Robert Rauschenberg 1925-2008

Robert Rauschenberg died at his home on Captiva Island, Florida on May 12, 2008, at the age of 82. Unquestionably there will be many eulogies written about the iconoclastic artist, and there’s not much that I can add in noting his accomplishments or his passing – save for the following. Rauschenberg always impressed me as being one of the more significant artists associated with the Pop Art movement, and my reason for feeling this is encapsulated in two well known quotes from him; “It is impossible to have progress without conscience” and “The artist’s job is to be a witness to his time in history.”

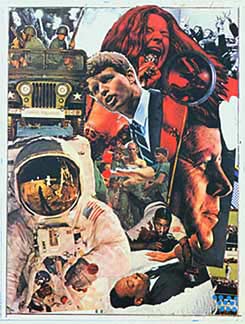

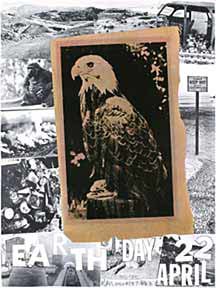

Rauschenberg stood apart from his Pop Art colleagues in using his skills to draw attention to social and political issues. His art activism certainly had its shortcomings, nevertheless, his many attempts at fusing art with social concerns were noteworthy. During the course of his life he created artworks that addressed the issues of war, racial equality, nuclear disarmament, apartheid, economic development, artist’s rights, and environmentalism – themes that all too few of today’s artists seem willing to tackle. While mainstream accounts of his life and art will focus upon his being a modern art innovator – reducing his achievements to mere questions of style and aesthetics – we should not forget that Rauschenberg was also a citizen artist deeply concerned with how his art could help change the world for the better.

Rauschenberg officially announced his Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange ( ROCI – pronounced “Rocky”), at the United Nations in 1983. It was a self-financed project that had as its mission the promotion of international peace and cultural exchange through collaborative art making. Under the auspices of ROCI, Rauschenberg visited and worked with artists in countries around the globe, using materials and skills found in each nation to create arworks that were donated to and exhibited in each host country. The culminating 1991 ROCI exhibit took place at the National Gallery of Art in Washington as part of the museum’s 50th anniversary celebration. The project would eventually visit 22 countries, including Mexico, Japan, Tibet, Venezuela, Germany, and Malaysia. It should also be noted that Rauschenberg’s ROCI project openly defied the Reagan administration’s Cold War policies by visiting the Soviet Union, Cuba, and China – but it would be in the South American nation of Chile where the artist would encounter the terror and dread behind the realpolitik of the Cold War.

In the book Robert Rauschenberg: Breaking Boundaries, author Robert Saltonstall Mattison wrote extensively about Rauschenberg’s harrowing and controversial days in Chile. On September 11, 1973, the democratically elected socialist government of Salvador Allende was overthrown in a military coup engineered by the U.S. government – bringing the dictator General Augusto Pinochet to power. Thousands of civilians were executed or simply “disappeared” by the military, and the bloodletting was still going on in 1984 when Rauschenberg arrived in Santiago, Chile. The artist recalled, “Armed soldiers were everywhere, and I was startled by the sounds of gunfire in the streets.” Rauschenberg had entered the country for a fifteen day visit just as Pinochet had declared a state of siege to crush popular protests.

According to Mattison, Rauschenberg “traveled to Chile without fully realizing the degree to which the dictator Augusto Pinochet’s repressive policies were tearing the country apart”, a fact that points to the artist’s naiveté. Rauschenberg “soon encountered students and political activists. He often met them secretly in church sanctuaries, where they told him of friends and relatives who had ‘disappeared.’ As a result of these experiences and against the advice of his staff, Rauschenberg went on his own to the outskirts of Santiago to photograph everyday life in the slums.” To his credit, Rauschenberg refused to be seen as a representative or agent of the U.S. government, and he shunned State Department help in arranging ROCI project details. It should be recalled that at the time the Reagan administration was moving to normalize its relationship with the military regime of Chile.

Many pro-democracy proponents viewed Rauschenberg’s trip to Chile as inopportune, and Donald Saff, a ROCI staff member in charge of logistics, recollected: “I never experienced as much anger about any artist’s project with which I have been involved as about ROCI Chile. The reactions from friends, fellow artists, and others was absolute outrage that Bob would stage a show with Pinochet in control.” Personally I would have counted myself amongst the critics, but Rauschenberg saw his Chilean exhibit as a radical gesture that would eventually help to open the path to democracy. Perhaps it did, though I’m still inclined to think of the ROCI Chile project as a mistake and one of the artist’s political shortcomings. On the other hand, I can’t deny Rauschenberg’s obvious sympathies for the people of Chile as they struggled for a free and open society.

While tributes to Rauschenberg recall the boldness with which he toppled art world sacred cows, let’s not forget the spirit he displayed in navigating the treacherous seas of national and international politics. If more artists today were willing to acknowledge and address social issues in their works – we’d all be in much better shape.