, accusing them in a tongue and cheek manner of having been poseurs “claiming to be unique.”

Kelly implied that any of Kimball’s altered masterpieces had to be more sophisticated than Duchamp’s feeble gesture of scrawling a moustache on a post-card sized reproduction of the Mona Lisa, and after viewing Kimball’s altered masterworks in this article, who can disagree with Kelly’s inference?

So why then are Kimball’s paintings not included in the collections of postmodern works currently held by today’s museums?

Kelly went on to lampoon “the so-called Subway Atelier in New York City” as pretenders to the throne of artistic genius. His reference to graffiti writers or the “American alteration group” as he put it, is instructive for two reasons. When his foreword was written in 1964 everyone understood graffiti to be the artless defacement of public property, this was accepted even by those making the graffiti, so Kelly was implying in a humorous way that Kimball was only slightly more talented than the hooligans that scrawled on subway walls.

But not even Kelly’s perceptive outlook and steely skepticism could have prepared him for the day when those “messy monkeys armed with melting chocolate bars” would actually be seated at the pinnacle of the elite art world.

I never forgot Kimball’s Art Afterpieces, though it seems the rest of the world did. Searching online for evidence of the book’s existence turns up almost nothing, scarcely even a mention.

More baffling is Kimball’s persona non grata status in the elite art world, where kitsch aesthetics are all the rage and lowbrow art regularly, if mystifyingly, fetches astronomical prices.

Today’s museum curators, gallery directors, arts writers, critics, art historians, and wealthy art collectors pay no attention to Kimball, but I say, give credit where credit is due.

At the time of its publication Art Afterpieces was a kitsch joke book that no one attached any importance to, least of all Kimball. Art world gatekeepers have since invented the theories that could be used – if they were so inclined – to describe Kimball’s works. He might be depicted as an “appropriation artist” that “deconstructed accepted boundaries” through the use of “ironic repurposed imagery.” With enough of that kind of regularly appearing hype, Kimball, even from the great beyond, could be transformed into an international art star.

Still, I think his avenging spirit, with melting chocolate bars in hand, would most likely come after those responsible for his deification.