Sandinista Silkscreen Print

It was in 1984 that I originally carved the linoleum block from which I would pull the black and white print titled, Sandinista. In 1986 I reworked the block print into a full nine-color silkscreen print. I hand-pulled an edition on the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Augusto César Sandino, the legendary Nicaraguan leader who was murdered Feb. 21, 1934.

In reality I never offered the prints for sale. Over the years I misplaced my suite of serigraphic Sandinista prints. I’m sure to find them buried in my studio somewhere, and when I discover them they’ll be available for purchase.

Just who was Augusto César Sandino, the man the Sandinistas took their name from? My interest in him began in the early 1970s, when I commenced serious study of Latin American history and found out that he was a celebrated figure in Nicaragua and throughout Latin America. Even to this day he is often compared to Simón Bolívar and referred to as the “General de los hombres libres” (General of free men).

In the United States during the late 1920s, Sandino was villainized and condemned as a “bandit,” but by the late 1930s he was almost entirely forgotten in the US. Augusto César Sandino should be remembered as one who dreamt of, and fought for, a Latin America that was free, sovereign, and independent.

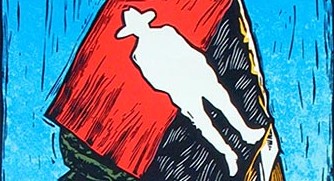

By the late 20th century in Nicaragua, Sandino’s visage had been transformed into a popular, almost ubiquitous symbol of freedom. His silhouette was immediately recognizable to all, and the ten gallon hat that he wore in the 1930s became an ever-present symbol. This short-hand language of rebellion was to become so conceptually abstract that by the time of the 1979 revolution Sandino’s portrait was rarely seen: instead, minimalist and highly stylized depictions of his hat were etched or spray painted onto surfaces everywhere. Likewise, Sandino’s commanding silhouette was carved, daubed, and spray painted onto every available surface.

In my silkscreen print I portrayed an anonymous individual waving a flag marked with a silhouette of Sandino, his faceless outline a ghost that will forever haunt tyrants and invaders. It should be noted that in 1980 the UK punk band The Clash, popularized Sandino and Sandinismo with their three record album release titled Sandinista!

Augusto César Sandino was born May 18, 1895, in Nicaragua’s Masaya province, but his story actually began with the interventionist foreign policy of the United States. The US was interested in Nicaragua as a potential site for a canal linking the Pacific to the Atlantic Ocean, expanding trade routes and extending US control over the entire region. In order to guarantee that Nicaragua would remain under its domination, the US directly intervened in the country several times starting in 1909. In 1912, Washington sent thousands of troops to wipe out a nationalist uprising, the beginning of a military occupation that continued until 1933.

When civil war broke out between Nicaraguan liberals and conservatives in 1926, Sandino joined and fought on the side of the liberals. In 1927 the US intervened on the side of the conservatives “in order to protect US citizens.” Initially landing some 5,000 U.S. soldiers in the city of Corinto, the Yanks then bombed the liberal-held city of Chinandega by airplane, it would be the very first air attack in US military history to be conducted against a civilian population center.

Liberal politicians and generals surrendered to the US backed conservatives that same year, and Washington sent 800 more Marines to support the new regime, but Sandino refused to surrender. From his mountain jungle hideaway he issued a July 1st manifesto that read in part:

“My greatest honor is to have come up from the ranks of the oppressed, who are the heart and soul of our people. We have been at the mercy of those hired assassins who helped foment high treason: the Conservatives of Nicaragua who have destroyed the nation’s dream of freedom and relentlessly persecuted us as if we were not the sons and daughters of the same country.

I accept the challenge to fight, and I myself am ready to initiate the struggle. My answer to the cowardly invaders and traitors to our country is my battle cry. My body and those of my soldiers will form walls against which the legions of Nicaragua’s enemies will be dashed to pieces.”

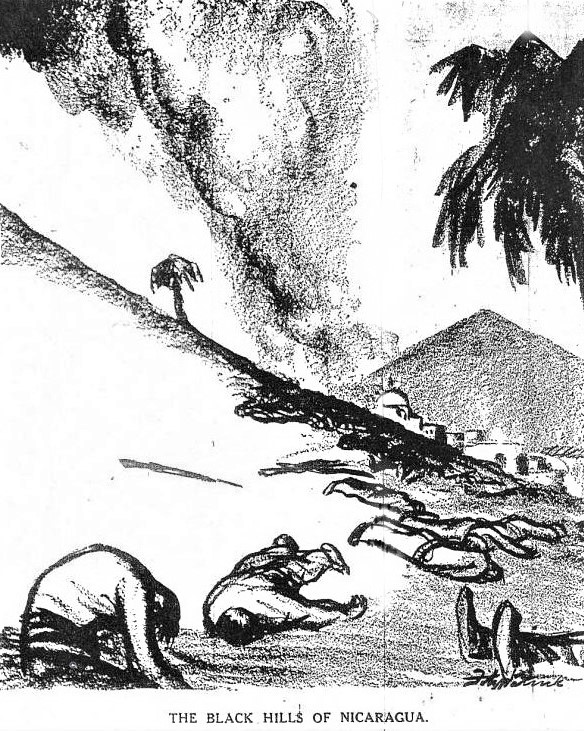

On July 16, 1927, the US again used airpower against Nicaraguans, this time dropping bombs on Sandino’s forces in the city of Ocotal. It was another aviation first, the earliest known instance of US ground forces directing an air attack. Five US Marine biplanes managed to kill some 300 people, according to press accounts at the time.

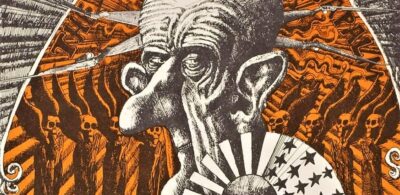

Newspaper editorial cartoons around the world expressed outrage and dismay over the carnage being inflicted by the US air war. Soon after the air attacks, the US worked with its client government in the capital of Managua on the creation of the National Guard, Nicaraguan troops that would be trained, armed, financed, and directed by US commanders.

In a March 28, 1928 article titled Expect Long Stay for Marines, the New York Times wrote about a comment then Secretary of State Charles E. Hughes made concerning the US occupation of Nicaragua:

“Notwithstanding that Charles E. Hughes is quoted here as declaring at the recent Pan-American conference at Havana that the marines would be withdrawn from Nicaragua at the earliest possible time, it is improbable that any responsible person here believes they can be withdrawn for many months, perhaps for years, to come. The Nicaraguans themselves, Conservative and Liberals alike, declare unreservedly that anarchy would descend on the country again if the United States withdrew its forces.”

In November of 1932 Juan Bautista Sacasa won Nicaragua’s presidential election, and Sandino agreed to peace talks with Sacasa’s government. The US Marines finally withdrew from the country in 1933, leaving their well trained and armed surrogates, the National Guard, to preserve order.

On February 21, 1934, General Sandino, his father, and three aids were driven to President Sacasa’s home for dinner. By order of Anastasio Somoza García, head of the National Guard, Sandino and his party were seized by Guardsmen, taken to an open field, and fatally shot. Two years later Somoza overthrew the government of Sacasa and declared himself leader of the country. The US government did not break diplomatic relations with Somoza’s regime, preferring instead to support military dictatorship in Nicaragua for the next four decades.

The poet Rigoberto Lopez Perez assassinated Somoza in 1956, but power was immediately transferred to Somoza’s eldest son, Luis Somoza Debayle. In 1961 nationalists and left-wing activists rallied behind the legacy of Augusto César Sandino to establish the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional (FSLN), or the Sandinista National Liberation Front. Their intent was to bring down the Somoza dynasty.

Luis Somoza Debayle would die of a heart attack in 1967, and the reins of government were then handed over to the youngest Somoza, West Point graduate Anastasio Somoza Debayle. Somoza the younger ran Nicaragua like it was his own personal fiefdom, his brutality and corruption shocking the international community, but the US continued to support him until the very last moment.

By 1977 all of Nicaragua was swept up in strikes and insurrectionary violence against the dictator Somoza, and his feared National Guard unleashed a reign of terror across the nation. Pedro Chamorro, a critic of Somoza and the editor of the conservative newspaper, La Prensa, was murdered in 1978, and the Somoza was widely suspected of having ordered the newsman’s death.

Sandinista rebels began to take over major towns and cities, and Somoza’s National Guard responded with the relentless aerial bombardment of civilian centers. Some 50,000 people died during this period, and since war conditions prevented burials in cemeteries, bodies were simply cremated in the streets.

On June 20, 1979, ABC news reporter Bill Stewart and his interpreter, Juan Espinosa, were stopped at a National Guard checkpoint in the capital of Managua. Troops ordered the two out of their car and escorted them a few yards from the vehicle. ABC cameraman Jack Clark remained in the car, filming the entire encounter. The soldier in charge made Stewart lie face down on the ground, moments later shooting him in the back of the head at close range.

The Guardsmen then murdered Espinosa. Miraculously, Clark managed to put the car in reverse and evade the killers. That evening his film was broadcast on television news all around the world. In the US, there was so much public outrage over the killings that President Jimmy Carter was finally forced to cut military aid to Somoza. Less than a month later, on July 19, 1979, the dictator fled the country and the National Guard surrendered to the great-grandsons and granddaughters of Augusto César Sandino.

_____________________________________________

UPDATE: As the decades flew by, the Sandinista government proved itself to be tyrannical. Not as cruel and ruthless as the Somoza regime of the 1970s, but a dictatorship nevertheless. The current president of Nicaragua, Daniel Ortega, is particularly odious. Once a leader of the Sandinista National Liberation Front, he has degenerated into a despot that jails and murders his political opponents.

The Ortega dictatorship charged 11 Christian pastors and ministry leaders with money laundering, and on March 27, 2024, sentenced them from 12 to 15 years each in prison. Each defendant had to pay an $80 million. The people of Nicaragua are 45% percent Catholic and 38% Protestant. Fifty eight members of the US Congress sent a letter to the Nicaraguan ambassador in the US, charging the dictatorship with persecuting the pastors. The letter called their imprisonment a “blatant human rights violation” and demanded “these pastors must be released immediately.”

It is a familiar story… the revolution eats itself. Still, there is the memory of Augusto César Sandino, the General of free men.