Defend the Detroit Institute of Arts

Why is an artist in Los Angeles, California writing to defend a museum in Detroit, Michigan? Because I understand that whatever the fate of the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA), it will affect museums all across the United States. The agony of Detroit is one of today’s enormously complex political and economic questions, but one that American artists must grapple with. While many in the U.S. arts community support the DIA in its time of crisis, there are those that side with the forces bent on selling off the museum’s collection of masterpieces. One such voice is James Yood.

Mr. Yood teaches modern and contemporary art history at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. In addition, Yood is a regional correspondent and art critic for ArtForum, and a contributing editor to art ltd., where he published an editorial that was circulated in the Visual Art Source (VAS) newsletter on Aug. 9, 2013. I felt compelled to respond to Mr. Yood’s editorial, which calls for the “deaccessioning” or selling of art treasures in the permanent collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA), in order to pay off Detroit’s multi-billion dollar debt. On May 26, 2013, I wrote a web post titled Killing the Detroit Institute of Arts, that addressed that same issue.

Mr. Yood’s editorial titled, Deaccession in the Civic Context, can be read on the VAS website. Excerpts of Yood’s editorial will be contested by this author in the following:

James Yood: “I’m not sure why everyone has their knickers in a twist over the possibility that the Detroit Institute of Arts might auction off some of its collection to assist Detroit defray an $18 billion deficit, one that has put the city into bankruptcy.”

It is difficult to take Yood seriously when in his opening sentence he uses the idiom – “knickers in a twist” – to belittle those who are outraged over the anticipated pillaging of the Detroit Institute of Arts. The expression of ridicule is usually aimed at someone who is upset about a trivial issue. The matter at hand, the value and future of American museums and the public’s access to them, is far from being a frivolous affair.

On March 14, 2013, Michigan’s Republican Governor Rick Snyder appointed Mr. Kevyn Orr as the unelected “Emergency Manager” of the city of Detroit.

On July 18, 2013, Detroit filed for Chapter 9 bankruptcy; it is the biggest municipal bankruptcy filling in U.S. history. With near dictatorial powers to restructure the city’s finances, make cuts to government spending, and see to it that the city’s debts are paid, Orr set about ascertaining the value of everything the city might be able to sell, from the Detroit Water and Sewage Department to the Coleman Young International Airport. The collection of the DIA was quickly targeted by Orr as a potential “asset” to be sold.

For his part Detroit’s Mayor Dave Bing, a Democrat, cut $247 million from the city’s budget last year, and has submitted a 2013-14 budget that will bring even more extreme cuts to social services and government spending. Emergency Manager Orr proposes huge cuts to the pensions and health care programs of police and fire departments, as well as emergency medical teams and other public workers, not to mention slashing the pensions of retirees.

The massive privatization of public assets and services is well underway – and it is a bi-partisan attack. Rather than have his editorial raise volatile political issues, Yood instead launches a dissertation on the history of “deaccession” and how the practice of de-acquisitioning a collection supposedly benefits art museums:

James Yood: “Deaccessioning art has been standard practice for so long as to be an integral part of the museological landscape (….) That’s the way it works – it might be the museum world’s dirty little secret, but trust me, all museums deaccession, it’s happening where you live, in the museum you love, amidst the permanent collection you always thought was, well, permanent. It’s how museums prune their collections, dispose of duplicate material, etc. (….) When the Art Institute of Chicago or a similar institution sells a Picasso from its permanent collection at Christie’s or the like it is obligated to use all of the funds it accrues – and these can run into millions of dollars – solely in its acquisitions budget.

In other words, institutions that are members of the American Alliance of Museums (AAM) have agreed never to sell works from their permanent collections to pay salaries or operating budgets, but are free to deaccession to amass funds to buy that Malevich or LeWitt they’ve always coveted.

(….) If a museum has 30 paintings by Monet (the Art Institute of Chicago currently owns 33), why not provide another museum or collector the opportunity to purchase the one your curators believe is the least significant, and in so doing get the funds to buy that Tissot or Morisot that will make your collection broader, richer?”

It is hard to believe that Mr. Yood could miss such an obvious point. The Detroit Institute of Arts is not being asked to voluntarily auction its art treasures “to assist” the government of Detroit in paying down the city’s long-term debts. Nor is the museum planning to “prune their collection” as Yood put it, in order to acquire new works. The DIA’s collection is estimated to be worth around $2 billion. Simply put, the government of Detroit has declared that the museum’s entire collection is a “city asset” that the state can sell at auction, an assertion that the director of the DIA, Graham W. Beal, strongly refutes.

Mr. Beal insists that the DIA’s holdings are a public trust. Apparently Michigan’s top law enforcement official, Attorney General Bill Schuette, agrees with him. On June 13, 2013, Schuette’s office released a 22-page opinion that read in part: “The art collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts is held by the City of Detroit in charitable trust for the people of Michigan, and no piece in the collection may thus be sold, conveyed, or transferred to satisfy city debts or obligations.”

Mr. Yood mentions the principles of the American Alliance of Museums in an attempt to further his position that deaccession can fund new acquisitions for a museum, but again, the profits from a forced sale of DIA holdings will not go to the museum, but to Detroit’s creditors. Yood does not tell his readers that the president of the American Alliance of Museums, Ford Bell, opposes a forced sale of the DIA’s holdings, saying that “the museum should be a rallying point for the rebirth of Detroit and not a source of funds.”

James Yood: ” Back to Detroit, though – because the fig-leaf of selling permanent collection art to raise funds for acquisitions isn’t at play here – my conclusion is that since that city is in bankruptcy, in fiscal extremis, and as citizens and businesses and tourists are all going to be asked to help, to make sacrifices, why shouldn’t its art museum?”

Mr. Yood’s way of thinking should sound familiar. What comes to mind is how the Bush and Obama administrations handled the economic crisis after the pirates of casino capitalism crashed Wall Street on September 29, 2008. The reckless speculators responsible for the crash were rewarded with government bail-outs totaling hundreds of billions of dollars… all provided by U.S. taxpayers. In 2010 PBS reported that the actual cost of bailing-out Wall Street was close to $12.5 trillion. In the wake of the 2008 crash, millions of Americans lost their jobs and their homes, but the Obama administration did not arrange a bailout for them.

Now that Detroit has crashed, developers, speculators, investors, and assorted oligarchs have descended upon the city like a murder of crows. The asset stripping Emergency Manager Orr is holding a fire sale, and the money bags are itching to buy.

Oh, the working people of Detroit will have to “make sacrifices” to be sure; they will suffer the loss of their hard earned pensions, health care plans, government services, and perhaps their homes and livelihoods. They may also lose the DIA. But the plutocrats will get along fine, in fact, just as with the Wall Street Crash of 2008, they will make out like bandits.

In March of this year CBS Detroit reported that Forbes Magazine published its annual list of the richest people in the world, and in the words of the CBS local affiliate, the list revealed that “10 percent of the billionaires’ club resides right here in and around the Motor City.” The station also reported that the combined wealth of these 12 individuals tops $5.4 trillion. Let us take a look at just two of these Detroit billionaires, Mike Ilitch and Dan Gilbert, and how they will “make sacrifices” for their city.

Mike Ilitch owns the Little Caesar’s Pizza chain, as well as the Major League Baseball team the Detroit Tigers, and the Detroit Red Wings National Hockey League team. Forbes rated Mr. Ilitch’s net worth at $2.7 billion as of March 2013. Ilitch has convinced Mr. Orr and the Detroit city government to spend over $400 million on building a new hockey arena for Ilitch’s Detroit Red Wings. As Emergency Manager Orr slashes the retirement pensions and health care plans that many thousands of people depend on, as he cuts the pay of police, firemen, and emergency medical teams that serve the city, as street lights are permanently shut off, he will also be funding Mr. Ilitch’s new sports arena with monies provided by Detroit tax payers.

Dan Gilbert tops the Forbes list of Motor City Moguls. With an estimated worth of $3.5 billion, Gilbert owns Quicken Loans, the NBA’s Cleveland Cavaliers, and the Detroit based real estate company, Rock Ventures. CNBC reported that Gilbert wants to “tear down chunks of Detroit,” quoting the mortgage tycoon as having said, “There’s something like 128,000 buildings, commercial and residential, that need to be removed. And once that happens, there’s going to be opportunity…where developers and people can start making investments again.” Guess who will be there to make a killing. According to Yahoo News, Gilbert is “buying up, remodeling, and repurposing downtown properties” like they were going out of business, because… well, they are. Big fish eats little fish, or as John D. Rockefeller infamously put it, “The way to make money is to buy when blood is running in the streets.”

So according to James Yood, the Detroit Institute of Arts will just have to make sacrifices like everybody else. And when it is all over, when the schools, libraries, and hospitals are shuttered, and those 128,000 buildings that Mr. Gilbert dreams of bulldozing are turned to dust like the rest of Detroit’s history, the pirates of casino capitalism will have won another victory. But since the DIA will have been forced to sell their collection, the oligarchs may very well walk away from their latest triumph with a few of the DIA’s “assets” tucked into their investment portfolios.

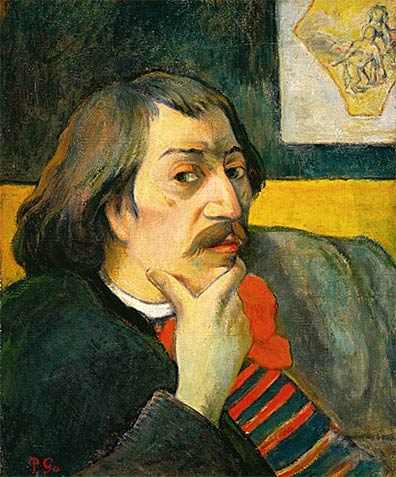

James Yood: “Does anyone really believe that the DIA would no longer be a great art museum if they carefully deaccessioned about five or six works – choose among their great Poussin, Van Eyck, Caravaggio, Brueghel, Bellini, Cezanne, Bronzino, Van Gogh, or many others – and raised and then chipped in about $1 billion of the $18 billion Detroit owes? What’s wrong with a museum functioning as a good citizen in a time of crisis?”

Does anyone really believe that what we are witnessing in Detroit is anything less than a massive redistribution of wealth from those on the bottom to those on top? The great Poussin, Van Eyck, and Caravaggio canvases Yood mentions might very well end up in some billionaire’s private collection – never again to be seen by the public. There is a great certainty that the artworks would be moved out of Detroit, or perhaps out of the U.S. entirely.

What Yood proposes – that the DIA sell its masterpieces to help pay down government debt – flies in the face of the autonomy from government decree and control enjoyed by U.S. museums. What about the endowments made to the DIA over the years, works and collections bequeathed to the institution with the understanding that the donated artworks became part of a public trust? Are these works merely to be stripped away as “assets,” ignoring the original intentions of their donors? Diego Rivera’s glorious Detroit Industry mural series at the Detroit Institute of Arts was commissioned in 1932 by the museum’s Director, William Valentiner. Like all of Rivera’s monumental fresco paintings, he intended Detroit Industry to be a public work of art, specifically, a tribute to the American working class. Is this historic work now to be privatized? I should mention that the DIA commissioned Rivera during the Great Depression, and throughout that period of extreme crisis, there were no demands that the museum sell-off its collection.

The government of Detroit is pressing for a forced sale of the DIA’s art treasures, and not just of “five or six works” as Yood would have you believe. On August 5, 2013, Detroit’s Emergency Manager Kevyn Orr revealed that Christie’s auction house had been contracted by the city to appraise the holdings of the DIA, and that the city would pay Christie’s $200,000 for the appraisal.

This is a serious indication that the city fully intends to liquidate the DIA’s collection, otherwise, why would it pay such an outrageous appraisal fee while city workers are having their pay, hours, health care benefits and pensions cut to the bone? Christie’s is expected to complete their appraisal of the DIA collection by October, 2013.

Detroit is not the only major U.S. city faced with bankruptcy, it is just the first to declare it. The big picture is that the U.S. government currently faces debt that is expected to be somewhere around $20.541 trillion dollars by the end of 2013.

Given his editorial stance Mr. Yood should have absolutely no objection to the collections of America’s top museums being sold off to help bring down the national debt. The National Gallery of Art (NGA) in Washington, DC has a stunning collection surely worth a few billion dollars on the auction block. The NGA has in its permanent collection the only painting by Leonardo da Vinci in the America’s – the incomparable portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci (just think of the millions that painting alone would fetch at Christie’s or Sotheby’s).

But why stop with the National Gallery of Art? Let government force the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, DC, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, in Boston, Massachusetts, the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, California, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, and every other great American art museum large and small, to sell their masterpieces in order to help bring down the U.S. debt. The logic of Yood’s position demands, “never mind that these museums have played absolutely no role in creating the government’s enormous debt, make them pay regardless.”

James Yood: “Those paintings, all of which somehow left collections in Europe to come to Detroit in the first place, would just move on to another life somewhere else. Are museums frozen tight, never to evolve, mausoleums for art, or might a little interior ebb and flow actually be interesting, and freshen the eye?”

Let us apply Yood’s logic to the trillions of dollars worth of federal debt faced by the U.S. government. There are scores of famous monuments in the U.S. that could be placed on the auction block in order to help pay down the national debt, take the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor for instance. Heck, it was a gift from France that moved “on to another life” in Manhattan. Similarly, the original U.S. Constitution on display in the Rotunda of the National Archives Building in downtown Washington, D.C. would make a fine edition to some oligarch’s private collection.

James Yood: “I hear no one suggesting that the DIA’s entire collection should be sent tomorrow to Sotheby’s for immediate dispersal (though such an act could theoretically bring in more than $18 billion – what’s the opening bid for their Diego Rivera murals?).”

Mr. Yood should read the comments section of mainstream websites that are publishing reports on the possible auctioning of art treasures held by the DIA. There is unfortunately a great number of people who think it is a grand idea, and Yood’s editorial does nothing to disabuse them of the notion. Though he cannot name anyone that might suggest the entire DIA collection be put on the auction block, Yood ignores the preparatory moves currently being undertaken to do just that. He barely conceals his excitement over the prospect of the entire DIA collection bringing in over $18 billion on the auction block, and shamelessly jokes about the bidding price for Rivera’s Detroit Industry mural series at the DIA.

That an art critic for ArtForum writes such bilge in support of a forced sale of a major museum’s permanent collection is beyond disgraceful.

I would like to reiterate my view that plans to seize and auction off the collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts, if successful, will be a strategy visited upon museums all across the country. We should all give direct assistance to the DIA, by visiting the museum’s website to make a donation or by signing up to become a member.

James Yood: “But if your community is dying you have to consider what you can do to help it survive. If the Art Institute of Chicago or your local art museum can (and did, and will again) sell something like a first-rate Braque, why can’t the Detroit Institute of Arts sell a first-rate Brueghel? Why?”

Yood writes about bankruptcy as if it were an act of God for which we mortals must pay penance, and he makes no attempt at describing the context of the crisis… the political and economic decline of the U.S. over the years and how this has deeply impacted Detroit (not to mention other U.S. cities). He writes as if the state auctioning off the permanent collection of a major American art museum is not an earth-shattering political event with profound national and international implications. He fails to explain why the DIA should be made to pay for the greed and mismanagement of those who are actually responsible for Detroit’s financial crisis. In essence, he writes as an apolitical intellectual.

Yood’s position denies the museum as a commons, a vital gathering place where people can share ideas and collective experiences. In the case of the Detroit Institute of Arts, a museum founded in 1885, we are talking about a very rich history indeed. The DIA is an integral part of the community, city, and nation, not a building full of what creditors and bureaucrats might simply see as “assets.”

To say that “art is for everyone” might sound like a glib cliché to some, but for the people of Michigan’s Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties outside of Detroit, the phrase was taken seriously. During an August 7, 2012 election, voters passed a tax increase for their Tri-County area that would help fund the DIA. The magnanimous vote indicates just how important the DIA is to the people of Michigan.

Currently Oakland County supplies approximately $9 million a year to the DIA, Macomb County puts in around $7 million, and Wayne County pays some $10 million. These monies are a significant portion of the DIA’s current operating budget, which has been cut drastically over the years. Personally, I was ambivalent about the tax increase, thinking that it would not shield the museum from escalating cuts, but the good people of the Tri-county had their say. However, there is a caveat to the recently passed legislation. Oakland County wants to pass a resolution that stipulates, if the state seizes and sells any art from the DIA collection in order to satisfy creditors, the special Tri-County tax will be terminated. Macomb and Wayne counties plan to follow suit.

To counter Yood’s hyperbole head on, if a community is dying, the first obligation of the citizenry would be to ascertain who is responsibility for killing it – and then hold that individual or group accountable. The working people of Detroit are not responsible for the city’s financial mismanagement and collapse, and neither is the Detroit Institute of Arts.

The venerable Merriam-Webster dictionary defines the word “museum” as follows: “An institution devoted to the procurement, care, study, and display of objects of lasting interest or value; also: a place where objects are exhibited.” Webster’s also defines the word “stock exchange as follows. “1): a place where security trading is conducted on an organized system. 2): an association of people organized to provide an auction market among themselves for the purchase and sale of securities.”

Perhaps the problem with James Yood’s editorial is that he has forgotten the difference between a museum and a stock exchange.

— // —

UPDATE: On August 18, 2013, the Detroit Free Press published an article titled, “Christie’s appraisal will reveal value of Detroit Institute of Arts’ collection.” I encourage readers of this web log to read the article. Here is a brief excerpt:

“‘This is like the weighing of souls,’ said Maxwell Anderson, director of the Dallas Museum of Art. ‘This is biblical stuff, not the approximations that insurance companies look for. It’s extremely problematic for all museums, because it alters the public’s perception of artworks from being ciphers of public heritage of transcendent value, to objects for sale to pay other people’s debts.'”