How the Modern West was Won?

As an aficionado of modernist aesthetics and goals, my heart took flight when I read that the Los Angeles County Museum of Art was offering an important new exhibit on modernism, The Modern West. LACMA claims The Modern West offers “a fresh and innovative look at modernism through a very personal lens,” however, in the museum’s publicity, the use of a hackneyed phrase indicates something else. Regrettably LACMA chose to promote its exhibition with the following unfortunate words – “Discover how the modern west was won in the first exhibition to hightlight how our local landscape shaped the modern art movement.”

Myths die hard, like the American mythos of heroic pioneers fighting off “blood-thirsty savages” in order to “win the west.” The west was “won” through a brutal campaign waged against indigenous people, a fact that seems to have evaded LACMA. Of those painters in The Modern West exhibit, LACMA’s promotional material highlights Frederic Remington, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Jackson Pollock.

The alcoholic, hard-drinking, swaggering Pollock, is been made into an iconic champion of modern American art, but in the context of LACMA’s winning the west jargon, he also represents the unstated opinion that “divine providence” led to the rise of America. I’m reminded of the 2005 PBS special, Imagining America: Icons of 20th-Century American Art, where artist Lee Krasner referred to Pollock, not only as a “pioneer,” but as someone imbued with the spirit of “manifest destiny.”

If LACMA’s The Modern West offers “a fresh and innovative look at modernism,” it’s going to have to be an exceedingly powerful show before I forget that the museum screened, They Died with Their Boots On, a fictitious and wholly inaccurate depiction of General George Armstrong Custer. Starring Errol Flynn as Custer, the movie was presented as part of LACMA’s 2006 retrospective film series honoring legendary star Olivia de Havilland. The 1942 film would be the last time Flynn and de Havilland appeared together, and apologists insist the motion picture is nothing more than a rousing action adventure, but Hollywood never produced a more perfect example of institutionalized racism against Native Americans.

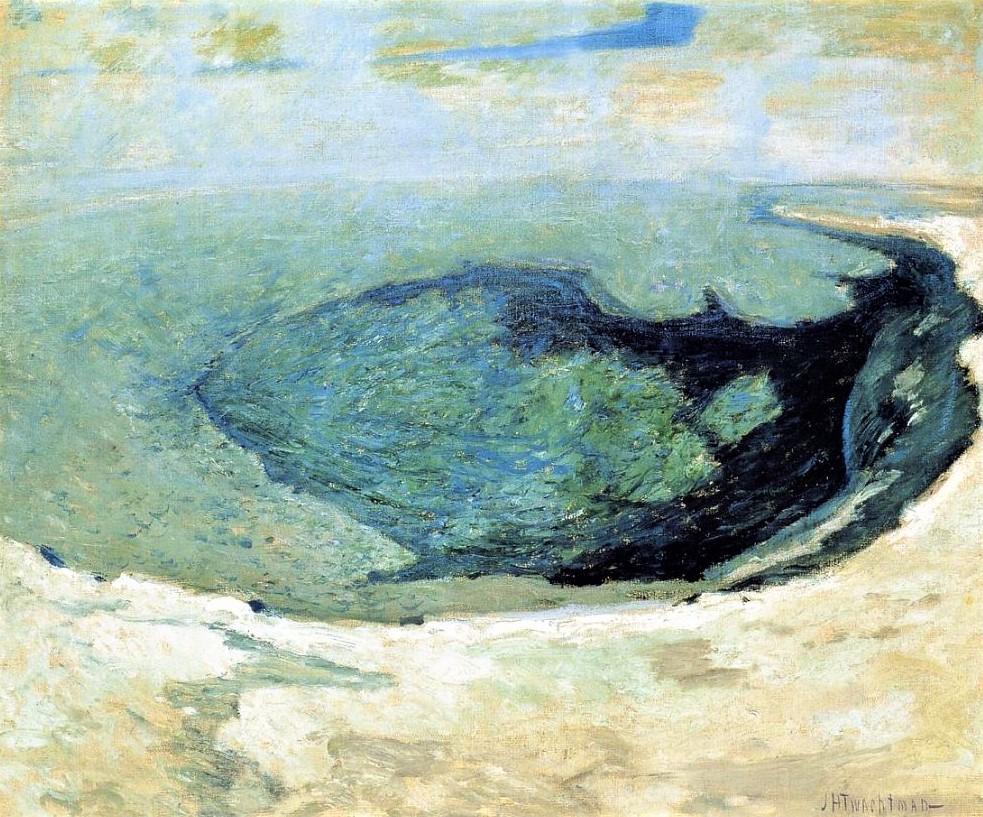

Concurrent to the exhibition of approximately 100 paintings, watercolors, and photographs by the various artists in The Modern West, LACMA will also be holding a number of special events pertaining to the subject. Of special interest is the April 15th lecture by Bill Anthes of Pitzer College, Native Modern: American Indian Painting. Anthes, Assistant Professor of Art History at Pitzer College and author of the book, Native Moderns, argues for the inclusion of indigenous artists into the canon of American modernism.

I’ve made the same argument on numerous occasions, as with my short web log post from 2004, Aztec Art: Roots of Modernism. But LACMA seemed to include Anthes’ lecture as an afterthought, as if feeling guilty for the clumsy PR. It’s a shame that LACMA’s “fresh and innovative look at modernism” does not include a deeper examination of Native American modernist visions.

Despite my apprehensions, I nevertheless intend to see LACMA’s The Modern West, as it’s an important step in reevaluating the history of modernism. In relocating modernism’s traditional center from Europe and New York to the great American West – the door is being opened to other, long silenced voices.