Why Beauty Matters

In November of 2009 the BBC network in the UK ran The Modern Beauty Season, a series of films produced for television on the concept of beauty in modern art. The series offered six films that ran the gambit of opinion on contemporary art, but it is the film by the conservative British philosopher Roger Scruton, Why Beauty Matters, that I wish to address here.

As a working artist I found myself in general agreement with some points made in Scruton’s film; that appreciating and creating things of beauty is a necessary part of the human experience, that beauty is “a value as important as truth and goodness,” that it has been central to civilization, and that “it is not just a subjective thing, but a universal need of human beings.”

We agree that there is a spiritual aspect to beauty – though we would likely disagree over a definition of “spiritual.” So yes, beauty does indeed matter, and I am of the opinion that it should be central in all the various disciplines of the arts; but perhaps my definition of such an elusive and ephemeral thing as beauty is more expansive than Mr. Scruton’s, whose vision seems to be restricted to what is known as European “classicism.”

I am at variance with a number of his assumptions and inferences; the particulars of my differences are in part laid out in this article.

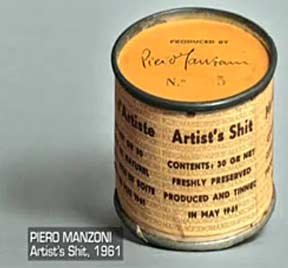

Postmodern art makes for an easy target, as it is has altogether forsaken skill, craft, and beauty – the very things most people think of when considering the arts. Postmodern artists from the late 1960s to the early 1970s attempted to remove art from the marketplace by creating “conceptual” works, i.e., performance, video, installation, etc., instead of merchandise for market consumption. We have seen how well that worked out.

The art movement that previously strove for the “dematerialization of the art object,” as pro-conceptualist art critic and activist Lucy Lippard put it in 1973, has today placed itself in unwavering service to the elite art establishment it once sought to circumvent.

Capitalism co-opted and absorbed conceptual art, which has become more of a commodity fetish than any of its other art world predecessors; it is synonymous with astronomical prices, billionaire art collectors, and shamelessly venal celebrity art stars – all good enough reasons to disparage it in my view. But that is my critique, not Roger Scruton’s.

In Why Beauty Matters the soft-spoken and erudite Scruton makes a populist argument against much of contemporary art that will no doubt strike a chord with significant numbers of people.

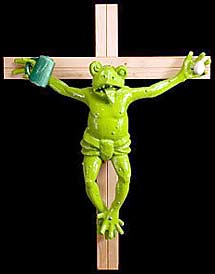

But seeing as how the general public is largely indifferent to the goings-on of the art world, Scruton’s presentation provides surprisingly little insight into the field of art, instead he sets up a straw man, fueling the fires of misunderstanding by focusing on the more egregious examples of postmodern excess—for instance, Turner Prize winner Martin Creed’s Sick Film Work 610, then suggesting that liberal elites, moral dissipation, and the loss of religion are the reasons behind such works being produced.

What I find interesting is that Scruton does not explicitly state such opinion in his film, he alludes to it, but he reveals his stance with more clarity and honesty in his writings. For example, in a 2006 essay titled Quo vadis? (Latin for, “Where are you going?”) he unambiguously declared his position:

“We cannot rescue our civilization merely by overthrowing the Marxist, post-Marxist, deconstructionist and postmodern ideologies that inhabit the universities. Even if we returned to the classical curriculum, and taught European culture as it was taught to me, that would not bring back the public consensus on which our civilization depends (….)

The most important thing on which European people can be encouraged to agree is that our inheritance is Judaeo-Christian, and that the Bible, and the two religions built on it, are an indispensable part of our culture.”

There are moments in Why Beauty Matters where Scruton sounds like a critic of the capitalist culture industry, as in the following comment;

“Our consumer society puts usefulness first, and beauty is no better than a side-effect. Since art is useless it doesn’t matter what you read, what you look at, what you listen to. We are besieged by messages on every side, titillated, tempted by appetite never addressed, and that is one reason why beauty is disappearing from our world.

‘Getting and spending’ wrote Wordsworth ‘we lay waste our powers.’ In our culture today the advert is more important than the work of art, and artworks often try to capture our attention as adverts do, by being brash or outrageous (….) Like adverts, today’s works of art aim to create a brand, even if they have no product to sell except themselves.”

On the surface level Scruton’s remarks have a ring of truth to them, but ultimately he never attributes the crisis in modern art to the pernicious role of money, as did Robert Hughes in his fabulous The Mona Lisa Curse. Instead Scruton simply blames liberalism and the waning influence of religion in the West.

While Scruton points out how certain philosophers of old influenced the world of European art, and he briefly makes mention of the substantial impact science had upon the arts, he never once mentions the central issue of patronage, a deciding factor in art history.

In the film Scruton takes an almost mystical approach in describing how spirituality and religion have historically been linked to concepts of beauty, while completely ignoring the role of the Church as the primary financial backer and authority in the arts. Likewise, he ignores the role of monarchists and other ruling elites, who also tightly controlled art by way of patronage. Artists did not begin to free themselves of this rigid control until the early 19th century.

In one of his recently published articles, Beauty and Desecration, Scruton wrote that “Modern artists like Otto Dix too often wallow in the base and the loveless.” That observation reveals much about Scruton, and how the two of us have divergent concepts of what is beautiful. Dix lived through one of the most tumultuous periods of German history. He fought in the trenches of World War I where he saw humanity ripped to shreds in the world’s first mechanized war.

At war’s end he became politicized, and through his art expressed disdain for militarism and Germany’s ruling class. He witnessed the fall of the German monarchy, the rise of the Weimar Republic, and the Nazi seizure of power. In their brutal repression of the arts, the Nazis removed Dix from the Prussian Academy and his professorship at the Dresden Art Academy, his dismissal letter declaring that his art “threatened to sap the will of the German people to defend themselves.”

Dix was forbidden to exhibit by the Nazis, they removed his artworks from museums and had them destroyed. They included his paintings in their infamous 1937 Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibit, meant to condemn modern art as the work of Bolsheviks, “Jews,” and the insane. Dix was forcibly conscripted into the fascist home guard in 1945 at the age of 53, captured and later released by the French army at the close of the war. Given that chronicle, it is shocking that Scruton would accuse Dix of wallowing in the “loveless.”

What type of art would Scruton have preferred to see Dix paint during that despairing period… inoffensive still lifes? Considering the barbarity that was all around him, it is remarkable that Dix painted anything at all, but even the most distorted of his expressionist grotesqueries contained more truth, and yes, beauty… than all the realistic classical nudes and respectable portraits commissioned by the German bourgeoisie of the period. Dix’s creations were beautiful simply by virtue of the truths they told.

In Why Beauty Matters Scruton disavows modern architecture, and at one point in the film he takes the viewer on a tour through the community near London where he grew up, “a charming Victorian town with terraced streets and Gothic churches, crowned by elegant public buildings and smart hotels.”

Scruton’s community was forever altered starting in the 1960s, when homes were demolished to make way for a substantial number of large office buildings and a bus station that brought people to and from London. Scruton claims the brand new modernist style buildings were “all designed without consideration for beauty,” and were proof that “if you consider only utility, the things you build will soon be useless.”

Today the office buildings and the bus station are boarded up and abandoned; everything has been vandalized and covered with graffiti. The once thriving community is now dilapidated and in a state of neglect, “but we shouldn’t blame the vandals” Scruton insists, “this place was built by vandals, and those that added the graffiti merely finished the job.”

Standing in front of a large deserted office, Scruton says; “This building is boarded up because nobody has a use for it, nobody has a use for it because nobody wants to be in it, nobody wants to be in it because the thing is so damn ugly.”

Of course people have a use for the building! There are countless ugly buildings currently serving as vital centers of community life, whether in housing, commerce or government.

While uninviting architecture is depressing, that is not what leads to the collapse of urban centers; cities and towns thrive or shut down for economic reasons. The property owners that financed and directed the construction of the buildings Scruton deems offensive, have now found it more profitable to close and padlock their properties, or have them razed to the ground.

In his analysis of architecture and urban decay Scruton makes no mention of government policy or economics, as if towns and cities collapse into ruin simply because people have an aversion to unsightly architecture. He says nothing of the pressures brought about by layoffs and astronomical unemployment, cuts in government services, inflation, recession, and an increasingly globalized economy.

He does not talk about the role of banks, real estate firms, and other financial interests, the destruction of British industry, and crushing unemployment that by 1982 had put well over 3 million people out of work.

In Why Beauty Matters Scruton seems reluctant to say just who is responsible for all of this unappealing architecture, but as I have previously noted, he is more than willing to lay blame in his published articles. In The modern cult of ugliness, a December 2009 article for the Daily Mail, Scruton lets us know who the culprits are; “official uglification of our world is the work of the ivory-towered elites of the liberal classes, people who have little sympathy for how the rest of us live and who, with their mania for modernizing, are happy to rip up beliefs that have stood the test of time for millennia.”

Roger Scruton’s credentials are impeccable; a Senior Research Fellow in Philosophy at Oxford University’s Blackfriars Hall, a Research Professor at the Institute for the Psychological Sciences in Arlington, Virginia, a Fellow of the British Academy, and the author of more than 30 books on cultural and political affairs. As should be apparent from reading this article, this learned man is also an ardent conservative. Scruton is quite well known in Britain for his outspokenness, but less renowned in the US, apart from being appreciated in conservative circles. He is a Resident Scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, home to such US neocon luminaries as Michael Novak and Irving Kristol, the now deceased “godfather of neoconservatism.”

Mr. Scruton has been a columnist for a number of conservative publications. In Totalitarian Sentimentality, his Dec. 2009 article for the conservative journal The American Spectator, Scruton makes clear his view that conservatism best guards all things noble and just, while liberalism is but a hair’s breadth from tyranny and despotism. Scruton’s fervent political conservatism is inseparable from his views on art and culture.

I have posted Roger Scruton’s Why Beauty Matters directly below, and I encourage everyone to view the film in its totality. For more on Roger Scruton please read Roger Scruton at TRAC 2014, and my follow-up report, TRAC 2014: Part II.