¡ADELANTE! Mexican American Artists: 1960s and Beyond

I will be premiering two new oil paintings at ¡ADELANTE! Mexican American Artists: 1960s and Beyond, the latest museum exhibition to explore the world of Chicano art. Presented by the Forest Lawn Museum in Glendale, California, the exhibit runs from September 9, 2011 through January 1, 2012, and offers the paintings, drawings, prints, sculptures, and photographs of some forty artists. Included are artworks from “veteranos” of the 1960s Chicano Arts Movement, as well as from a whole new generation of artists involved in creating Chicanarte (Chicano art).

Those influential artists participating in the exhibit include the likes of Judith F. Baca; David Rivas Botello; Barbara Carrasco; Margaret García; Ignacio Gomez; Wayne Healy; Leo Limón; Frank Romero; Patssi Valdez, and a host of others. A few of the works on view are from the Cheech Marin Collection, one of the most important private collections of Chicano art in the United States. Adelante is Spanish for “advance” or “forward”, making the perfect title for an exhibit that surveys Chicano art as it moves into the second decade of the 21st century.

When Joan Adan, curator and exhibit designer for the Forest Lawn Museum, requested my participation in the Adelante show, I made a commitment to create a pair of new oil paintings especially for the occasion. I would have barely four months to complete the works. I had been conceptualizing a number of large canvasses based upon observed life in the city of Los Angeles, so when Ms. Adan offered inclusion in Adelante – my ideas became concrete. I was determined to paint narratives that typically get little attention in Chicanarte exhibits. I chose to create paintings inspired by a major event in Mexican-American history, the National Chicano Moratorium Against the Vietnam War, telling the story of how that event continues to resonate in the present.

The Chicano Moratorium march took place in East Los Angeles on August 29, 1970, and was partly organized by the Brown Berets, a militant Chicano group that fought for the civil and human rights of Mexican-Americans. The Brown Berets were originally organized in East L.A. in 1967 as an outgrowth of the burgeoning Chicano civil rights movement. In 1968 the group organized the first student walkouts to protest racism and substandard schools in East L.A., electrifying an entire generation. Soon Brown Beret chapters sprang up throughout California, Arizona, Texas, Colorado, New Mexico, and beyond – but it all started in the city of Los Angeles.

Some 30,000 people took part in the 1970 moratorium march, which culminated in a rally at Laguna Park; dozens of Brown Berets acted as marshals, providing security for the protest. The L.A. County Sheriff’s Department attacked the gathering, initiating a riot. Ultimately police killed four citizens that day, Lyn Ward, José Diaz (both Brown Berets), Gustav Montag, and L.A. Times reporter Rubén Salazar. Salazar was slain as he sat in the Silver Dollar Café; a deputy sheriff fired a tear gas projectile into the cafe, striking Salazar in the head and killing him instantly.

To commemorate the 40th anniversary of the Chicano Moratorium, on August 27, 2010 I joined 5,000 others in walking the original march route along Whittier Blvd. Instead of the Vietnam War, we protested the current U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. A new generation of Brown Berets provided security for the march – as well as inspiration for my painting, La Causa. The Brown Berets disbanded in 1972, but were re-activated in 1993 under the group’s original charter and mission statement; the organization currently seems to be flourishing. As the multitudes passed where the Silver Dollar Café once stood, piles of flowers were placed on the spot where Rubén Salazar was killed. We rallied at Rubén Salazar Park (formerly known as Laguna Park), where forty-years ago the police provoked the riot now recorded by history.

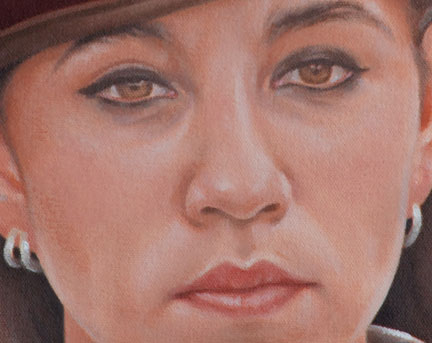

My oil painting, La Causa (The Cause), is a depiction of two of the female Brown Beret cadre I caught a glimpse of at the 40th anniversary protest march. The title of my canvas is taken from the words that appear on the emblematic patch worn on the berets of the organization’s members, the “cause” being the liberation of the people.

I felt it important to portray these young Chicana activists as a counter-balance to the stereotypical images of Latinas. Despite their legendary public image, at least as it is known in the greater South West of the U.S., I think mine might be the first serious painting of Brown Beret members. My canvas is not a wholesale endorsement of the group’s cultural nationalist political philosophy, but rather an acknowledgement of the role the organization has played in the history and collective consciousness of Mexican-Americans.

It is ironic that while working on my La Causa painting, I received word that the FBI and the SWAT Team of the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department raided the home of Carlos Montes on May 17, 2011. Montes, a co-founder of the Brown Berets and a leader of the historic student walkouts in East L.A., had his cell phones, computer, notes, and other personal affects seized by the authorities. Apparently the Obama administration has targeted Montes for his antiwar activities, part of an underreported repressive sweep the Obama Justice Department has initiated against antiwar activists as reported in the Washington Post. As of this writing, the government’s case against Carlos Montes is still pending.

What initially attracted me to the Chicano Arts Movement in the early 1970s was its innovative merging of aesthetics and political concerns; it was a populist, anti-elitist school of art that sprang from a people’s struggle for equality, democratic rights, and self-determination. Chicanarte took inspiration from the Mexican Muralist School of social activist art, but it succeeded in creating its own unique visual language that reflected the distinctive Mexican-American experience. While the elite art world discarded painting altogether in favor of postmodern conceptualism and its rejection of “grand narratives”, Chicanarte never abandoned figurative realism in paintings, drawings, prints, or sculpture; a fact that largely remains so today.

Chicano artists continue to address the dreams, aspirations, history, and lived experience of la gente (the people), which is the genre’s one consistent and unbreakable grand narrative. The Chicano Arts Movement has certainly expanded since the early 1970s, nowadays incorporating performance, installation, abstraction, and other disciplines, but for the most part it still retains the activist spark of its founding years. The state of U.S. society today, with its austerity budgets, numerous wars, economic decay, and xenophobic anti-immigrant stance, gives impetus for the social realist activist component of Chicanarte to once again move front and center.

¡ADELANTE! runs from September 9, 2011 through January 1, 2012. The Forest Lawn Museum is located at Forest Lawn Memorial Park, 1712 South Glendale Avenue, Glendale, California. 91205. The museum is open every day except Monday, from 10 am to 5 pm. Admission and parking is free. Phone: 1-800-204-3131. Website: www.forestlawn.com. A larger reproduction of La Causa can be viewed here.