Baskin: Graphic Force, Humanist Vision

The American painter, printmaker and sculptor, Leonard Baskin (1922-2000) once said “Art is content, or it is nothing.” As a teenage artist searching for role models, I discovered Baskin in the late 60’s – and I took his words to heart. A figurative realist shaped by the earthshaking events of the 1930’s, Baskin would first be recognized for his sculptures, but before long he was acknowledged as a master of lithography, etching, and monotype printing. Eventually, he would become most well known for a biting social criticism and a command of woodblock prints, works that would come to deeply influence me, so it pleases me immensely to know that the Portland Art Museum in the state of Oregon, is presenting Graphic Force, Humanistic Vision, an exhibition of some 50 prints and drawings by Baskin.

By the time the 50’s rolled around, message art from realists like Baskin fell out of favor in elite art circles, which were increasingly dominated by abstract painters and a predilection for non-narrative artworks. As the Portland Art Museum put it, “When movements such as Abstract Expressionism all but eliminated the human form in painting and sculpture, Baskin championed it.” Throughout his career and against all odds, Baskin persisted in creating realist artworks, but he was interested in much more than simply figuration. In the 1970’s he chastised the Photorealists for their disinterest in addressing social themes by saying: “Photorealism is the same thing as minimal abstraction. Both are unwilling to say anything about the nature of reality, about their own involvement with reality.” Two of Baskin’s most important works on paper will be on display at the Portland Art Museum, Man of Peace, and Hydrogen Man.

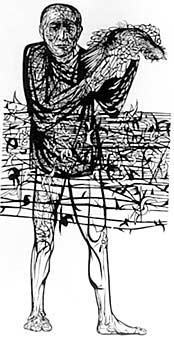

Man of Peace (1952) seems almost like an X-Ray of a partially clothed man, which is fitting considering the work was created at the dawn of the atomic age. Baskin’s subject is caught in barbed wire, and appears indistinguishable from it, in fact the man looks as though he could be made of wire himself. The subject holds a dove of peace that struggles to fly free. The print alluded to the genocide committed against the Jewish people by the Nazis, but seeing as how American society was mesmerized by a hysterical form of anti-communism at the time of the print’s creation, it’s easy to see how the art, and the man who created it, would come under suspicion. It’s instructive to remember that a year prior to Baskin creating Man of Peace, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were convicted in a U.S. court of spying for the Soviet Union, a conviction that fuelled the anti-communist witch hunts lead by Senator Joe McCarthy. A year after Baskin pulled his print – the Rosenbergs were put to death in the electric chair.

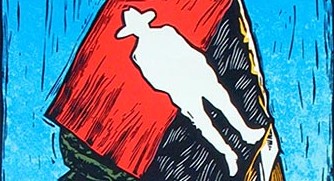

The U.S. exploded the first hydrogen bomb on March 1st, 1954. Baskin would respond by creating a life-sized woodblock print he titled, Hydrogen Man. The subject of the artist’s apocalyptic vision, a flayed and mutilated man, was a not so subtle reminder of the costs of atomic war and a warning that humanity was courting obliteration. Baskin said of his monumental prints, “Man has not molded a life of abundance and peace and he has charred the earth and befouled the heavens. In this garden I dwell, and in limning the horror, the degradation and the filth, I hold the cracked mirror up to man – and yet, and yet I hold man as collectively redemptible… he has endured.”