Charles White: Let The Light Enter

In April of 1967 the Heritage Gallery of Los Angeles published Images of Dignity, a monograph on the life and work of the great African American artist Charles White (1918-1979). I acquired a copy of the book just a year later when I was fifteen-years-old, the hardback volume providing one of my first insights into the works of White, American social realism, and the very idea of political engagement in modern American art. I have no hesitation in crediting White as a major influence in my life as an artist.

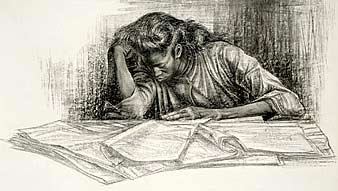

Opening this past January 10, and running until March 7, 2009, New York’s Michael Rosenfeld Gallery presents the important retrospective – Charles White: Let The Light Enter, Major Drawings, 1942-1970. The gallery’s biography on White opens with the following quote from the artist, which makes clear why he was such an influence upon me and why I continue to hold him in such high esteem:

“I am interested in the social, even the propaganda, angle in painting; but I feel that the job of everyone in a creative field is to picture the whole scene. . . I am interested in creating a style that is much more powerful, that will take in the technical end and at the same time will say what I have to say. Paint is the only weapon I have with which to fight what I resent. If I could write, I would write about it. If I could talk, I would talk about it. Since I paint, I must paint about it.”

I will mostly dispense with listing the biographical details and accomplishments of Mr. White since the artist himself wrote eloquently of his life and times in an autobiography that now appears on the Charles White Archive website. Instead I am going to focus on two aspects of White’s career that have considerable relevance to the present: his relationship to the Works Progress Administration in the U.S. during the Depression Era, and his connection to the socially conscious Mexican Muralist Movement of the same period – which has been another source of endless inspiration for me. In light of discussions on the possibility of there being a new federal arts program under the Obama administration, White’s overwhelmingly positive experience with the WPA provides food for thought, as does his having found common cause with the Mexican school of socially engaged art.

White was a 20-year-old living in Chicago, Illinois, when in 1938 he was employed by the Works Progress Administration and its Federal Art Project (FAP) Easel Painting Division, which was no small matter since until that time the young artist barely managed to survive by doing odd jobs – when he could find them. In a 1965 oral history interview conducted for the Smithsonian Institute’s Archives of American Art, White credited the FAP program with having enabled him to survive as an artist through very hard times. He also recognized the program for having expanded his range of artistic skills and knowledge, commenting that the FAP was “almost a school.” White said the following in his autobiography concerning having worked in the FAP:

“Looking back at my three years on the project, I see it was a tremendous step for me to be able to paint full time, be paid for it, although the pay was the bare minimum of unemployment relief. The most wonderful thing for me was the feeling of cooperation with other artists, of mutual help instead of competitiveness, and of cooperation between the artists and the people. It was in line with what I had always hoped to do as an artist, namely paint things pertaining to the real everyday life of people, and for them to see and enjoy. It was also a thrill for me to see so many accomplished artists at work, and to be able to learn from them.”

White eventually switched from the FAP’s Easel Division to its Mural Department, where he learned the basic skills needed to create monumental mural works. In 1939 FAP gave White the responsibility of creating a large mural for the Chicago Public Library. He chose for his mural the theme of outstanding African American leaders, and so painted Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass, George Washington Carver, Marian Anderson, and Booker T. Washington. Today the 5’ x 12’ oil on canvas mural hangs in the Law Library of the Howard University School of Law in Washington, D.C. Creating murals was a lifelong passion for White, and my home city of Los Angeles is blessed with the very last one he painted – a work produced in 1978 and located at the Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune Exposition Park Branch of the L.A. Public Library.

Here it is necessary to mention White’s relationship to the Mexican school – that fusion of muralism, printmaking, and easel painting driven by social concerns. “Los Tres Grandes”, the three greats of Mexican mural painting: José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, had all visited the United States by the early 1930’s. In the wake of their U.S. visits they left behind a number of fabulous public murals, but also an enthusiastic network of American artists they had influenced through workshops, lectures, collaborations, and direct mentoring.

In 1941 White met and married Elizabeth Catlett, a remarkable artist in her own right. The two traveled to Mexico City in 1946, where they created prints with El Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP – Popular Graphic Arts Workshop, founded in 1937), the foremost print collective in the country at the time. It was at the TGP that White learned the art of lithography, which became an enduring passion for him. At the workshop he met and worked with the likes of Diego Rivera, Pablo O’Higgins, and Leopoldo Méndez. In White’s own words, “One of the honors of which I am most proud is that of having been elected an honorary member of the Taller.” Catlett also did several of her most memorable prints while working at the TGP; and some of the collective’s prints, including works by Catlett and Méndez, made their way into Gouge – the Los Angeles Hammer Museum’s stunning exhibit on printmaking in the 20th century (now showing until Feb. 8, 2009).

During their sojourn in Mexico City, White and Catlett were invited to stay at the home of David Alfaro Siqueiros, where they lodged in the top floor of the muralist’s residence. White’s time in Mexico was revelatory, providing him the confirmation that his chosen path in art was the correct one to take. He felt kinship with the radical populism of the Mexican artists, whose fiery works embodied the very idea of social realism in art. White and Catlett would divorce in 1948: she stayed in Mexico for good, while he moved to New York City. There he began to associate with like-minded artists such as Antonio Frasconi, Leonard Baskin, Philip Evergood, William Gropper, Moses and Raphael Soyer, and other giants in American social realism. Eventually Mr. White settled in the city of Los Angeles, where he became an influential drawing teacher at Otis Art Institute.

What I always found so impressive about White was that he never abandoned his artistic vision in order to follow the dictates of what was fashionable. Despite the ascendancy and near total dominance of abstract art in the 1950s, followed by the successions of Pop, Minimalism, and all the vacuities of Postmodernism – White remained true to his style of figurative social realism. Part of his memoirs recount his lonely isolated struggle in the 50s against abstraction, of “going against the tide of what everyone was claiming to be ‘new’ and ‘the future'”, and we are all the richer for White’s perseverance.

But White’s courage went far beyond his flying in the face of what was trendy in the art world. He came to reject careerism in art, regarding celebrity as anathema to the higher ideals of art. The spirit found in the following passage of his memoirs should be held aloft as a banner by those artists and their supporters who ardently believe in art as a tool for social transformation;

“I no longer have my hopes and aspirations tied up with becoming a ‘success’ in the market sense. I have had a measure of success in exhibits, some prizes and awards, although not as much as I might have gotten had there not been certain ‘difficulties’ presented by my speaking as part of the Negro people and the working class. Getting a marketplace success or recognition by art connoisseurs is no longer my major concern as an artist. My major concern is to get my work before common, ordinary people; for me to be accepted as a spokesman for my people; for my work to portray them better, and to be rich and meaningful to them. A work of art was meant to belong to people, not to be a single person’s private possession. Art should take its place as one of the necessities of life, like food, clothing and shelter.”

Charles White: Let The Light Enter, Major Drawings, 1942-1970, at the Michael Rosenfeld Gallery. January 10 – March 7, 2009.