The Mexican Museum & Diego Rivera

December 8, 2013 marks the 127th birthday of the great social realist painter, Diego Rivera (Dec. 8, 1886 – Nov. 24, 1957).

As a member of the Arts and Letters Council of the Mexican Museum of San Francisco, I am pleased to announce that a free tour of Rivera’s famed Pan American Unity mural located in the Diego Rivera Theater at City College of San Francisco, will be conducted by The Mexican Museum in association with the Smithsonian Institution. The tour will be led by curator and coordinator of The Diego Rivera Mural Project, William Maynez, who will share his expertise with event attendees while regaling them with stories regarding the creation, meaning, and impact of Rivera’s mural.

The mural tour will take place on Saturday, November 23, 2013 at 11 am, in the Diego Rivera Theater on the campus of City College of San Francisco. Please RSVP for the event by sending an e-mail to: info@mexicanmuseum.org – with “Diego Rivera Mural Tour” in the subject head.

If you are anywhere near San Francisco, you will want to take advantage of the opportunity to see Rivera’s mural while listening to Mr. Maynez talk about its finer points. For those unable to attend, I offer the following photographs of the mural, which I took in 2011. Part of an ongoing presentation of my photos of the Pan American Unity mural, the following images are close-up details from the mural’s leftmost portion, a series of five panels Rivera titled, The Creative Genius of the South Growing from Religious Fervor and a Native Talent for Plastic Expression. The photos presented here are actually details from the outermost Panel 1, which presented the indigenous people of Mexico before the Spanish invasion.

Panel 1 of Rivera’s mural shows Olmec, Maya, Toltec, Mixtec, Yaqui, and Aztec people involved in activities throughout the ages that range from religious ritual to holding high council. The emphasis however is upon indigenous artisans and their craft production. In the above close-up detail, Rivera depicted a Toltec craftsman using a primitive hand-drill powered by a bow to cut a stone statue, part of a group of Toltec artisans sculpting stone statuary. Rivera based the features of the man’s portrait upon the stylized way in which the Toltec people portrayed themselves. The Toltec flourished in central Mexico from around 1200 BC to 400 BC. The Aztecs considered the Toltecs to be their forerunners, and regarded them as the very embodiment of a refined culture; in fact in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs, Tōltēcah meant “artisan.”

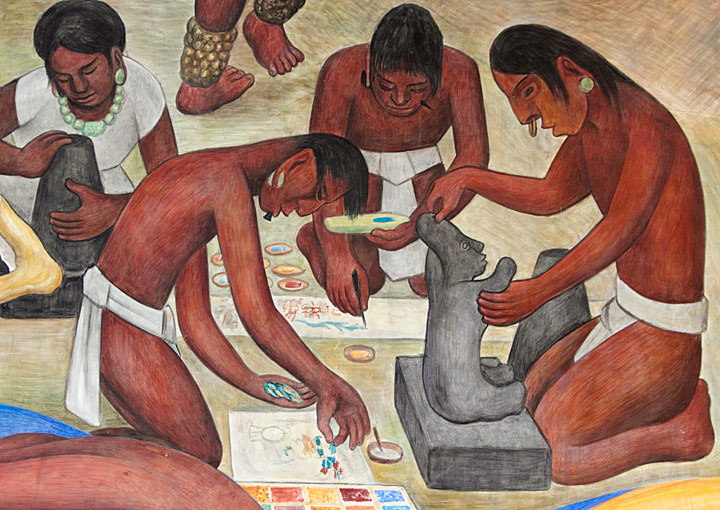

In Panel 1 Rivera also painted the above grouping of Olmec artisans at work. The woman at top left is fashioning a ceramic vase, at foreground left a man is designing a mosaic of turquoise and shell, at center another is painting a pictographic scroll, while the man at right is creating a statue of a male figure. The Olmec were the first great civilization of Mexico (2000 BC – 400 BC), though less is known about them compared to more recent cultures like the Maya and Toltec. For example, we do not even know how they referred to themselves; the Aztecs called them “Olmecatl,” which in Nahuatl was the equivalent of “rubber people,” since the Olmec were the first to extract latex from rubber trees, using it for practical, religious, and artistic purposes. The Olmec are perhaps best known for having created colossal human heads sculpted from basalt boulders, but overall their sculptures in basalt, jadeite, greenstone, serpentine, granite, and wood are superlative, and provide much of what we do know about the “rubber people.”

In the extreme close-up detail from Panel 1 shown below, Rivera painted a portrait of the Aztec Emperor, Nezahualcoyotl (1402-1472), whose name meant “Hungry Coyote” in the Nahuatl language. While he was the ruler of the mighty Aztec Empire, a realm that encompassed all of central Mexico between the Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico, Nezahualcoyotl was originally the King of Texcoco. That impressive megalopolis was located on the north shore of Lake Texcoco, and was part of the tri-city-state alliance of Tenochtitlán, Texcoco, and Tlacopan that actually comprised the empire. Ultimately Tenochtitlán became the most powerful city and the nucleus of the empire, but Nezahualcoyotl remained attached to his native Texcoco, which he transformed into a wellspring for Aztec art and culture.

Known as the “philosopher king,” Nezahualcoyotl was also a celebrated architect, engineer, and city planner. He designed a dike that separated the fresh and brackish waters of Lake Texcoco, a system vital to the floating city of Tenochtitlán, which would come to have a population of some 300,000 inhabitants. He also implemented a massive aqueduct system to bring fresh water into the city-state of Texcoco. Nezahualcoyotl established cultural institutions; an academy of music, a zoological garden and arboretum, a vast library of pictographic books (later destroyed by the invading Spanish conquistadors). He also created a sophisticated code of laws that strictly governed civic and public life. But Hungry Coyote is perhaps best remembered for his poetry, which continued to profoundly move people generations after his death.

Rivera’s portrait of Nezahualcoyotl is pure conjecture, since accurate depictions of the emperor were not made during his reign. He was certainly portrayed by Aztec artists, but only in highly stylized ways. Likewise, he was illustrated in pictographs, but in the blunt, rather non-descript portrait style of Aztec artisans. All the same, Rivera painted the Aztec ruler in Kingly attire, resplendent with a crown of gold, a golden nose-plug and earrings, and a royal cape made of bird feathers and held in place by a golden cloak clasp inset with turquoise and sea shell.