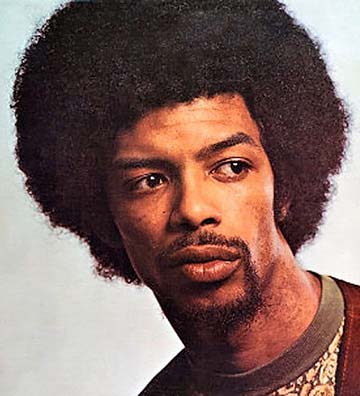

In Praise of Gil Scott Heron

Gil Scott Heron died on May 27, 2011 at the age of 62. Some obituaries have referred to him as “The Founding Father of Rap”, but as the BBC put it in their coverage of Heron’s passing, “He was quick to reject some of the more grandiose epithets such as the ‘Godfather of rap.'” I think it proper to refer to Heron as a griot. In the traditions of West Africa, a griot is an itinerant musician and storyteller who keeps alive a people’s history through song and poetry. That was certainly Heron’s role in life, and his works had an enormous influence on my generation.

In explaining his artistry, he once said; “For the longest kind of a time, I have felt that people who said that they did not care anything about politics or were not interested in it were making a political statement in and of itself. The new poetry that evolved in our society, concerned the fact that folks wanted to use both words that people could understand, and well as talk about ideas that people could understand.” I shared Heron’s belief that art, in no small sense, sprang from an awareness of the world, and his music was the iconic soundtrack for my life as a politically engaged artist throughout the 1970’s and beyond.

I first heard Gil Scott Heron in 1970, when he released his debut album, A New Black Poet: Small Talk at 125th and Lenox, a searing piece of vinyl that castigated American consumerism, racism, and pseudo revolutionaries. The album contained Whitey on the moon, a poem set to music that brought attention to the contradictions of spending vast amounts of money on the space race while social and racial inequality festered in America’s urban slums. But the album’s real gem was The Revolution Will Not Be Televised, a raging spoken word piece set to conga drums that damned America’s commercial media and advertising empires and the somnolent effect they have over a confused population…

“The revolution will not be right back after a message

about a white tornado, white lightning, or white people.

You will not have to worry about a dove in your

bedroom, a tiger in your tank, or the giant in your toilet bowl.

The revolution will not go better with Coke.

The revolution will not fight the germs that may cause bad breath.

The revolution will put you in the driver’s seat.

The revolution will not be televised, will not be televised,

will not be televised, will not be televised.

The revolution will be no re-run brothers;

The revolution will be live.”

The Revolution Will Not Be Televised became anthemic in a way, its truth immediately grasped by all those who imagined a different type of society, this is still true today. The song’s title has entered the English lexicon, defining the chasm between real social events and the fallacious spectacles broadcast by capitalist mass communications. As Heron himself put it in an 1990s era interview;

“The first change that takes place is in your mind, you have to change your mind before you can change the way you live and the way you move. So when we said that the revolution will not be televised, we were saying that the thing that’s going to change people is something that no one will ever be able to capture on film, it will be something that you see and all of a sudden you realize – ‘I’m on the wrong page’, or ‘I’m on the right page but I’m on the wrong note, and I’ve got to get in sync with everyone else to understand what’s happening in this country.'”

After his 1970 debut album I enthusiastically followed Heron’s artist output, which matured dramatically. But it was his 1975 album, First Minute of a New Day, that really got my attention. The jazz and blues oriented masterwork was a collaboration with longtime musical associate Brian Jackson. It heralded the African Liberation struggle then blazing in our collective consciousness with an infusion of African rhythms and instruments held in a jazz and blues structure. The record included the song Winter In America.

Winter In America was a devastatingly melancholy ode to the true condition of the United States. The song addressed the entropy many were sensing at the time; Nixon’s Watergate debacle was in the news but there was no resolution, America’s war on Vietnam was being lost and would totally collapse in ’75; the powerful Black Liberation, student, and antiwar movements were dwindling. “And I see the robins perched in barren treetops, watching last-ditch racists marching across the floor, but just like the peace sign that vanished in our dreams, never had a chance to grow.” Oddly enough, Heron’s elegy seems all too relevant to our current situation.

First Minute of a New Day also contained the evocative Guerilla, and We Beg Your Pardon America, a scathing indictment that lambasted the pardoning of Nixon by Gerald R. Ford – the only U.S. president recognized by official circles not to have been elected. For many of us, the righteousness expressed in Heron’s spoken word piece would be the only semblance of justice to come out of the Watergate fiasco. The album also contained the song, Ain’t No Such Thing as Superman, a still relevant warning to those who believe that a political superhero will come to our rescue.

If First Minute of a New Day put us in touch with the African Liberation Movement, then the 1976 From South Africa To South Carolina spurred us all into action. The album contained Johannesburg, a call to actively support the freedom fighters then battling the vile racist South African apartheid regime. “Well I hate it when the blood starts flowin’, but I’m glad to see resistance growin’.” Listening to that song for the first time I knew I would become actively involved in the anti-apartheid movement; some years later when distributing my Free South Africa poster at demonstrations against apartheid rule, protestors chanted a refrain from Heron’s song; “What’s the word – Johannesburg!” (a video of Heron’s live performance of Johannesburg can be viewed on the BBC’s website).

There are many other brilliant musical diatribes from Heron that are etched upon my mind, his caustic Jose Campos Torres (1979), the anti-nuclear Shut Em Down (1980), the anti-Reagan Re-Ron (1983). Heron’s discography is much too extensive to list here, and I have not even mentioned his most recent recordings; those unfamiliar with his output are urged to take a closer look. His best works will no doubt become eternal, and it is difficult to imagine that there will ever be another Gil Scott Heron – yet times demand that other singer/songwriters step forward to play the role of griot.