AI, the end of Illustration art

I recently came across an illustration of Elon Musk published on a popular news and commentary website. The credit for the likeness read “Image generated by ChatGPT.” A living artist was not employed to create the art. Instead, OpenAI’s generative artificial intelligence chatbot was the creator, and it’s not necessary to pay a machine to work.

Today all publications, left, right, and center, use Artificial Intelligence to generate illustrations. While AI is evolving, it can only plagiarize the entire history of human artistic achievement. If we allow the AI chimera to reach its apex, it will be a great loss for humanity.

These days, with all the talk of “America First,” you might think there’s an appreciation for historic American illustrators. After all, their artworks have graced the pages of US newspapers and magazines for lo these many years. Sad to say but, the average working Joe and Jane would be hard pressed to name an American illustrator.

Based on that tragic fact, I decided to create this modest gallery of artists who exemplify the impressive history of American illustrators. It’s a small collection of artists—there are countless others, and they’re all threatened by the dominance of AI.

First up on my roster of eminent American illustrators is Thomas Nast (1840-1902), otherwise known as the “Father of the American Cartoon.” Born in Germany, Nast came to the USA with his family when he was six-years-old. He became a US citizen in 1858.

To produce illustrations for newspapers, Nast used the typical process of his time. He would create a pencil drawing on an end-grain cut of boxwood, which is an exceedingly hard wood. When the sketch was done the artist gave the block to a skilled wood engraver.

Using the artist’s drawing as a guide, the engraver used steel tools (burins) to cut out the details and fine lines, turning the art into a block to be inked and printed on a printing press. Engravings on boxwood could withstand thousands of runs on a press without reductions in quality. However, in the 1890s with the development of photography and halftone printing, wood engravings became passé.

Nast was a relentless critic of William “Boss” Tweed, the corrupt chieftain of the Tammany Hall Democratic Party, the political machine that ran New York City. The artist’s searing depiction of Nast as The Brains behind Tammany Hall became a powerful symbol of corruption in the US.

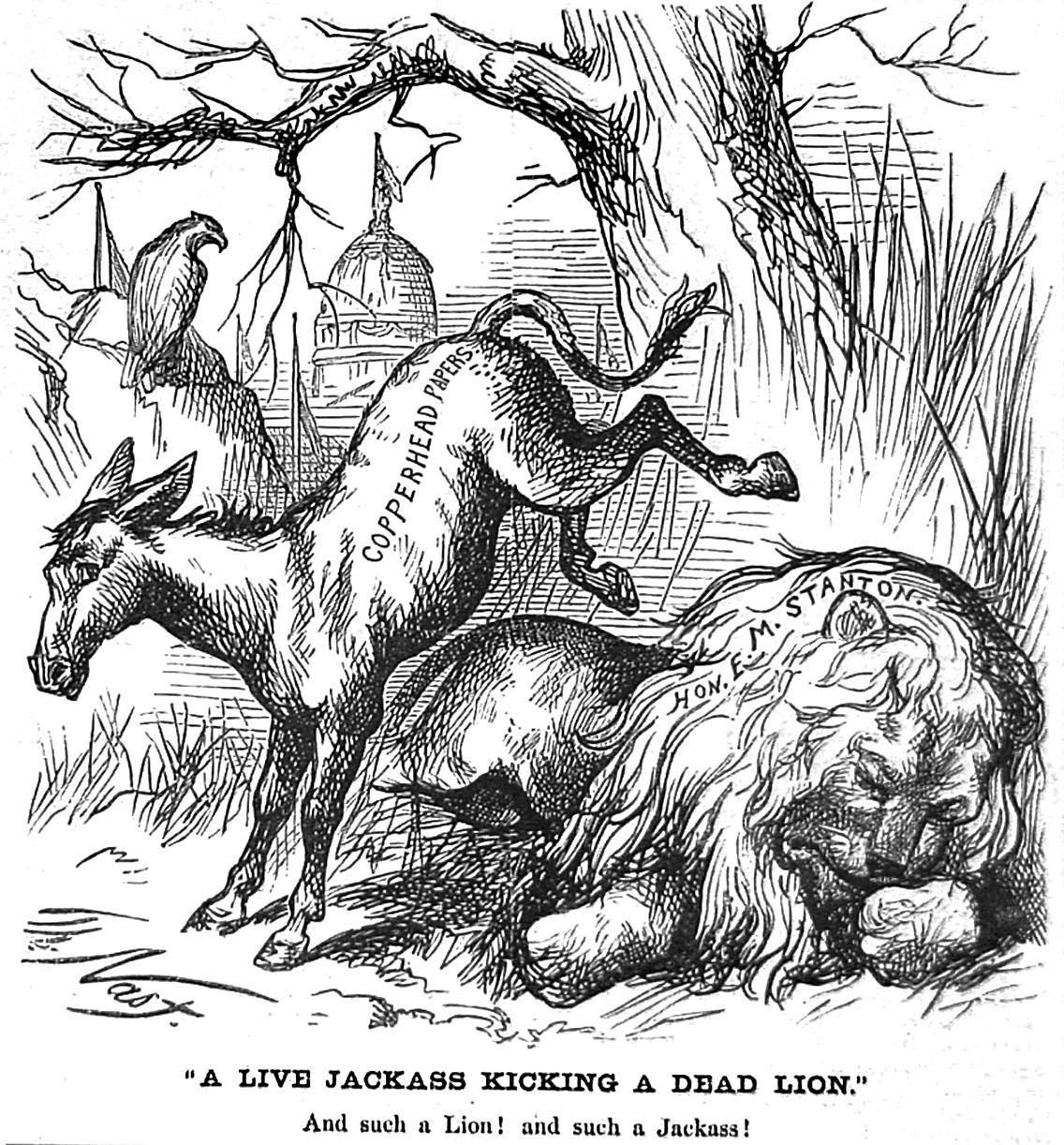

Through wood engravings like his 1871 “Merry Old Santa Claus,” Nast created the very image of Santa Claus we still embrace in the 21st century. Nast’s 1870 cartoon “A Live Jackass Kicking a Dead Lion,” immortalized the Donkey as the symbol of the Democratic Party, but the essential meaning of this graphic might be lost on contemporary viewers.

In the print a donkey is labeled “Copperhead Papers.” Anti-Slavery Republicans called Democratic Party members aligned with Confederates, “Copperheads,” comparing them to venomous copperhead snakes. The Copperheads encouraged desertion from the Union Army and opposed conscription. They advocated violent resistance to the Union cause and demanded President Lincoln be ousted as a tyrant. Sounds familiar?

The Copperheads were in control of a number of big city newspapers, hence the “Papers” label on the Jackass. In the cartoon the donkey is kicking a dead Lion labeled “Hon. E.M. Stanton.” The Honorable Edwin McMasters Stanton was a lawyer who served as Secretary of War under President Lincoln. Stanton died from chronic asthma in 1869, but Nast depicted the donkey still hoofing the dearly departed anti-Slaver in 1870.

Next up is painter and illustrator Winslow Homer (1836-1910). Born in Boston, Massachusetts, he was mostly self-taught, and began his art career as an Illustrator for Harper’s Weekly and Ballou’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion. Homer excelled at wood-engraving, and his detailed black and white prints translated beautifully to newsprint.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Harper’s Weekly sent Homer on assignment to create artworks that captured the realities of war. He was faced with a new phenomenon while documenting camp life among Union Army soldiers… the sniper.

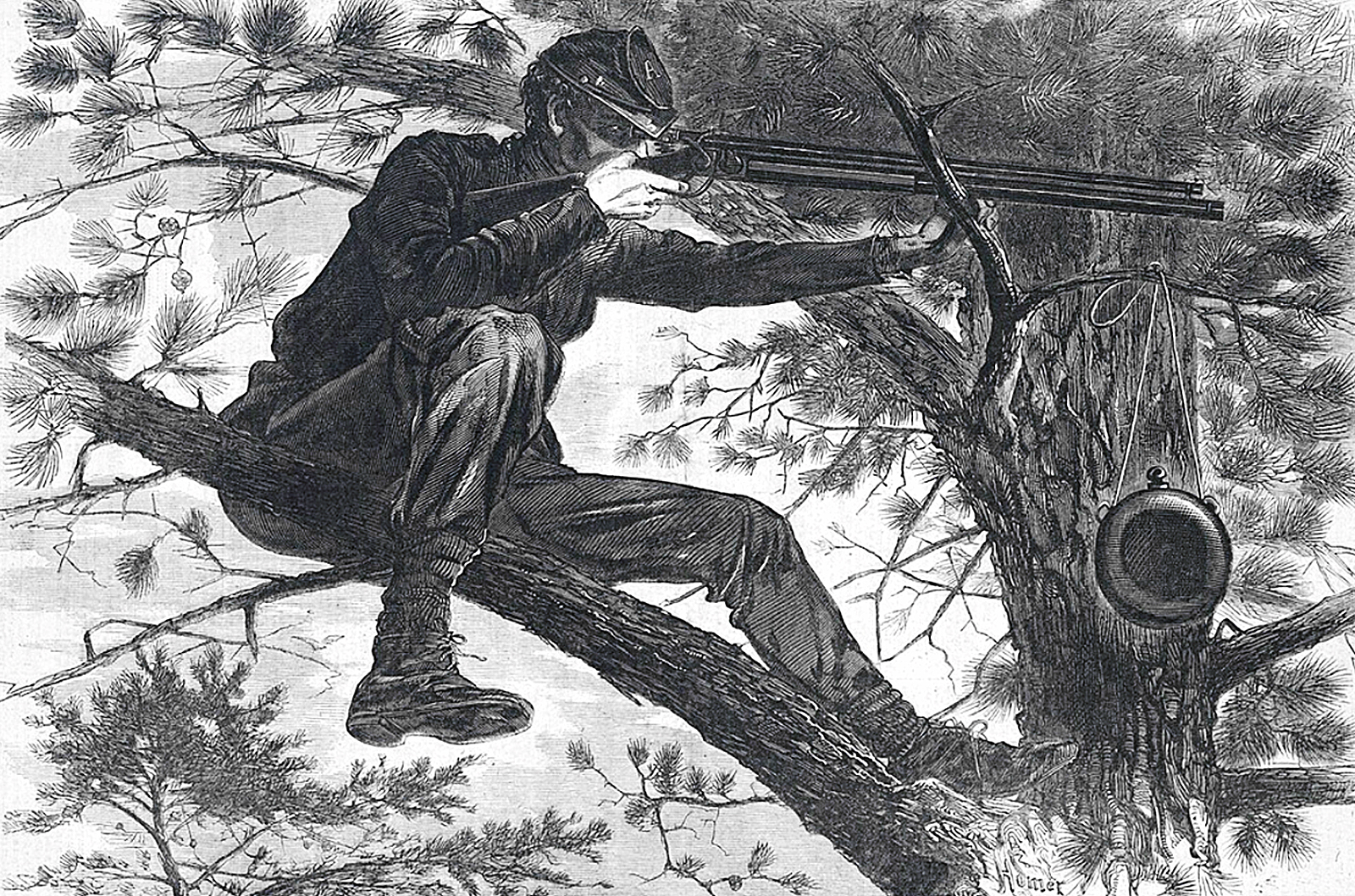

One of Homer’s most jaw-dropping wood engravings created while covering the Civil War was titled Sharpshooter. Published in the pages of Harper’s Weekly in 1862, it was a profoundly disturbing image of modern warfare. The artist recreated the image as an oil painting in 1863.

The artwork depicted a Union soldier looking through the telescopic site mounted on his “Sharps rifle.” Invented in 1848 by US gunsmith Christian Sharps, it wasn’t a rifle for infantrymen, it served the purpose of sniping. At the time that was thought to be an undignified and uncivilized way to fight. The first regiment of snipers was formed by the Union Army in 1860, since they carried the Sharps rifle they were called “Sharpshooters.”

Confederate snipers carried the British single-shot Whitworth rifle, an incredibly accurate rifle, but the Confederates had a limited supply of them. Meanwhile, factories in the North for Colt, Remington, Springfield Armory, and Sharps produced mountains of weaponry for the Union Army.

For his Sharpshooter wood engraving alone, Homer deserves a place on my list of American illustrators, but even a cursory look at his oil paintings and watercolor works assures his place.

Then there is the American realist painter Newell Convers Wyeth, better known as N. C. Wyeth (1882-1945). He created over 3,000 oil paintings in his lifetime and produced illustrations for 112 books, including classics like Treasure Island, Robin Hood, The Last of the Mohicans, and Robinson Crusoe.

There are dozens of Wyeth paintings I could have picked, but I singled out the oil on canvas titled, “‘Don’t let me fall,’ she begged.” The work illustrated a novel by American writer Herbert Quick, titled Vandermark’s Folly. Quick’s fictional tale told of a young pioneer man, Jacobus Vandermark, who journeyed West through the wilderness to start a township in Iowa. Quick’s book was illustrated with eight oil paintings by Wyeth.

The color palette and chiaroscuro of Don’t let me fall are transcendent, and the artist’s attention to detail is immaculate. The splotches and squiggles made by Wyeth’s paint-loaded brushes somehow communicate a delightful expressive realism.

N. C. Wyeth was slightly tortured by his good status in commercial illustration. He complained about his “accursed success in skin-deep pictures and illustrations.” He’s famous for having said, “painting and illustration cannot be mixed—one cannot merge from one into the other.” All the same, I don’t remember Wyeth for his advertising art, but for his “absolutely mad freedom and excitement with truth.”

The “Don’t let me fall” painting by Wyeth first appeared in the 1921 issue of Ladies’ Home Journal, where Quick’s pioneer tale was serialized. In 1922 the story was gathered together in book form. On April 18, 2024, Wyeth’s “‘Don’t let me fall,’ she begged” sold at a Modern American Art auction at Christies, New York for $189,000.

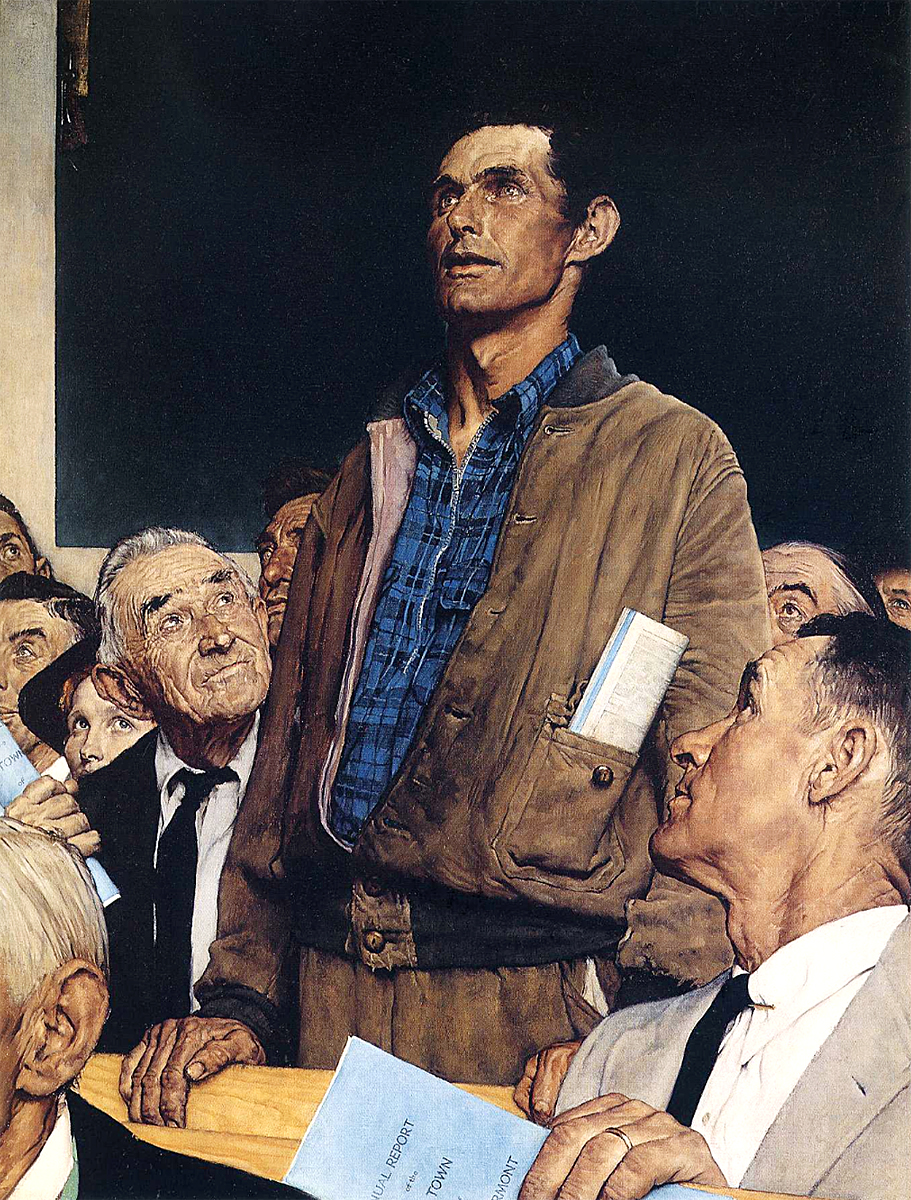

Who could forget Norman Rockwell (1894-1978). Well known for his realist oil paintings depicting American life, he was also an illustrator who created nostalgic illustrations for magazines like The Saturday Evening Post and Look. Rockwell was an iconic American painter of the 20th century.

Rockwell painted a series of oil paintings based on the State of the Union address given by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1941. In his oration the president articulated four fundamental rights that should be enjoyed by all. For each of the freedoms—Freedom of Worship, Freedom from Want, Freedom from Fear, and Freedom of Speech, Rockwell painted an interpretive image. To represent Rockwell’s body of work I selected his enduring masterwork, Freedom of Speech.

I’ve always loved Rockwell’s Freedom of Speech painting. It’s no surprise it continues to be adored by the American public. As an artist I appreciate the importance of the First Amendment to the US Constitution. While a sacred right to most Americans, some today insist free speech is “hate speech.”

Conservative activist Charlie Kirk was assassinated for publicly expressing his opinion. He was shot and killed on Sept. 10, 2025 by a leftwing gunman at an open-air rally at Utah Valley University in Orem, Utah. A number of Americans celebrated his death, yet the First Amendment protects speech, even discourse thought offensive. I’m certain Norman Rockwell would have been painfully embarrassed to hear that an American was killed for voicing his ideas. We should all be mortified.

The least known artist on this list is likely the American realist painter Gerrit Beneker (1882-1934). He created sympathetic paintings of working people; steelworkers, fishermen, construction workers, telephone operators, train engineers and railroad workers, and other blue collar workers involved in manual labor or skilled trades. Despite heroizing the American working class, he was far from being socialist-minded.

In 1918 Beneker began painting patriotic canvases for the US Navy. Those works were published as posters to encourage support for America’s role in World War I. His 1918 painting “Partners of Victory” is a good example.

Another Beneker oil painting from 1918 titled “Sure We’ll finish the job,” showed a smiling man in work clothes reaching into the pocket of his overalls for the money to buy a “Victory Liberty Loan” war bond. Four pins on his workwear showed he had previously purchased war bonds. To support the Allies in WWI, this poster was published to promote the sale of war bonds in the US—it sold over three million copies.

Beneker said of his oil paintings that were published as posters: “A poster should be a sermon in lines and colors. Its results are not directly obvious, no more so than the results of an inspiring sermon from the pulpit; but results in both are obtained, even if we can not see them immediately.”

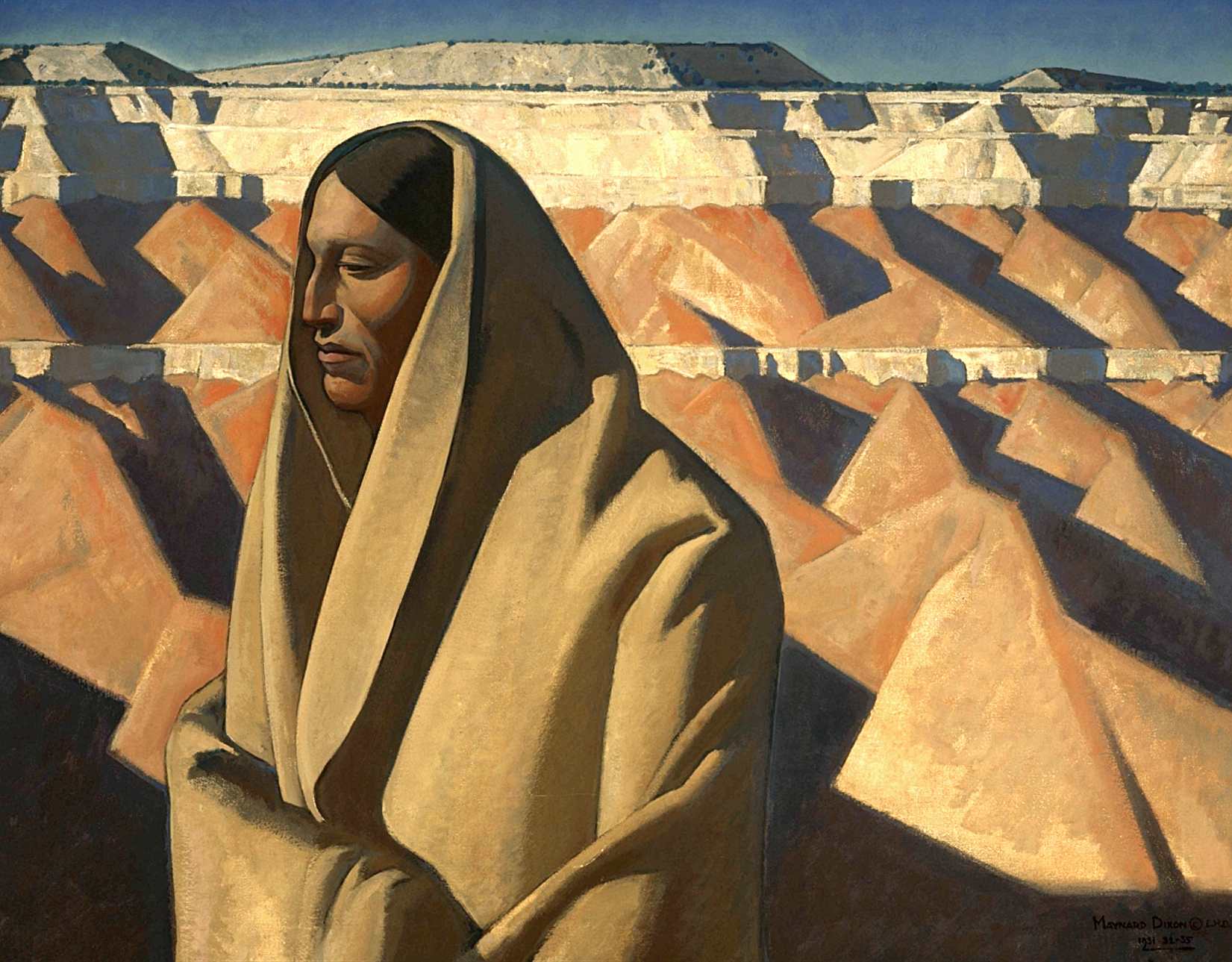

Last but not least is Maynard Dixon (1875-1946). Born in California he studied art at San Fransisco’s California School of Design in 1893. By 1900 he traveled across Montana, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, and New Mexico while painting encountered landscapes. He eventually settled in Southern Utah were he secured his legacy of being a painter of the iconic American West.

Dixon married photographer Dorothea Lange in 1920—she would find fame as a social realist photographer during the Depression years. Dixon was just getting by exhibiting landscape paintings in California, when the stock market crashed in 1929. The Great Depression battered America. Like most artists during the crisis, the couple were suddenly impoverished.

Dixon and Lange were profoundly affected by this period, their works became social realist in orientation as they documented the struggles of working people. Untold numbers of farmers and laborers from Oklahoma, Texas, Kansas, Colorado, and New Mexico who were fleeing drought, dust storms and the Great Depression, flooded into California.

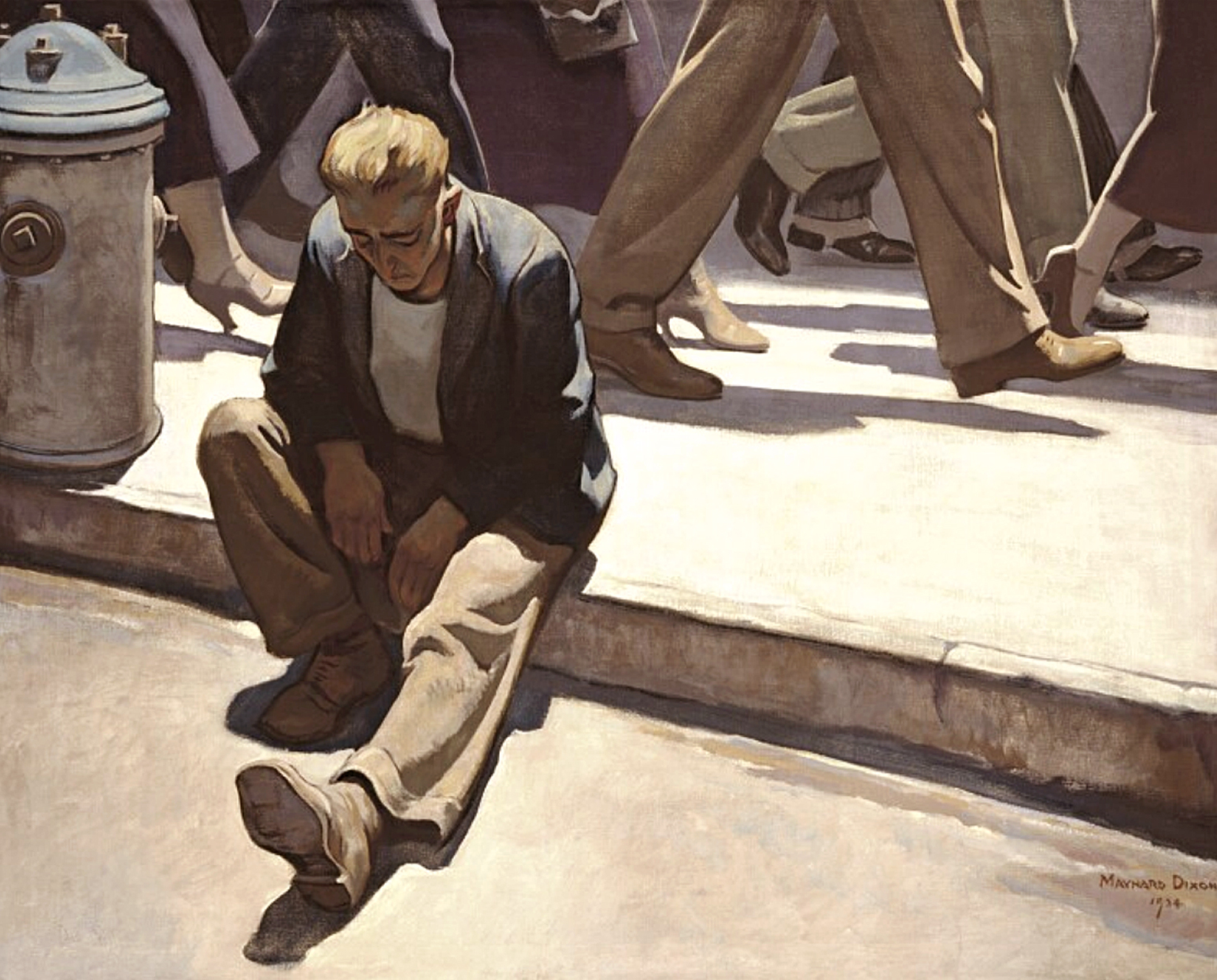

Dixon responded to the Depression by painting an unmatched example of American social realism. Seeing crowds of homeless men out of work in California, he painted “The Forgotten Man” in 1934.

In 1935 Dixon and Lange were amicably divorced. In 1937 Dixon married Edith Ann Hamlin, a realist painter and muralist from San Francisco. The two moved to Tucson, Arizona in ’39 but kept a summer home in Mt. Carmel in Southern Utah. When Maynard Dixon died on Nov. 11, 1946, his wife Edith scattered her husband’s ashes on a hill behind their house. A memorial plaque marks the spot.

The largest collection of art by Maynard Dixon is found at the Museum of Art at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah.

Today the Maynard and Edith Hamlin Dixon House and Studio in Mt. Carmel, is on the National Register of Historic Places. It is open to the public for tours. The home is near the magnificent Zion National Park, where Dixon painted several landscapes. I hope to visit the historic home and National Park one day.

With this essay I wanted to impress upon readers the importance of America’s illustration art. Over decades thousands of American artists captured national life with a multitude of unique styles, techniques, and perspectives. They put their imagination, passion, soul, and intellectual prowess into their works, capturing historic moments, experiences, social and political developments, and fashions.

At present art heritage is threatened by AI image generators, which produce images in seconds based on text prompts. AI doesn’t create, it plagiarizes. On command it scrapes up the entire international online collection of art, and in the blink of an eye repurposes the imagery. If your art is online it will be part of the treasure trove to be pillaged, without the slightest regard to copyright infringement.

If someone wants an image made to look like an authentic painting by Nast, Homer, Wyeth, Rockwell, or any other artist, they only need to type in a text prompt on an AI equipped computer. Gone will be craft, originality, inventiveness, and just plain astonishment. Humanity will be left with an endless computerized loop of imitation and plundering.

Critical thinking and reasoning have always been major aspects of art making, and integral to the appreciation of art. The building blocks of any civilization have always been the arts and sciences. That having been said, AI doesn’t think, it mimics, and computers are soulless machines.

All of the artists in my essay presented moral questions and ethical dilemmas for viewers to ponder—can we rely on lifeless machines to do the same? And what of the transcendental questions artists have contemplated for centuries, do we leave matters of spirituality to godless machines?

The Medium website published a somewhat critical article regarding AI titled “Hollywood Replaces 200,000 Workers with AI: Studios Stay Silent as Jobs Vanish.” The report delineates how AI is completely reshaping Hollywood filmmaking by replacing human labor with AI.

Oh irony of ironies. The credit line for the article’s illustration reads: “AI-Generated Illustration created by Coby Mendoza & Telum.” As far as it appears, Telum is an “AI Driven Boutique AdTech Digital Agency” in NYC and owner Coby Mendoza “leverages AI generative art.” Welcome to the future.

My solemn promise is this. I will never set aside my pencils and paintbrushes for the void of inhuman art manufactured by generative artificial intelligence. I will forever affirm that real art is made by human hands, with human heart and spirit.