The Last Supper of Western Civilization

This essay will broach the subject of The Last Supper, a controversial artwork by photographer Elisabeth Ohlson. Deemed blasphemous by many, it was exhibited at the European Union Parliament in Brussels, Belgium in May of 2023. I will contrast Ohlson’s irreverent photo with a brief overview of how visual artists in the West have portrayed The Last Supper—the final meal Jesus Christ shared with his apostles before being crucified.

I write this as someone born into a Catholic family; you might call me a “lapsed Catholic.” As a child I learned of the medieval, gothic, and renaissance art of Europe—artworks rooted in Christian thought. For me that remains a durable link to the Christian world, and European art from those periods continue to be a touchstone in my artistic philosophy.

To wit, I have always admired the 15th century painters of the Netherlands. Rogier van der Weyden and Jan van Eyck are favorites of mine. I was blessed to see Van Eyck’s 1434 The Arnolfini Wedding in London’s National Gallery.

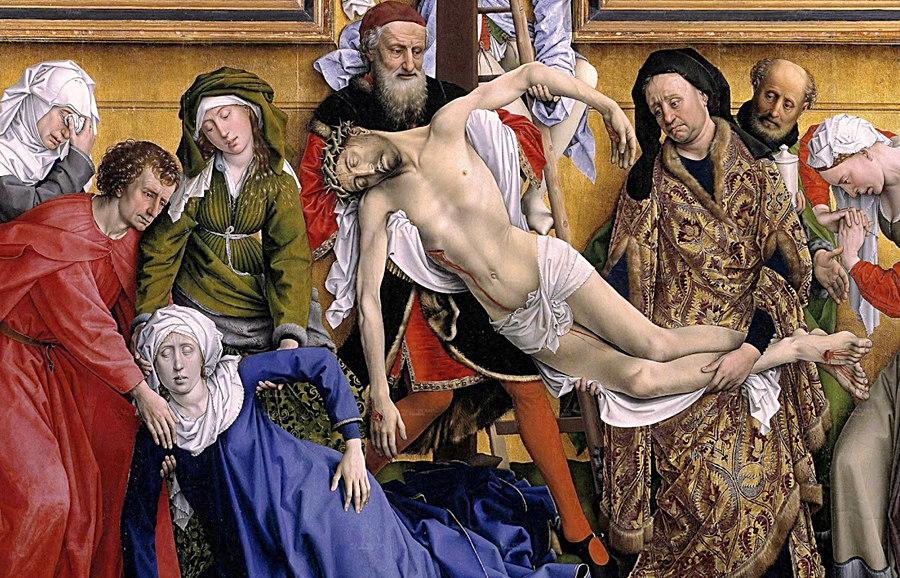

I was nineteen when I visited Spain’s Prado museum and came across the 1435 oil painting The Descent from the Cross by Rogier van der Weyden. It shook me to my core. The details in the painting are indescribable; there is stubble on the face of Jesus, the wounds on his body spare no detail, tears pour from the swollen red eyes of the Virgin, who has fainted—her position a mirror of the dead Christ. You can count the golden threads on one man’s robe; he is probably Joseph of Arimathea, the wealthy man who took responsibility for the burial of Jesus. The pathos of this painting is extraordinary.

By the early 1400s European artists had mastered painting with water-based tempera paints. In this period oil was introduced as a medium to carry pigments, and it brought dazzling new transparency effects to painting. Artists in the Netherlands took oil painting to grand new heights, no more evident than in Rogier’s Descent from the Cross.

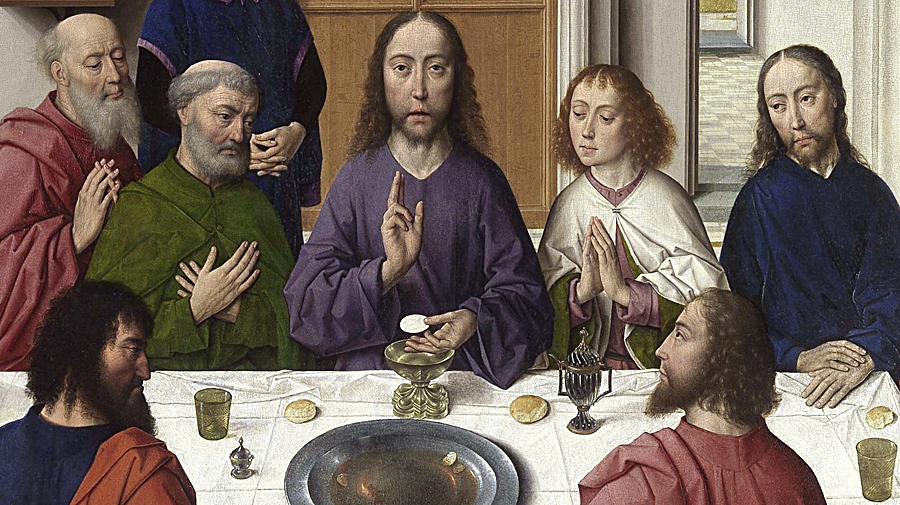

Sometime around 1415 Dieric Bouts was born in Haarlem, Netherlands. It is thought that he eventually studied under Rogier van der Weyden. Between the years 1464 and 1468, Bouts created his oil painting The Last Supper. It depicts Jesus and his twelve disciples having their last meal of bread and wine just before Christ is arrested and crucified.

The Last Supper is a beautifully composed and detailed work that places Christ and his apostles at a bench table covered with a white tablecloth. Jesus is the exact center of the composition; the painting would be one of the first in northern Europe to use the technique of linear perspective. Over an exquisitely painted silver goblet Jesus blesses the bread and wine consumed during the Passover meal. You can almost hear his words: “This is my body…This is my blood.”

Bouts placed John, “the disciple whom Jesus loved,” at the Messiah’s left. John’s hands are in prayer, he would be the one to ask Jesus for the name of the disciple who betrayed him. Judas Iscariot the betrayer, wearing a dark blue tunic and red robe, sits across from Jesus, his face in shadowy profile.

Bouts filled his painting with a profusion of details. The intricacy of the tiled floor and the architectural flourishes of the room; an elaborately painted candelabra hanging from the wood ceiling above Christ’s head; the windows in the room giving a peek at a medieval city in the Netherlands. Like every other artist of his time, Bouts painted biblical stories set in his own time and place.

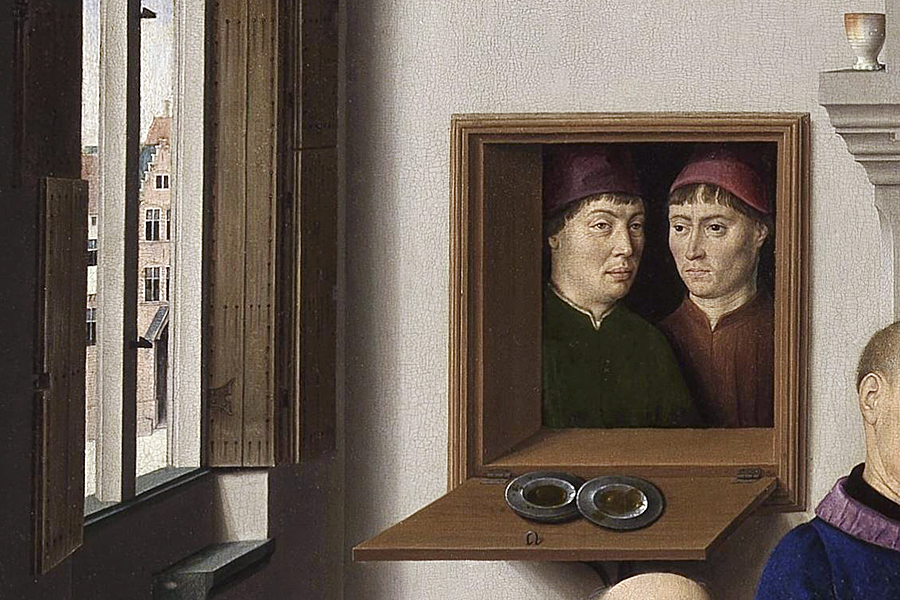

The Last Supper was commissioned to serve as the altarpiece in St. Peter’s Church in the city of Leuven. It would in fact be the central panel of a triptych painted on wood that Bouts titled, Altarpiece of the Holy Sacrament. Bouts honored those who contracted the painting—the Leuven Confraternity of the Holy Sacrament, by depicting two of its members viewing the proceedings from a window in the back wall.

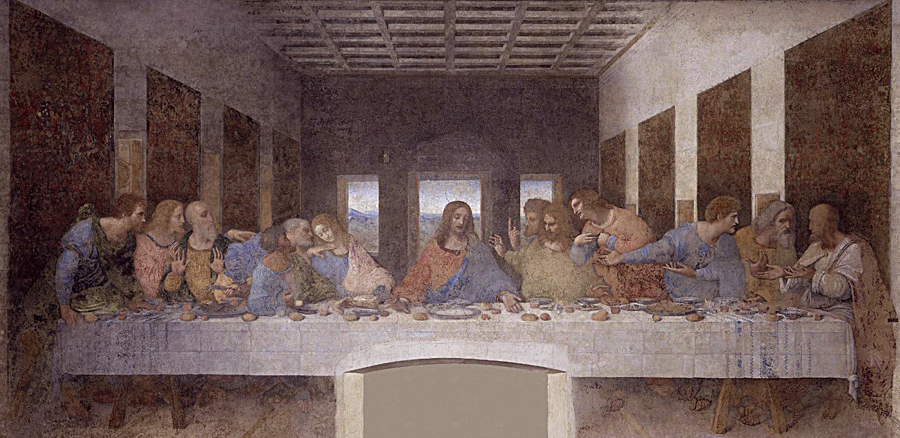

While many artists throughout the ages painted a version of The Last Supper, it is the High Renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci that is most associated with the Christian theme. Da Vinci painted his The Last Supper between the years 1495 and 1498, a good 30 years after Dieric Bouts painted his version.

Da Vinci depicted the disciples gathered around Jesus when he announced: “Truly, truly, I say to you, one of you will betray me.” However, Da Vinci broke with orthodoxy by making his painting a psychological study of the disciples reacting to the remark. In his composition the artist posed the Twelve Apostles in four groups, each holding three disciples. Da Vinci’s intention was to depict the disbelief, anger, and shock of the primary disciples.

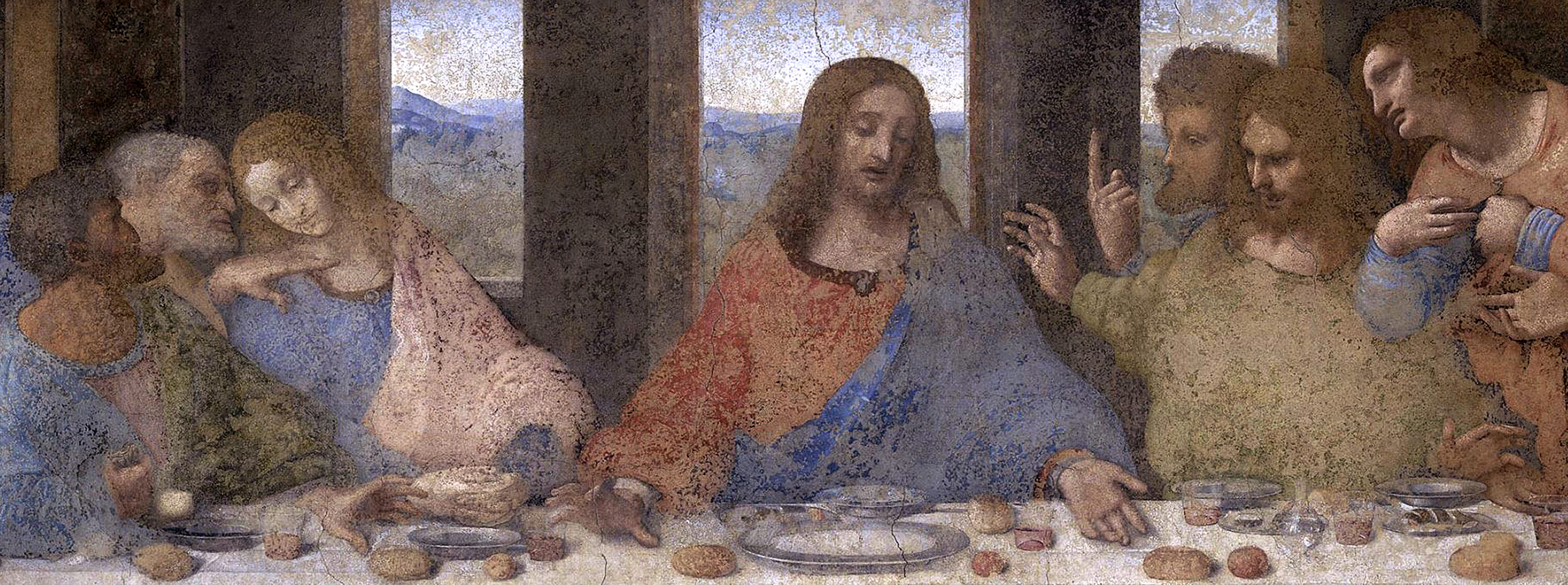

Peter, John, and Judas Iscariot form one of those groupings; they are seen at Christ’s right. The youngest apostle John is dressed in a blue tunic, his shoulder touched by Peter’s had in an emotive gesture, Judas sits on the left, his face obscured by shadow. The betrayer clutches a money bag in his right hand, and he is the only one to have his elbow on the table. Interestingly enough, his head is placed lower in the composition than anyone else’s.

Leonardo painted The Last Supper for a Dominican monastery in Milan named the Santa Maria delle Grazie. It was not a fresco mural where water-based pigment was quickly painted onto fresh lime plaster before it dried, Leonardo painted much too slowly for that. But it wasn’t an oil painting either. The artist tried something unconventional, he applied water-based tempera and oil paint to a dried gesso ground applied to the wall of the monastery. While the painting was a monumental artistic achievement, it was also a stupendous technical disaster.

Since the mural was not permanently affixed to the plastered wall like a fresco painting, moisture built up beneath the prepared ground causing the artwork to erode. Just years after completion paint began flaking off; the deterioration only increased over time. At one point a doorway was cut into the mural wall, the top of which juts into The Last Super table.

The monastery was even hit by an Allied bomb in WW2, but the mural survived. In 1999 it underwent a 20-year long restoration; colors that could not be restored were filled in with beige watercolor pigment. Nevertheless, The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci remains one of the most recognized and famous paintings in the world.

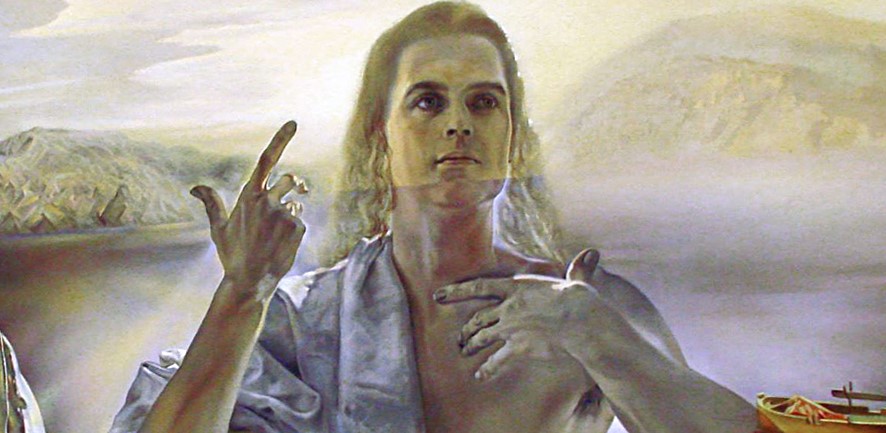

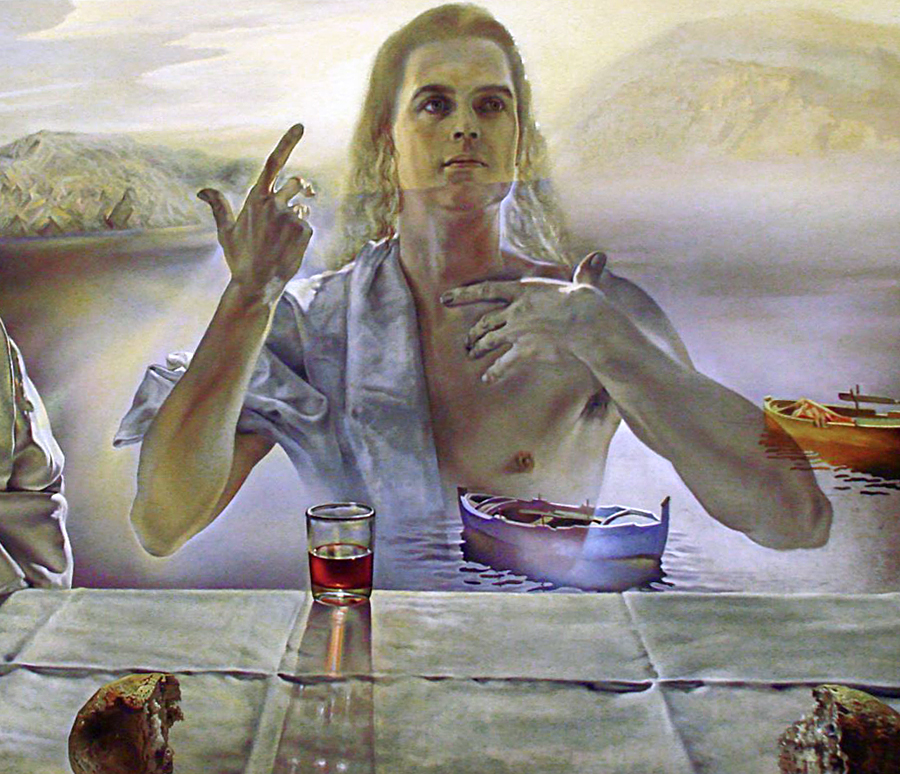

Skipping ahead to the 20th century, even the Spanish surrealist Salvador Dalí offered a take on The Last Supper in a 1955 painting he titled The Sacrament of the Last Supper. When he painted Sacrament he was well into expounding his “Nuclear mysticism” theoretics—a hodgepodge of Catholicism and his obsession with nuclear physics and geometry.

In the painting Dali presented Christ and the 12 Apostles sitting at a table, the disciples have their heads bowed in prayer, giving them anonymity and centering attention on Christ—who is semi transparent. The backdrop shows the coastal cliffs of Catalan, the autonomous region of Spain where the artist lived, and three boats of the fishermen who fished the seas. The Eucharist is simply denoted by a single glass of wine and a humble bread loaf divided in two.

Above the scene Dali painted heaven as a dodecahedron, reflecting the 12 Apostles. God the Father is also transparent and superimposed over the twelve faced geometric object. Dalí said of his painting:

“The first Holy Communion on Earth is conceived as a sacred rite of the greatest happiness for humanity. This rite is expressed with plastic means and not with literary ones. My ambition was to incorporate to Zurbarán’s mystical realism, the experimental creativeness of modern painting in my desire to make it classic.”

Dalí of course was one of the original surrealists that gathered around the radical French writer and poet André Breton, who wrote the Surrealist Manifesto in 1924. According to Breton the objective of surrealism was to create a “pure psychic automatism” that would spring from freeing artists of rationality, reason, and aesthetics. The stuff of dreams would fill surrealist art. Surrealism was influenced by DaDa, as well as marxist and anarchist ideas—Breton himself was a follower of the Soviet revolutionary Leon Trotsky.

The surrealists attracted an extremely diverse crowd of malcontents; Giorgio de Chirico, Man Ray, Joan Miró, Marcel Duchamp, Yves Tanguy, Max Ernst, Dalí, and others. With time Breton viewed Dalí as a money chasing opportunist—which he certainly was, and branded him with the monicker of “Avida Dollars,” an anagram meaning “eager for dollars.”

Since Dali supported capitalism and didn’t back the 1936 leftist revolution in Spain, Breton and his supporters expelled him from the surrealist group. It was a circle too diverse to remain cohesive (some avoided politics altogether), and so it divided into factions. Ironically, the original ideals and works of Breton’s group are largely forgotten outside of isolated artistic circles and academia, but the name Dalí became synonymous with surrealism.

In the post WW2 period, Dalí the surrealist became Dalí the devout Roman Catholic… with a surrealist twist. Religious iconography began to appear in his paintings and prints. His oil painting Madonna of Port Lligat (1949), was actually blessed by Pope Pius XII. Christ of Saint John of the Cross (1951) and Crucifixion Corpus Hypercubus (1954), are also good examples of the artist’s conversion.

Which brings us to the last entry in this article, an expository look at The Last Supper, a 1998 photographic version of the Biblical story. It was created by Swedish lesbian photographer Elisabeth Ohlson. Her controversial photo stirred an outcry when exhibited at the 2023 Plenary Session of the European Union Parliament in Brussels, Belgium.

The photo depicts a transgender Jesus wearing a white robe and high-heels. The trans Christ sports a painted on beard and sits at a cheap folding table with his 12 Apostles, except the disciples are transgendered persons and cross dressing homosexuals. One wears a black leather sado-masochistic outfit and platform heels, the disciples are drinking Champaign and eating chips.

As an example of today’s rubbishy postmodern shock art, The Last Supper is pretty much standard fair… but as sacred Christian art it is nothing more than an abomination. Isn’t the Ohlson exhibit a violation of the EU Parliament rules that exhibitions cannot “be offensive or of an inflammatory nature”? Unfortunately the answer is clear, the EU Parliament gave its approval to the provocation.

The Last Supper photo was exhibited in a restricted area of the EU Parliament building on May 2 through May 5, 2023, at an invitation only show. The photo is part of a body of work Ohlson titled Ecce Homo, Latin for “Behold the Man.” Comprised of photos depicting stories from the Bible, the figures portrayed are “sexual outcasts,” some dressed in black leather fetish gear. Selected Ecce Homo photos including The Last Supper made up the EU Parliament exhibit.

I should also note that on Dec 5, 2022, a Nativity scene was displayed in the European Parliament for the first and only time—but it was authorized solely as a “special exhibition.” Prior to that single display EU officials said the presentation would be “potentially offensive” to nonbelievers. The showing took place because in 2022 the president of the EU, Maltese politician Roberta Metsola, backed the Nativity scene proposal. Inexplicably, in 2023 the EU decided that Ecce Homo would not be “potentially offensive” to believers.

Only parliamentarians and their staff, or those with special permit badges were allowed to enter the Ohlson exhibition. The general public was barred entry. On Twitter the artist made the following statement regarding her Ecce Homo series:

“There are a lot of pictures of Jesus with heterosexual people. Millions, billions of paintings, famous artists. But this is just 12 pictures of Jesus loving the LGBT rights, so 12 pictures should not be so scary for them.”

Despite Ohlson’s assertion, Christian love and forgiveness is not the subject of her photos—she might wish it to be so, but the Christian community will still view her works as blasphemous. Pope Francis has referred to “gender theory” as an evil “dangerous” cultural aim that will “make everything homogenous, neutral. It is an attack on difference, on the creativity of God and on men and women.” When it comes to Christian theology, one might think a supreme pontiff just may know a thing or two about ecclesiology.

With the following remark Ohlson claims to believe in Jesus:

“I am a lesbian Christian photographer who believes that Christ represents everyone, including the sexual outcasts. Two thousand years ago Jesus taught love and justice and was killed for it. One of the accusations that led to his crucifixion was blasphemy, the same accusation that is brought against me and numerous other artists.”

Ohlson seems to see herself as a Christian martyr, going so far as to equate the crucifixion of Jesus with her being called a blasphemer. Consider Ohlson’s photo The Baptism of Jesus from her Ecce Homo series. Jesus was baptized in the Jordan River by John the Baptist, but Ohlson depicted the sacrament of initiation as a homoerotic baptism in a gay bathhouse. How could a true believer depict their savior in this manner?

What is the distinction between the photos made by Ohlson, and The Last Supper paintings created by Dieric Bouts, Leonardo da Vinci, and Salvador Dalí? While beauty, transcendency, and proficient technique motivated the painters, there was something else that inspired them… piety. Ohlson’s photo has none of those attributes, it is simply a political provocation meant to goad and offend.

As a postmodern provocateur Ohlson is familiar with insulting Christians. In Sept. 1998 she exhibited Ecce Homo in Sweden at the Uppsala Cathedral, the ecclesiastical center of Sweden and seat of the Archbishop of the Church of Sweden. Needless to say it was a huge controversy—The Last Supper and The Baptism of Jesus outraged many Swedes.

When she took Ecce Homo to Belgrade, Serbia in 2012 to be exhibited at the Centre for Cultural Decontamination, it appalled thousands of Christians. They gathered in front of the gallery wearing crosses, singing religious songs, and carrying posters of Jesus and Mary.

The exhibit had to be protected by armed riot police on a 24 hour basis, and 2,000 police were needed to control the protests. The leader of the Serbian Orthodox Church, Patriarch Irinej called the exhibit “blasphemous” and said it should be banned by the government. Serbia’s Islamic religious council, or Meshihat, joined the protests and made the following statement:

“It is neither art nor freedom of speech, because it consciously insults faith and believers. Muslims are just as offended by this sacrilegious representation of Jesus, as with sacrilegious representations of Muhammad the blessed.”

Since postmodernist artists possess little more than transgressive sensibilities, one should expect shenanigans like The Last Supper from them—but that does not explain why the elites of the European Union Parliament would condone the exhibit. The EU parliament rules are very clear:

“Cultural events and exhibitions shall not in any way undermine the dignity of parliament, be offensive or of an inflammatory nature, or likely to give rise to disturbances in the designated exhibition areas.”

The exhibition of Ohlson’s photos was organized by Malin Björk, who is a member of the socialist political party in Sweden known as the Vänsterpartiet (Left Party). Björk is also active in the EU parliamentary grouping called The Left, representing leftwing, communist, and socialist politicians of the 27 member states in the parliament.

In an online announcement of the exhibit of Ohlson’s photos, the Left Party stated: “Ohlson had her artistic breakthrough in 1998, with the exhibition Ecce Homo in a Swedish cathedral. In the show, Jesus was depicted together with LGBTQI people.”

The Left Party failed to mention that Ohlson’s “breakthrough” 1998 exhibit in Sweden angered many Swedes, or that the exhibit included The Baptism of Jesus photo of Christ in a gay bathhouse with his penis clearly visible.

As an American artist I cherish the First Amendment of the US Constitution, as it guarantees freedom of expression—something that is vital to every artist but not protected in many places in today’s world. The constitution of Belgium also assures free expression. That is precisely why I would never call for a ban of Ohlson’s works—but I can emphatically criticize her photos in the marketplace of ideas… which is also my right.

The few corporate news outlets that have bothered to report on the Ohlson exhibit, framed the controversy in terms of “right-wing parties,” or “far-right politicians” trying to censor Ohlson. Is the Pope a member of an extremist right-wing group? Is the humble and reverential global community of Christians nothing more than a mob of right-wing nationalists?

While the press displays bias against Christians, it pays little attention to the communists and socialists that organized the exhibit. Is the secular left now allowed to revise Christian theology? When do they get to reshape Islam into a politically correct religion?

Christianity is the largest religion in the world, with some 2.4 billion adherents around the globe. Even in Belgium where the EU Parliament is located, some 60% of the population still identifies as Christian. Obviously EU elites couldn’t care less if Christians would be offended by a transgender Christ. However, I suspect they would think “the dignity of parliament” might be undermined if The Last Supper photo—Heaven forbid—portrayed a transgender Mohammed.

Now that would be inflammatory.