“It feels as if art is failing us”

50 years ago on February 21, 1965, Malcolm X was assassinated at the Audubon Ballroom in Manhattan, New York. This short essay is a reflection on Black History Month and how the explosive social events of the 1960s helped to shape my life and viewpoint as an artist. By extension, it is also a rumination on how artists must react to the issues of race and class facing America today.

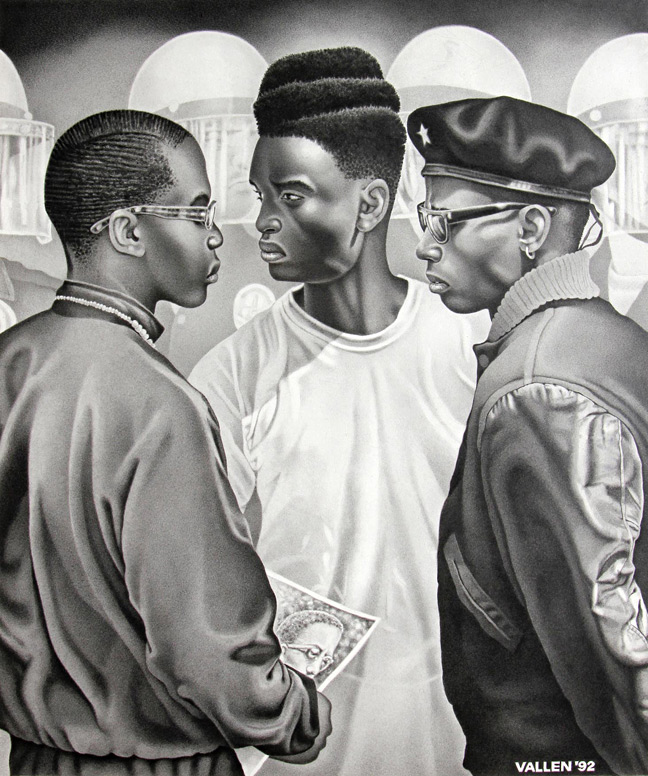

In the wake of four Los Angeles Police Department officers being acquitted for mercilessly beating, clubbing and kicking Rodney King after a high-speed car chase, I created the drawing No Justice, No Peace in the immediate aftermath of the riots that engulfed Los Angeles on April 29, 1992. One of the three young protesters I depicted in my drawing holds a flyer emblazoned with a photo of Malcolm X. I published my drawing as an edition of 5,000 offset litho flyers that were distributed all across the city; the leaflets bore the stencil letter headline of… No Justice, No Peace. It would not be the first time that I created an artwork that examined race in America; I had been making such images since I was a rebellious high school student in 1968.

I was only six-years old in 1960 when I saw newspaper photos of white racist thugs beating up African-Americans who dared to sit at segregated lunch counters in the South. A year later at seven-years old I saw news photos of racist white mobs beating Freedom Riders and burning their buses in Alabama. As a nine-year old in 1963, I watched television broadcasts of African-Americans marching for their human rights on the streets of Birmingham, Alabama, and was horrified to see them savagely assaulted by policemen, set upon by snarling police dogs, and attacked by cops using high-pressure water hoses for “crowd dispersal.”

There was so much more: the ’63 dynamite bombing of the African-American 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama that took the lives of four little girls; the ’64 police kidnapping and KKK murder of three civil rights workers in Mississippi; the assassination of Malcolm X on Feb. 21, 1965; the Orangeburg massacre of Feb. ’68, where hundreds of black students protesting racial segregation in Orangeburg, South Carolina were fired upon by police with carbines and shotguns, killing three young men and wounding 28 (predating the 1970 Kent State killings). Then, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968. I remember all of those events and so much more, just as if it all happened yesterday.

It is remarkable to think that in the suburban neighborhood in Los Angeles where I grew up as a teenager, I walked every Friday to a local newsstand, a hub in the community, and purchased the weekly edition of The Black Panther Intercommunal News Service, the party’s self-published newspaper. It is also striking to consider that I submitted a political cartoon to the Panther publication, sometime around 1969 or 1970 (the date escapes me). I received a letter from the Panthers that they had published my cartoon! That cartoon would be my very first published artwork; but that is a story for another time.

But concurrent with my political baptism came an aesthetic, cultural awakening. My interest in the Black liberation movement also led me to discover a plethora of African-American artists; giants like Jacob Lawrence, Romare Bearden, John Biggers, Charles White, Betye Saar and many others. I have learned from and been inspired by many art movements: the Mexican Muralists, the German Expressionists, the American Social Realists of the late 1930s, but I would not be the artist I am today had it not been for the Black Arts Movement.

As a teenager in the 1960s, I cut my teeth on the social struggles just described, and with my understanding of art and cultural work as a necessary component to social change, I began to make art that confronted war, racism, imperialism, police brutality – the exact same problems that continue to plague us today. As a young artist in the 60’s, these themes filled my sketchbooks.

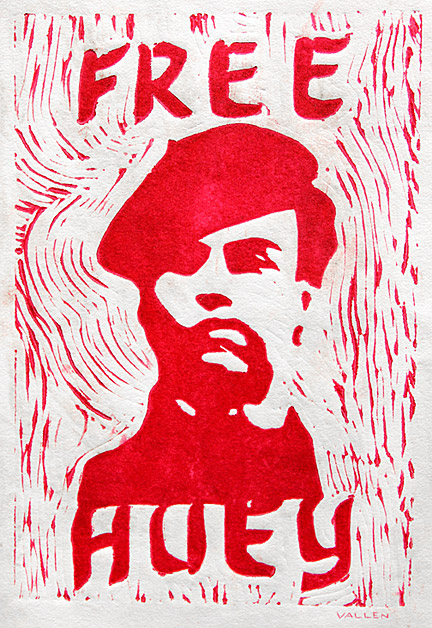

As a fourteen-year old in 1968, I created my first clumsy attempt at a linoleum cut.

The print was inspired by the “Free Huey” campaign the Black Panther Party was then waging on behalf of its jailed Minister of Defense, Huey P. Newton. The drive to free the Panther leader became a cause célèbre in the U.S., especially for young Blacks fed up with racial oppression.

I remember making black and white copies of my linoleum print on a Xerox Machine, a new technology at the time, and posting the facsimiles in my neighborhood. It would be my first foray into hit and run public art.

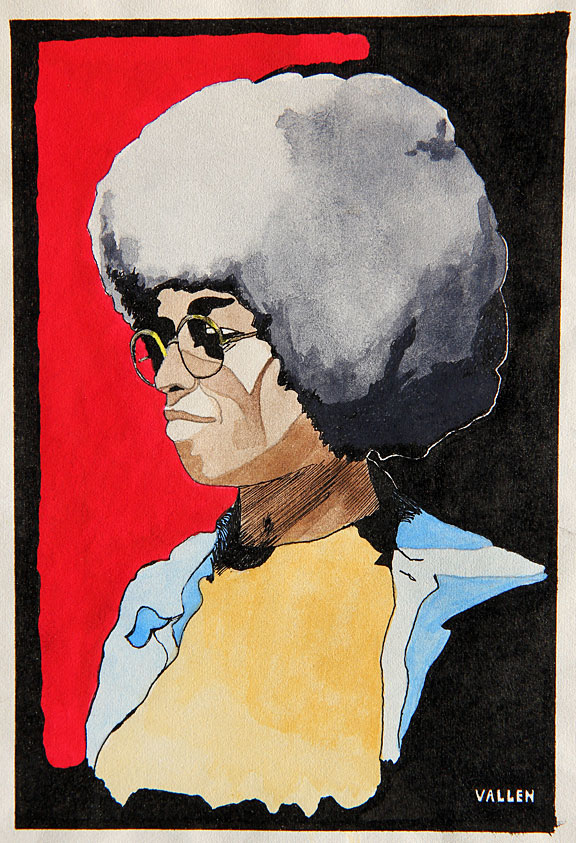

In 1970 I created a small drawing of Angela Davis after she had been arrested on trumped-up charges of murder. While Davis was never a Panther, she was an ardent supporter. It should be remembered that on Dec. 4, 1969, Fred Hampton and Mark Clark of the Black Panther Party chapter in Chicago, Illinois were murdered by the police in a raid on Hampton’s apartment… bringing the number of Panthers killed by the police up to that point to 28.

There were plenty of other non-Panther African-American activists that fell victim to state repression at the time, so the fear that Davis might join them was a realistic one. While I never published my ink and watercolor portrait of Davis, I was very much involved in the international “Free Angela” movement that demanded her freedom.

I am sharing these memories to make a point, that a humanist art that resists and scorns injustice must come from real world experience. Such art grows out of an understanding of history and a great love for common people; more importantly, it springs from communities of people yearning and struggling for a better life. Because of my deep involvement with the civil and human rights movement of African-Americans, I cannot view art in any other way.

The debate regarding the social role of art in America remains as burning a question as it ever was. The protests and riots in Ferguson, Missouri over the police killing of Michael Brown; the heinous strangulation death of Eric Garner at the hands of the New York Police Department and the crushing pathos of the attendant “I Can’t Breathe!” rallying cry; the mass demonstrations of the Black Lives Matter movement, all give the lie to the nonsense about a “post-racial” society having been ushered in by President Obama.

But where is the art that gives voice to these concerns? Why the full-blown torpor and inattention from the artistic community? It has much to do with the postmodern art quackery that prefers kitsch, detachment, irony, and simulacrum to hard facts and universal truths. Figurative realism and meaningful narrative, let alone heartfelt humanistic concerns, have been considered passé by art world gatekeepers for decades. Combine that toxic mix with art star celebrity worship and the near total commodification of art, and the reasons for art world apathy and unmindfulness becomes crystal clear. It should be recalled that figurative social realism was a vibrant, if not dominant school of art in the U.S. for much of the 20th century, until it was buried by abstract art in the post-WWII period. Still, there are glimmers of hope.

On Nov. 27, 2014, the chief film critic for the New York Times, A.O. Scott, wrote an essay that broached the question, Is Our Art Equal to the Challenges of Our Times? He stated emphatically that “we are in the midst of hard times now, and it feels as if art is failing us.” Scott pointed out that in decades past, “all the news you need about class divisions” could be found in painting, theater, movies, and literature. Here he explicitly wrote that he was “waiting for The Grapes of Wrath. Or maybe A Raisin in the Sun, or Death of a Salesman, a Zola novel or a Woody Guthrie ballad – something that would sum up the injustices and worries of the times.” Mr. Scott will be waiting for a long time… all we get is 50 Shades of Grey, Justin Bieber, and some ludicrous balloon dogs from the vacuous Jeff Koons. While Scott offered no answers to the crisis in art, he did ask some of the right questions. His disquiet regarding how things stand in the arts are a starting point for serious discussions on the future of art.

One thing is certain, now is the time for artists the caliber of Langston Hughes and Elizabeth Catlett to appear on the scene. It is also undeniable that the “culture industry” of 21st century America, so invested in spectacle and distraction, will not present critical artists to the public at large. But what can also be stated with certitude is that such artists will come from the people.