Elizabeth Catlett: dead at 96

A few words must be said concerning the passing of Elizabeth Catlett, one of the greatest African-American artists and printmakers in the history of the United States. When I received the news that Ms. Catlett died on April 2, 2012, I felt more than a pang of sadness. I discovered her art when I was a teenager embroiled in the civil rights and antiwar movements in the late 1960s. During those years I became familiar with a number of social realist artists of Catlett’s stature, including Charles White, who was briefly married to Catlett in the early 1940s. I have long credited White “as a major influence in my life as an artist“, and it is fitting that I also credit Ms. Catlett as a personal inspiration as well.

In today’s context it is difficult to describe the impact Catlett’s prints had upon many of us in the late 1960s. She had of course been creating her style of social criticism since 1946, when she moved to Mexico City and began producing amazing lithographs, wood and linoleum cut prints with El Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP – The Popular Graphic Arts Workshop). Activists in the 1960s discovered Catlett’s older works, and since her graphic narratives were as relevant to the 60s as they were in the 1940s, they were given life and meaning by a new generation.

However, Elizabeth Catlett was not one to rest on her laurels; she met the challenges of the late 1960s with uncommon artistic ferocity and political clarity, producing images of unparalleled beauty and compassion. I was 16 in 1969 when I first saw Ms. Catlett’s linoleum cut print Malcolm X Speaks for Us; the work was certainly a reflection of the times, but it also was a lightning rod that led many to discover Catlett’s wider body of work. Her focus was on the African-American experience, though Catlett’s voice was universal. She addressed the hopes, dreams, and problems of her adopted country of Mexico with a good deal of empathy, nonetheless, Ms. Catlett’s works exemplify a clear and profound love for all of humanity.

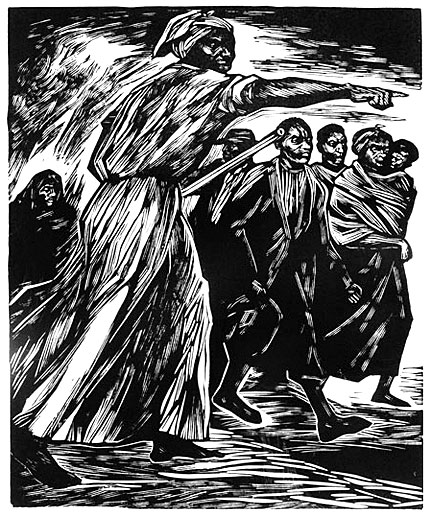

The provocative nature of Catlett’s overtly political works is embodied in her masterful 1975 linoleum cut simply titled Harriet, a tribute to Harriet Tubman, the heroic African-American abolitionist. For eight years Tubman led an “Underground Railroad” network that liberated hundreds of blacks from slavery states in the South, helping them to escape to freedom in the North. The print was a reworking of an earlier linoleum cut by Catlett from 1946 titled, In Harriet Tubman I helped hundreds to freedom, which was part of the artist’s I am the Negro Woman series of prints from that period.

Catlett’s updated 1975 print was aesthetically superior to her original linoleum cut; she applied impressive skills in holding delicate lines in Harriet while giving an elegant appearance of form in Tubman’s dress. Catlett worked amazing textures into the newer print, from coarsely gouged to finer engraved-like lines. But politically, the changes made by Catlett were more important – and volatile – than the artistic ones. She portrayed the leader of the underground railroad as an armed freedom fighter carrying a rifle, a brazen act given the political atmosphere in the early 1970s.

Historic illustrations from the late 1800s usually pictured Harriet Tubman with a rifle, and though it is hard to be certain, that long gun was most likely an 1803 Harpers Ferry rifle chambered in .54 caliber. Tubman is also known to have been armed with a large revolver, in all probability the six-shot .36 caliber 1851 Colt Navy Revolver. When Tubman ran her underground network, Blacks were forbidden by law from owning or carrying firearms, it was even illegal for Whites to furnish guns or knives to Blacks that had been freed from slavery.

Elizabeth Catlett portrayed Harriet Tubman as a great hero and defender of human liberty, an indisputably accurate depiction. Tubman in fact became known as “Moses” to her people for having rescued hundreds of slaves from inhuman bondage. Even so, Tubman’s daring and courageous acts could not have been possible without the use of firearms; with rifle and pistol she defended her people against the unspeakable cruelty of slave masters, bounty hunters, and all others who profited from human bondage. Tubman worked with the Union Army to defeat the Confederacy during the U.S. Civil War, and actually became the first woman in U.S. military history to prepare and help command an armed military assault, the Raid at Combahee Ferry in South Carolina; the military operation freed more than 750 slaves.

By emphasizing Tubman carrying a rifle in the cause of freedom, Catlett was directly addressing millions of African-Americans over the question of armed self-defense vs. non-violent action. Of course, most of Catlett’s art was not as confrontational as Harriet, the largest part of her oeuvre was given to tender and compassionate observation of humanity. Catlett’s works spoke of, not just oppression and injustice, but the capacity of people to create a better world. When searching for an artist with a deep-rooted commitment to social justice and equality, one need not look any further than the immortal Elizabeth Catlett.