Abstract Art & The Cultural Cold War

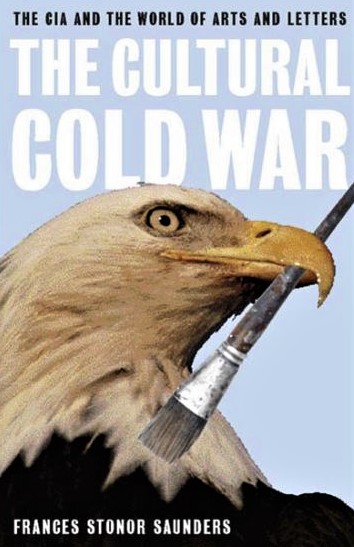

For those who still regard art as being above politics consider the following. The Central Intelligence Agency financed, organized, and assured the success of the American abstract expressionist movement, using artists like Jackson Pollock, Sam Francis, Willem de Kooning, Barnett Newman, Robert Motherwell, and Mark Rothko, as weapons in the struggle against the Soviet Union. Frances Stonor Saunders has presented this matter of public record in her well documented book, The Cultural Cold War – The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters.

Saunders informs us that during the height of the Cold War in the 1950’s, the CIA secretly promoted abstract expressionism as a means of discrediting the socialist realism of the Soviet Union.

The Agency’s scheme was really two fold, to shift the center of the art world away from Europe to the United States, and to create a national art that would extol unfettered liberty (without challenging the political status quo in the US of course). The CIA noted a group of little known upstart American artists and thought them perfect to help execute the strategy.

The abstract expressionists were attacking convention with their “action painting,” an avant-garde aesthetic that pronounced the act of painting to be more important than the results. These artists were the embodiment of an iconoclastic and fiery individualism, but their artworks contained a total absence of recognizable subject matter – not to mention overt politics.

They abandoned the concept of paintings offering narratives and instead favored a headlong rush into the mystical where agitated fields of color were the only message. Viewers could, and did, read virtually anything into such works.

Initially the abstract expressionists were received with scorn and contempt by art critics, members of the press, and conservative politicians. The movement was denounced on the floor of Congress as a communist conspiracy. Jackson Pollock was infamous for dripping, pouring, and hurling paint at the unstretched canvasses he laid out on his studio floor, so newspapers came to openly mock Pollock as “Jack the Dripper.” All the more surprising then that the CIA was determined to take this motley group of eccentric bohemians and transform them into the champions of Americanism.

The spy agency created and staffed an international institution they named the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF), and from 1950 to 1967 (when the front group was at last exposed as a CIA operation), the spook endowment had secretly bankrolled the abstract expressionist movement with untold millions of dollars. The CCF organized international gallery and museum exhibits and CCF operatives worked to persuade collectors, curators, and critics that Pollock, Rothko, Motherwell, et al, were the peerless artists of the age.

The CIA orchestrated the publication of a major article on Jackson Pollock in LIFE Magazine declaring him “the shining new phenomenon of American art,” and the “greatest living artist.”

The CCF brought action painting to the attention of Nelson Rockefeller whose family ran the New York Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Rockefeller was so enamored with what he saw that he referred to abstract expressionism as “free enterprise painting.”

Not surprisingly Rockefeller began his own action painting collection, furthering the largesse and esteem of the abstract expressionist movement. It is hard to imagine that the artists did not know where their money and support was coming from, but as Saunders put it in her book, “if they didn’t they were… cultivatedly and culpably, ignorant.”

Even after Pollock’s death in 1956 the Agency continued to promote his works by organizing posthumous exhibitions. The covert agenda suffered an unmasking in 1967 when Ramparts Magazine published revelations about the entire affair. President Johnson eventually ruled out domestic CIA programs and after 1967 the CCF was reorganized into the International Association for Cultural Freedom, which extended operations for another decade.

The spy agency’s stratagem had collapsed but an unalterable course of events had been set into motion. As is the rule with covert operations there were unforeseen consequences, or what critics call “blow back.” While the proposed target of the CIA was the communist ideal of art, it is not an exaggeration to say that unintended blow back included the undermining of figurative realism.

The CIA applied considerable muscle in its endeavor to support and advance the abstract expressionist movement, and in large part they were successful. Realism became passé as art critics focused on singing the praises of action painting. Galleries, museums, and private collectors spent appreciable fortunes on collecting abstract expressionist works while realist painters languished in obscurity.

It is a travesty for the art world to have forgotten this history… if they were aware of it in the first place.