Sanford Biggers Is Not An Oracle

On May 11, 2021 the Smithsonian Magazine ran an article with the headline, This Monumental ‘Oracle’ Statue in NYC Subverts Traditional Sculpture. Artist Sanford Biggers was being touted by the magazine as the first artist to be invited by the Rockefeller Center to take over their campus with a multimedia survey exhibition. He was also being applauded for exhibiting his 25-foot tall Oracle bronze statue at the Fifth Avenue entrance to the Channel Gardens at Rockefeller Center. The statue is considered the centerpiece of the Biggers take over.

Whatever profundity the Oracle bronze supposedly possesses is outweighed by its absurdity; it is hard to take seriously.

The enormous African head teetering on top of a Lilliputian Greco-Roman figure holding a golden torch, does not provoke deep thought, but laughter. It reminds one of the jackalope, that faux American critter created by a 1930s taxidermist who grafted antlers onto the head of a jackrabbit carcass.

Oracle is part of Biggers’ Chimera project, it is the largest statue in that series. His Chimera sculptures, some of which are exhibited at the Rockefeller Center, combine African masks with classical European depictions of the body.

In the case of Oracle, humongous size is not matched by a beauty of equal magnitude.

Aside from its droll unsightliness, there is a three-ring circus side-show angle to Oracle. Biggers outfitted the statue with an interactive component allowing the public to ask the sculpture questions, once they activate a QR code. According to the artist, Oracle answers with the voices of “various celebrities” (well of course—there must be celebrities), and the responses will be “mysterious, poetic vagaries which will hopefully be, if not helpful, at least mystifying.” Perhaps Oracle could soothsay how far away in the future it will be before Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa speaks with a QR code initiated celebrity voice.

On a wide, double stepped, white platform, the Oracle sits on its royal black throne. Emblazoned on the seat of power one finds a repeated circular image of what appears to be a lotus blossom. A closer look reveals each petal of the lotus is the cross-section of a slave ship filled with its human cargo. It is an accursed flower, and it is Biggers’ vision of America.

The exhibition includes sculptures, mixed media “paintings” made on antique quilts, video, audio, a “mural” (if you choose to call a Photoshop file printed by an inkjet printer a mural), and flags, because, what would an art exhibition be without flags?

Rockefeller Center combines two building complexes, the original fourteen office buildings that were built in the 1930s in the Art Deco style, and four towers built in the 1960s and 70s in the International architecture style. American architect Raymond Hood was the chief architect. Biggers compared himself to Hood, saying “When Raymond Hood was designing this complex, he was grabbing from stories from antiquity, mythology, art, to wind up with this beautiful Art Deco monument. I wanted to reference various cultures and histories as well.”

The prodigious Raymond Hood was not “grabbing” bits from the past to “wind up” with an assemblage—that is the methodology of postmoderns like Biggers. Hood studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s School of Architecture, and in 1911 he graduated from the École des Beaux-Arts, Paris. His designs were meticulous, purposeful, and pragmatic, bearing Neo-Gothic or Art Deco embellishments. The mythology and art he was supposedly grabbing were the ancient Greek building blocks that Western civilization rests upon; foundations forsaken by postmodernists. Oracle is presumably the dubious stand-in for the “various cultures and histories” that Biggers mentioned.

As with all of Biggers’ works at the Rockefeller Center, the Chimera sculptures are consumed by identity politics—an Afrocentric vision to be precise. So it is odd that he named his sculpture series after the Chimera of ancient Greece, a mythic fire-breathing female creature that was a hybrid of lion, goat, and snake. All of his exhibited works have the intent of dethroning “whiteness” in Western art. They are an attempt to supplant European mythos with blackness. In the language of artspeak, the artist “explores historical depictions of the body and their subsequent myths, narratives, perceptions, and power.” That is a tad more palatable than just saying “he kicks Western civilization in the teeth.”

According to Biggers the Oracle head is based on masks from various African cultures, including those created by the Luba people of the Congo, and the Maasai tribal group inhabiting parts of Kenya and Tanzania. I am left wondering, how does the king-like Oracle come to represent all of Africa? In modern Africa there are fifty-four countries—only one of them, Eswatini (Swaziland), is an absolute monarchy. The two others, Lesotho and Morocco, are constitutional monarchies. It seems Biggers is partial to the supreme power of an African king over the democratic rule of the people. In his view Oracle completes “the rest of the story” told by the classical European statues of Rockefeller Center. He says that Oracle contains “a lot of African elements.” Yet, when studying real world African art, those “African elements” appear to be dreamed up.

Biggers noted the body of Oracle was inspired by the Statue of Zeus that once sat in the Temple of Zeus in ancient Olympia, Greece. Difficult to imagine, since no accurate copies of the statue survive; the temple and its statue were destroyed long ago by earthquakes and fires. In 457 BC the sculptor Phidias created the 40-foot high chryselephantine sculpture of Zeus, King of the Olympian Gods. In this type of sculpture, gold (chrysos) depicted garments and accoutrements, while ivory (elephantinos) represented flesh. It is said Zeus was depicted with his outstretched right hand holding a statue of Nike, goddess of victory. His left hand held a scepter where an eagle perched. The statue became one of the Seven Wonders of the World. That will not be the destiny of Oracle.

Historically the Smithsonian and other art institutions have had few problems discerning persons from gods in artifacts from the ancient world. However the Smithsonian Magazine described Oracle as a “person or deity with an enormous head who sits majestically on a throne.” The statement seems confused because there is no tangible history behind Oracle, no celebrated personages, no gods, no legendary event, just a wan metaphor for black superiority. It is a mash-up where a simulacrum of ancient Greece is pitted against Biggers’ imagined “African elements,” and the winner is Wakanda, the fictional sub-Saharan country made-up by Marvel Comics.

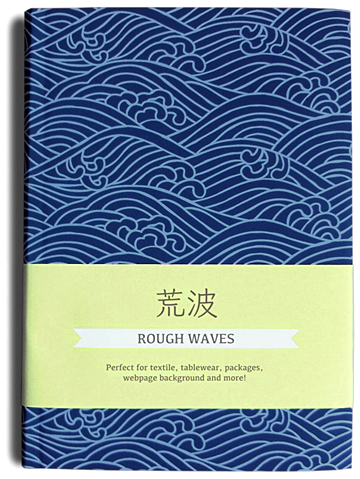

Let us examine the flag series titled Seigaiha that Biggers said he created for the Rockefeller Center flagpoles. Media accounts report the blue flags display “a unique wave illustration designed by Biggers.” The artist says the flags with their wave patterns in white, are meant to represent the Middle Passage Slave Trade that brought enslaved Africans to the Americas. However, seigaiha is a Japanese word that means “blue ocean waves.” It describes a particular design element in Japanese art that consists of concentric circles symbolizing waves. It is obvious Japan had absolutely nothing to do with the Middle Passage Slave Trade, so why did Biggers bring Japanese culture into his denunciation of slavery?

The “unique wave illustration” was not “designed by Biggers.” It was hand drawn by New York based artist Mariko Garcia and based on the Japanese “Nami” design representing powerful, churning ocean waves. Garcia titled her drawing “Rough Waves” and made it available on merchandising sites like Adobe, Shutterstock, and Pixers.

On those platforms you will not find her design listed under “Middle Passage” or “Slave Trade.” Apparently Biggers took Garcia’s Rough Wave textile, had someone sew it up in flag form, then passed it off as his own design and claimed the turbulent waves represented the Middle Passage Slave Trade. How does this pass for significant art? Biggers’ Seigaiha flags have nothing to do with slavery, and everything to do with plagiarism.

Likely the most ridiculous thing about Biggers’ Oracle is that it is being juxtaposed to the celebrated masterworks associated with the Rockefeller Center building, particularly the works of American artists Lee Lawrie and Paul Manship. Those two virtuosos created works of irrefutable skill and artistry, and today their art continues to be enjoyed by the public at large for accomplished craft and timeless beauty. How tragic that postmodernism first obliterated, then blotted out the memory and concept of beauty in art. No one stands before an original Biggers to whisper in awe, “that is so exquisite, how did he do that?” Although some might say “why did he do that?” Poor betrodden Beauty, against her will she has been forced into a longterm hiatus.

In 1936 Lee Lawrie and fellow sculptor Rene Paul Chambellan created Atlas, a 45-foot-tall, seven-ton bronze statue for Rockefeller Center that stands outside the building at 630 5th Ave. Essentially Lawrie created sketches and models of the statue to be, and Chambellan translated them into sculptural form.

The ancient Greeks believed Zeus, King of the Gods, condemned Atlas to hold up the sky with his shoulders for eternity. Lawrie and Chambellan depicted Atlas shouldering the sky by showing him bearing an enormous armillary sphere, the astronomical tool representing the heavens used by the Greeks.

On the celestial sphere you can see the Greco-Roman planet symbols for Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune.

Lawrie was one of the greatest sculptors of his day. His creations include architectural sculptures on the 1926 Los Angeles Public Library, and the 1939 bas-relief bronze doors on the John Adams building of the Library of Congress, Washington DC. Those doors included twelve figures depicting gods or heroes from ancient Mexico, China, India, Mesopotamia, Greece, Persia, Germany, and North America, all associated with the advent of writing. The artworks are an example of the “diversity and inclusion” today’s radicals say are lacking in the American cultural landscape.

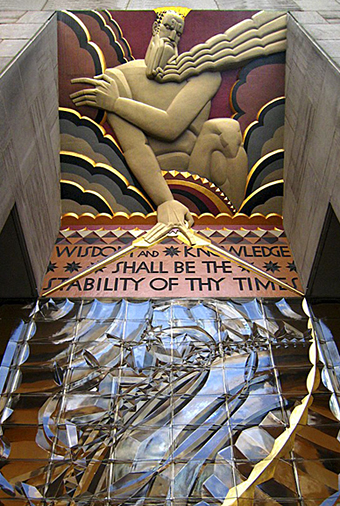

Lee Lawrie created a second tour de force for the Rockefeller Center—relief sculpture panels known as Wisdom with Sound and Light that sit over the main entrance doors.

Lawrie carved the panels from limestone and collaborated with artist and polychromist Leon V. Solon, who painted and gilded the sculptures. Solon advocated Architectural Polychromy, the decorative painting of stone buildings to make them more elegant and harmonizing. He made the following statement regarding his work:

“Color is a terrific force when introduced into an architectural combination, and is capable of producing an effect upon the observer equaled only by the fascination which firearms possess for small boys.”

The politically correct will no doubt be horrified. Perhaps they shall cancel the artworks of Lawrie and Solon.

In 1934 American artist Paul Manship created the statue titled Prometheus, seen in the lower Plaza of Rockefeller Center. His pre-Olympian Titan god of fire is an 18-foot-tall, eight-ton bronze sculpture gilded with gold. The ancient Greeks believed Prometheus created humanity from clay. It is said he stole fire from Zeus, and gifted it to humans.

Enraged by that act Zeus condemned Prometheus to eternal torment by having him bound to a rock, where an eagle would come to eat his liver. The liver grew back every night, and each morning the eagle returned to feast.

Manship depicted Prometheus clutching the stolen fire in his right hand as he falls through a gigantic ring representing the heavens. The red granite wall behind the statue is inscribed with the paraphrased words of the ancient Greek playwright Aeschylus: “Prometheus, teacher in every art, brought the fire that hath proved to mortals a means to mighty ends.”

And what fire does Biggers bring? His Just Us mural on exhibit at the Rockefeller Center is a confused muddle in every sense. It is a Photoshop creation printed on an inkjet printer. It has all the gravitas of a pamphlet printed at a commercial print shop; its political message is baffling as well. During the 60s, radical civil rights activists said American justice was accessible only to white men, referring to US jurisprudence as “Just Us.” But who speaks the phrase in the Biggers mural, oppressor or oppressed? Is it a badge of honor or a victim’s fear? Why do the words hang in the heavens like an irreligious joke? Are we expected to be impressed with ambiguity? Just Us is too arcane to be a political statement, and even less noteworthy as a mural. Muralism has fallen from its once commanding position into the abyss of lowbrow kitsch, graffiti, and other postmodern inanities. That is where you find Biggers.

Biggers believes his Oracle bronze statue is a necessary companion to Lawrie’s and Manship’s bronze statues, because he imagines he has provided the missing puzzle piece of the African experience. Without naming a particular building or artwork, Biggers told the media that all throughout Rockefeller Center, “there are smaller symbols of the triangle trade and the slave trade. You see references to tobacco and cotton and sugar.” The press published his allegations without question or objection. You might think an explicit accusation that racist iconography is part of the architecture of Rockefeller Center might be cause for a journalistic investigation. Nope. Journalism is dead.

Biggers was alluding to the Rockefeller Center’s British Empire Building, designed by Raymond Hood to house British governmental and commercial offices.

In the early 1930s artist Carl Paul Jennewein created Industries of the British Empire, a huge relief panel in bronze for placement above the entrance door. The 18-foot high by 11-foot wide, blackened patina bronze panel was decorated with nine gilded allegorical figures representing the vital industries of the British Empire—Salt, Wheat, Wool, Coal, Fish, Cotton, Tobacco, and Sugar.

Eight of the laborers had tumbling gilded letters spelling out their industry placed next to them. European laborers from the British Isles, Canada, and Australia were identified with fish, coal, wool, and wheat.

Biggers might be shocked to find Jennewein identified those in his bronze panel working with sugar, tobacco, and salt, as workers from the subcontinent of India, not African slaves from the Middle Passage Slave Trade.

In 1792 the British Crown found it cheaper to produce sugar in British India than on Caribbean islands. Jennewein’s artwork showed an Indian man working with sugar cane, an Indian woman with tobacco plants, and another carrying a bag of salt. Jennewein’s artworks unintentionally exposed colonialism at work in India—but Biggers payed no attention.

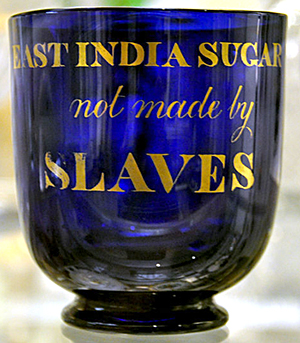

He will not tell you that in 1791 British citizens by the hundreds of thousands were buying sugar from India where slavery was not used, and were spooning their Indian sugar out of abolitionist bowls inscribed with “East India Sugar not made by Slaves.” American abolitionists did likewise.

If Biggers does not understand the importance of salt in India’s Independence movement against British colonialism, he should read a few books on the subject.

Of the nine gilded allegorical figures in Jennewein’s bronze, only one portrayed an African—a woman working with cotton. Is Biggers also unaware that in the late 1800’s African cotton fed the British textile industry, and slaves from the Triangle Trade had nothing to do with it?

In Sudan the British Empire defeated Islamic fundamentalist leader Muhammad Ahmad in 1898, he claimed to be the Mahdi (“Guided One”), the deliverer and restorer of true Islam. His Mahdist army had established an Islamic State in Sudan that stretched from the Red Sea to Central Africa. After vanquishing the Mahdi and his caliphate, Sudan became a source of cotton for the growing British textile industry; it also gave access to the Nile, expanding British markets and suppliers.

Recall that Biggers said relief sculptures in Rockefeller Center depicted “symbols of the triangle trade and the slave trade.” But the history of colonialism and empire is complicated. During the Triangle Trade Great Britain sent trade goods such as cloth, iron goods, guns, and rum to Africa.

Many powerful African empires like the Kingdom of Benin (1440-1897), traded enormous numbers of black captives for those goods. The estimated number of captive slaves traded away by various African empires reaches as high as 20 million.

The Kingdom of Benin sold slaves to British, French, and Portuguese merchants for over 200 years. The slaves were shipped to the West Indies and the Americas. From England’s 13 Colonies, rum, iron ore, timber, furs, rice, indigo dye, and other goods were shipped to Great Britain, beginning the process anew.

Nothing I write here denies the ugly blot of the Middle Passage Slave Trade and the inhuman treatment of African people at the hands of slave traders. The empires of Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Belgium, and Spain mercilessly partitioned and exploited Africa. However, the Transatlantic Slave Trade would have been impossible without the partnership of slave trading African empires, who enslaved fellow Africans for material gain.

If an artist is going to confront the monstrous history of slavery, then fabrication and calumny are not the colors to paint with. It should also be remembered that France abolished slavery in 1794, Great Britain did so in 1833, and on December 6, 1865, slavery was ended in the United States—and the cost was the death of some 365,000 Union soldiers. Modern day slavery continues to exist in the world today, but “progressive” artists have very little to say about it.

What does Mr. Biggers say about the nation of Mauritania, also known as the Islamic Republic of Mauritania, where the “peculiar institution” bleeds into the present. Historically Arab Mauritanians enslaved the Haratin black Mauritanians. Mauritania gained independence from France in 1960, yet did not end slavery until 1981; it was the last country on earth to abolish slavery. According to the BBC it did not criminalize slavery until 2015. In 2017 the BBC reported 600,000 Mauritanians were held in human bondage. Despite all of that Mauritania was allowed to join the UN Human Rights Council in 2020!

So, where are the paintings, videos, audio recordings, murals, flags, and statues by Biggers exposing modern day chattel slavery in Mauritania? It is so much easier to bash Western Civilization for the umpteenth time, while giving an encore recitation on the crimes of “whiteness.”

Biggers’ racialist politics are barely camouflaged by postmodern aesthetics and artspeak; he stands with those who want to “decolonize” the art institutions of the Western world. They are convinced American and European Classical art are linked to white supremacy and its “colonial project.” A writer at the leftist art periodical Hyperallergic succinctly made the point: “America’s encyclopedic museums originated from worldviews not that different from those of today’s white supremacists and nationalists.” Another frenzied dilettanti from the same journal proposed the abolition of museums because they deploy violence “against black bodies, brown bodies, gender non-conforming bodies, colonized bodies, queer bodies, immigrant bodies, disabled bodies, poor bodies, as well as violence against the cultures that these bodies create and move through.”

I am horrified that a layer of contemporary leftists are arguing for the abolishment of museums in Europe and America. They insist museums be “reimagined” (I have come to loath that word), because they think those institutions are “at war” with people of color. That canard has a familiar ring, it reminds me of the Khmer Rouge communists who seized Cambodia in 1975. They declared they would “abolish, uproot, and disperse the cultural, literary, and artistic remnants of the imperialists, colonialists, and all of the other oppressor classes. This will be implemented strongly, deeply and continuously.” [¹] The Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot called the reign of terror “Year Zero.” And so they “reimagined” Cambodia by smashing every vestige of bourgeois society, art, culture, religion, and old traditions. Those “corrupted by imperialistic ideas,” and there were some 1.3 million of them—were executed. It was Pol Pot’s “Great Reset.”

Biggers and his art world allies want you to believe there has been a failure to “understand” classical European art as a “white-washed” history where people of color have been ignored. The decolonize art crowd maintains that classical European sculptures of white marble were once painted in bright colors, true—if speaking of the marble and bronze sculptures of ancient Greece and Rome, but that hardly encompasses the total output of Europe’s classical sculptures. Some insist the Renaissance aesthetic was a “mistake”! Roman statues unearthed in the 15th century were stripped of color by time and the elements, so artists of that period mistakenly deduced the statues had always been white. From the racialist view it follows that from then on, creating white marble statues was only “normalizing whiteness.”

Renaissance artists had good reason to sculpt from white Carrara marble, mined in Italy since the days of ancient Rome—it had nothing to do with race. Freshly quarried Carrara marble is generally soft and easy to carve, it possesses minimal veining which makes the surface consistent, it has a fine grain that captures detail, and it can be polished to extraordinary effect. Most important of all, white Carrara marble has a certain translucency, making it perfect for modeling the human form. Michelangelo (1475–1564) used Carrara marble to carved his Pietà and David masterworks. Renaissance artists made an aesthetic leap by introducing a natural, realistic treatment of subjects, infusing them with emotive power. Form, texture, the play of light across marble, was thought essential. The idea of painting such statues was unthinkable.

Biggers and the coterie around him will likely never mention Edmonia Lewis (1844-1907). She was the first African American sculptor to gain national and international recognition for her sculptures.

She studied sculpture in Boston, where she met abolitionists like John Brown and Colonel Robert Gould Shaw—commander of the Union Army’s 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment composed of free black men.

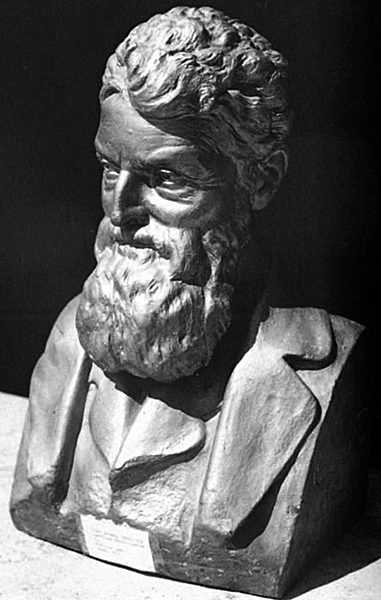

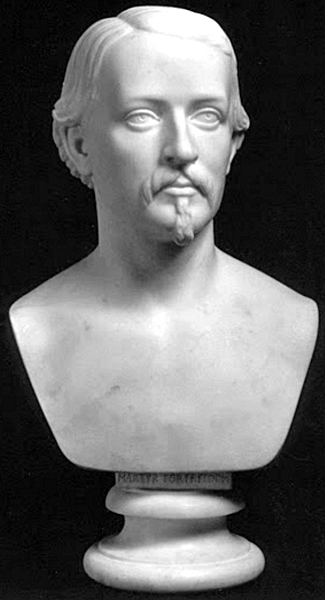

She created portrait busts of John Brown and Colonel Shaw after their deaths. Brown was hanged for treason on Dec. 2, 1859 for his raid on the Harpers Ferry federal armory. The US Civil War began on April, 12, 1861, and Lewis created her plaster sculpture of Brown in 1864. A year later the American Civil War ended on May 9, 1865.

On July 18, 1863 Colonel Shaw and the men of the 54th, attacked Confederate held Fort Wagner in South Carolina. They were cut to ribbons by fire from the 1,700 Confederates in the fortress. Of the six hundred soldiers in the 54th, 250 were killed or wounded.

Colonel Robert Gould Shaw was killed on the ramparts while fighting in hand to hand combat. At the bottom of her marble portrait of Colonel Shaw, where the bust meets its pedestal, Edmonia Lewis carved the words, “Martyr For Freedom.”

A surviving member of the 54th, William Harvey Carney, received the Medal of Honor for his gallantry. He carried the American flag into combat and planted it on the parapets. When the Rebels forced the 54th to retreat under fire, he brought the flag back with him despite being shot four times. Carney never let the American flag touch the ground.

Lewis’ portrait bust of Colonel Shaw was purchased by the Shaw family, who gave the artist permission to make plaster replicas of the bust to help advance the Union cause; Lewis created and sold 100 of these for five dollars each.

On a related note, the American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907), created the bronze Memorial to Robert Gould Shaw and the Massachusetts Fifty-Fourth Regiment that sits at the edge of Boston Common in Massachusetts. At a Black Lives Matter protest on May 31, 2020, the monument was vandalized with giant spray-painted red and black graffiti that read; “RIP George Floyd,” “All Cops Are Bastards,” “BLM,” and “FUCK 12” (twelve being a reference to police). Who shall tell the spirits of the 54th that Black Lives Matter defiled their monument?

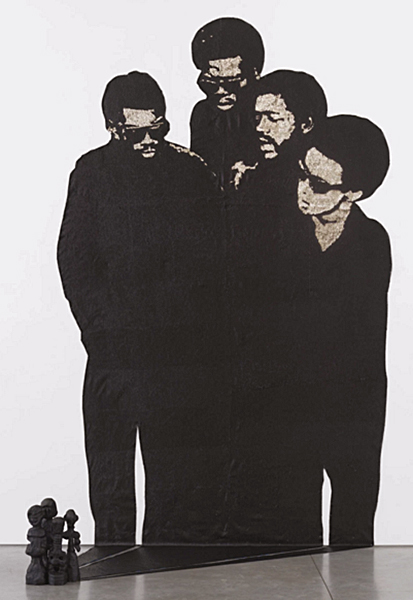

I am unsure if Sanford Biggers is exhibiting his 2017 artwork titled Overstood at the Rockefeller Center, but it is worth mentioning to fully understand his body of work. Wrapped in his “African cultural perspective” cloak, Biggers uses the Jamaican patois word “overstand” to replace “understand” in the title. The artist described his work with the following:

“Inspired by a photo of a 1968 Black Panther Party protest and emanating from hand carved power objects on the floor, four larger than life elders look down on centuries of systemic disenfranchisement, pathological extrajudicial practices of the US government towards Black Americans, and the culture that allows these to persist. They witness, stand over and “overstand” that change must come.”

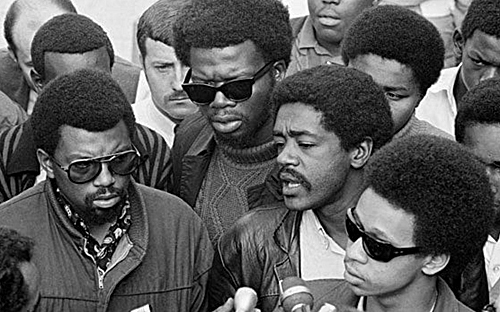

There are a number of problems with the artwork and its statement. Biggers did not credit Associated Press photographer Ernest K. Bennet for the photo of Black Panther Party co-founder Bobby Seale and his militant comrades; who were not all Panthers.

It can be argued that not crediting Bennet is plagiarism, as with Biggers’ Seigaiha flags. Some will say fair use laws allow for such artistic practice, but I contend it simply shows Biggers has no talent or aptitude for drawing.

You might think an artist is expected to show a genius for the delineation of form by way of line, shading, and tone, but the art establishment of today insists drawing is passé, unless talking about meaningless scrawls and scratches.

The real headache regarding Overstood is its misrepresentation of the Black Panther Party and the artist’s cultural nationalist political baggage. Which brings me to the “hand carved power objects” Biggers has his “Panthers” springing from.

Plainly speaking the Panthers were not practitioners of religion, African or otherwise; they were adherents of Marxian dialectical materialism, not African spiritualism. Yet Biggers shows them, not only as creations of African spirits who have conjured them up, but as supernatural beings in some ethereal African afterworld. Clearly, Biggers is far-removed from the thoughts of Panther leader Huey P. Newton, and in alignment with the black supremacist cultural nationalism of Maulana Karenga. To understand the quandary lets review some historic facts.

The Black Panther Party (BPP) embraced revolutionary socialism and defined itself as the “vanguard of the revolution.” It held political education classes where party members were required to read and understand works like: The Wretched of the Earth by Frantz Fanon, The Last Stage of Imperialism and Class Struggle in Africa by Kwame Nkrumah, The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Black Bourgeoisie by E. Franklin Frazier, The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx, and Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung.

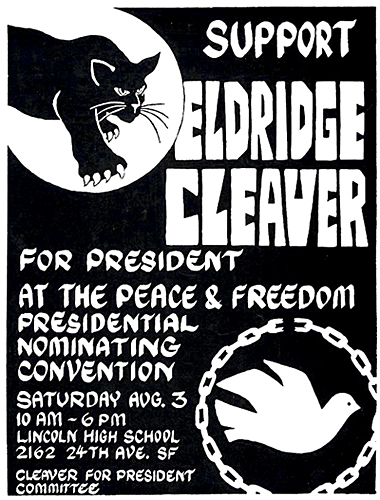

The Panthers expressed solidarity with socialist Algeria, and the communist regimes of China, Cuba, North Vietnam, and North Korea. The BPP was not a black supremacist organization, it sought working relationships with all races. In 1968 its Minister of Information, Eldridge Cleaver, ran for president on the California Peace and Freedom Party.

The Panthers opposed the cultural nationalists of the US Organization, founded in 1965 by Ron Everett, who took the Swahili name of Maulana (master teacher) Karenga (keeper of the tradition). Karenga wanted no alliances with whites, insisting that a cultural return to Africa would restore black identity and bring deliverance to American blacks.

Followers wore African clothes, spoke Swahili, and gave themselves African names. In 1966 Karenga invented an African harvest festival he called Kwanzaa. His objective was to “give blacks an alternative to the existing holiday of Christmas and give blacks an opportunity to celebrate themselves and their history, rather than simply imitate the practice of the dominant society.”

Karenga elaborated, “You must have a cultural revolution before the violent revolution. The cultural revolution gives identity, purpose, and direction.” U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris claims to celebrate Kwanzaa.

The leadership of the Black Panther Party, including Bobby Seale, referred to Karenga’s politics as “pork chop nationalism.” In a 1968 interview with The Movement publication of the Students for a Democratic Society, Newton described Karenga’s cultural nationalism as “reactionary” and “the wrong political perspective.” At the UCLA campus on Jan. 17, 1969, members of Karenga’s US shot and killed Black Panthers Bunchy Carter and John Huggins, because they ridiculed Maulana Karenga. Did the elders witness, stand over and “overstand” that act of political assassination?

One last comment on Biggers plagiarizing Bennet’s Nov. 21, 1968 photo. On that date Eldridge Cleaver delivered a speech at San Francisco’s California Hall. It was sponsored by his defense committee. It is somewhat likely Bobby Seale and his comrades were photographed at that event. Cleaver had been charged with attempted murder for an April 1968 shoot out with Oakland police where Panther Bobby Hutton was killed and two officers wounded. Sometime after his address Cleaver jumped bail to avoid imprisonment. He fled to Cuba, then to socialist Algeria, where the National Liberation Front had just won independence from France in 1962.

Some have implied Seale and fellow militants were photographed at the Third World Liberation Front student strike at San Francisco State College (Nov. 1968 to March 1969). Not likely, since Nov. 21st was not significant to the student action, despite two firebrands from the strike, Ben Stewart and George Murray being in the picture. Bennet’s photo is a conundrum. Cleaver’s speech and the student strike both happened in San Francisco, but the photo credit says it was taken in Oakland—across from the San Francisco Bay. There is no certainty regarding the event and location captured in the photo; it seems a detail lost to history. The only certitude is that Biggers concocted a narrative that he attached to a misappropriated historic photograph.

In conclusion, ever since Marcel Duchamp exhibited a porcelain urinal in 1917, artists have been subverting traditional sculpture. So, are the artists of today still yearning for the overthrow of classical sculpture? How is that even possible? What is left of traditional sculpture in the present day? How can the art of Sanford Biggers be considered “subversive” when it is embraced by galleries and museums, praised by art critics, and sanctioned by ruling class institutions?

Postmodern conceptual art, performance art, and installation art, rule the roost in present-day art institutions; that sphere supports Biggers. Traditional realist sculpture, painting and drawing is no longer spoken of in contemporary art magazines. It is shoved aside at art fairs and trendy galleries—one might find it cobwebbed in the basements of a few museums. It is not hyperbole to say realism has gone underground. It is time for a complete reversal of the situation.

As for the Rockefeller family and their namesake, the Rockefeller Center, there has been, shall we say, a rather prickly liaison with the art world over the years. I am certain Biggers does not know that during the Cold War of the early 1950s, the Central Intelligence Agency secretly worked with Nelson Rockefeller and other highfalutin members of the art world—including artists, to establish the dominance of American abstract art over the “Socialist Realism” of the Soviet Union. Yes, they even weaponized art. And today? Perhaps Biggers should do some reading on the topic.

So again the question, what is left of traditional art and sculpture? Not much, and regrettably artists like Sanford Biggers hope to fill the void. If toppling monuments to historic American figures and events subverts the mythos of the United States, then what mythology will supersede them? Mr. Biggers and his backers think they have the answer. Still I wonder. Instead of incessantly rubbing our noses in horrid things, why not create beauteous works of art, breathtaking works that uplift and unite people.

Would that be so difficult?

__________________

The Sanford Biggers exhibit at the Rockefeller Center, ran from May 5 to June 29, 2021.

FOOTNOTES:

1. George Chigas and Dmitri Mosyakov, Literacy and Education under the Khmer Rouge. The Cambodian Genocide Program, Yale University.