Frida Kahlo’s 100th birthday

To celebrate the 100th birthday of artist Frida Kahlo, which falls on July 6th, 2007, Mexico’s Palacio de Bellas Artes (Palace of Fine Arts) is exhibiting the largest body of Kahlo’s artworks ever to be put on public display anywhere in the world.

Opening June 13th, 2007 and running until August 19th, 2007, the show is the first comprehensive exhibit of the artist’s works to be held in Mexico, and it’s comprised of some 354 original drawings and paintings – as well as a portion of Kahlo’s manuscripts and letters.

In addition, talks on Kahlo’s political views and influence on the arts will be held in conjunction with the exhibit. The Associate Press quoted Bellas Artes Director Roxana Gonzalez as saying, “It is important for our visitors to know that Frida wrote, thought – challenged the Americans – here they will see the complete Frida.”

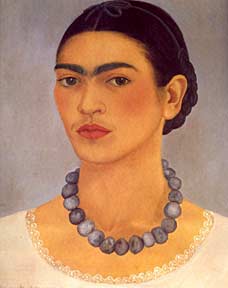

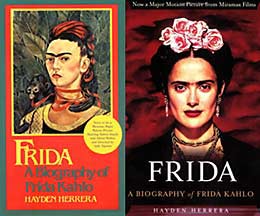

And that complete view of Frida is long overdue, especially here in the United States, where “Fridamania” has refashioned the radical artist into a series of harmless and exotic clichés. In Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo, author Hayden Herrera wrote that the artist became, “first a legend, then a myth and now a cult figure.” The end of that statement is most certainly true, and Herrera played no small role in the transformation of Kahlo into a pop icon – her 1983 biography served as the basis for director Julie Taymor’s 2002 Frida, starring Salma Hayek as Kahlo. Unfortunately that film has become the prevailing English-language history of the left-wing painter.

In an interview conducted for PBS by filmmaker Amy Stechler (The Life and Times of Frida Kahlo), Herrera was asked when people started to recognize Frida as a painter, and she responded by saying:

“In the second half of the seventies, she was not really very well known. In Mexico, she was known as Diego Rivera’s sort of peculiar wife with the strange little paintings that most people really didn’t like very much. They were too peculiar. And too weird.

They are weird. I mean, we’ve gotten used to them now, but they still are kind of weird. And in the United States, I don’t think many people had heard of her. At least, I’d never heard of her until somebody…Max Kozlov and Joyce Kozlov presented me with a catalog and said, ‘Go write about it for Art Forum.’ And that was about, I think around 1974, ’74, ’75… somewhere in there. Anyway, I think Frida Kahlo’s fame began in the late ’70s and had a lot to do with feminism, had a lot to do with the Chicana people in the United States loving having this sort of emblem of Mexicanidad and loving her whole story, because it’s a painful one.”

As a devotee of Kahlo, Herrera’s observations as quoted above are on target, but what exactly is she telling us? That the reasons for Kahlo’s fame have less to do with her abilities as an artist and more to do with the sensibilities of a contemporary audience? That’s quite a revealing statement regarding the cult of personality that has developed around Kahlo, which seems to have more to do with her tragic personal life than with her actual artistic output. When Herrera admits that Kahlo is understood as “myth” and “cult figure,” we’ve already slipped into territory where anything about the artist will be believed, which is undeniably why the Taymor/Hayek version of Kahlo’s life was so popular in the United States. The superficial film provided its audience with an easy to digest soap opera that focused on the sex lives and marital problems of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo – it was a movie that for all intents and purposes effectively stripped Kahlo of her political beliefs.

I’ve enjoyed the art of Frida Kahlo ever since the early 1970’s, but I find it astonishing that she’s now perceived, at least outside of Mexico, as that country’s leading artist, while her compatriots in the Mexican Muralist Movement have largely been excised from history.

To gauge the depth and breadth of “Fridamania” and how quickly the phenomenon took over, one need only examine the 1988 PBS American Masters documentary about her husband, Rivera in America, which detailed the art and career of the eminent painter.

Though you do catch glimpses of Kahlo in the documentary, the hour-long film barely mentioned her, and instead focused on the achievements of Rivera – who played an enormous role in changing the face of his nation’s art and culture. Today that portrayal has been entirely reversed, with Kahlo the super-star in the limelight and Diego left forgotten.

I don’t mean to imply that Kahlo doesn’t deserve acknowledgment or that she should be thrown back into obscurity. Personally I love her art and recognize her as an inspiring painter. But the passing of time should bring about a deeper appreciation of artists and art movements once misunderstood, and while time has no doubt been good to Frida Kahlo – why have the extraordinary artists surrounding her been retired to the shadows?

It has been relatively easy to commodify Kahlo’s works over the likes of those by fellow radical painters Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, Jean Charlot, Pablo O’ Higgins, Juan O’ Gorman and others. But it’s a mistake to view these didactic artists as “political” while maintaining Kahlo’s paintings were simply “personal.” Kahlo’s works are the perfect example of “the personal being the political.” No less than the founder of Surrealism, André Breton, recognized this fact. He famously said that “The art of Frida Kahlo is a ribbon around a bomb.”

A militant but unorthodox communist, Kahlo was connected to the major political events of her day.

Whatever one makes of her politics, ideology was undeniably a major force that consistently ran through her life, so I find it annoying that her persona has been recast to fit the current liberal intellectual atmosphere.

While big money and fan worship have airbrushed Kahlo into an easily digestible, exotic commodity, the truth can be found elsewhere. As fate would have it, an exciting new discovery has been made that re-emphasizes the undying loyalty and closeness between Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo.

The Mexican paper, La Jornada, reports that scientists in Mexico City have found over 100 hitherto unknown drawings created by the couple.

The artworks, along with photos and letters, were secreted away in a hidden room of the Casa Azul (Blue House), the house where the two artists once lived together and which now functions as The Frida Kahlo Museum. A special press conference has been arranged for June 27th, where a list of the exact items found will be revealed.

Frida Kahlo sought to sweep away the cobwebs of the old world, and perhaps the major exhibit at Mexico’s Palacio de Bellas Artes will shed some much needed light on that reality.