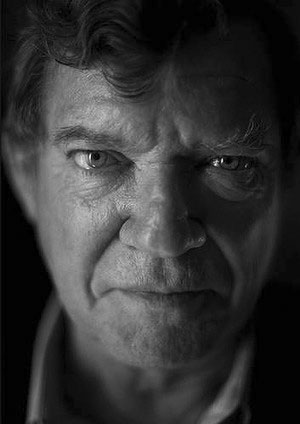

Robert Hughes: the last art critic

“Some think that so much of today’s art mirrors and thus criticizes decadence, not so – it’s just decadent, full stop. It has no critical function, it is part of the problem. The art world beautifully copies our money driven, celebrity obsessed, entertainment culture; same fixation on fame, same obedience to mass media that jostles for our attention with its noise and wow and flutter.” – Robert Hughes.

Robert Hughes died on August 6, 2012, at the age of 74. He passed away at a hospital in New York following a long unspecified illness. There are more than a few obituaries written for Mr. Hughes… you can ignore them all. Let Hughes’ sharp-witted writings and proclamations be his obituary; his lacerating words are enough to understand why he is still an indispensable force in today’s money besotted art world.

The quote that opens this remembrance of Mr. Hughes came from his 2008 documentary film for Britain’s Channel 4 television, The Mona Lisa Curse. The film explored, in the words of Hughes, how “the entanglement of big money with art has become a curse on how art is made, controlled, and above all – in the way that it’s experienced.”

The great majority of obituaries for Hughes rightfully mention his 1980 book and TV series, The Shock of the New, or his 1997 book and TV series American Visions, conversely, few if any mention his last major documentary, The Mona Lisa Curse. While many commentators laud Hughes for the vital contributions he made to the public’s understanding of art, they fall silent when it comes to The Mona Lisa Curse, a work that so upset the postmodern apple cart that it has been cast into oblivion.

Soon after its Sept. 18, 2008 broadcast on British TV, I found that The Mona Lisa Curse had received virtually no attention in the United States; the blackout affected the mainstream press (New York Times, Los Angeles Times, etc.), the art press, and the blogosphere. Mercifully, someone posted the entire documentary in twelve parts to YouTube in November of 2009, whereupon I immediately wrote a web log post about the documentary. My post provided a link to each of the twelve streaming video segments on YouTube, gave a summation of each part, and included pull quotes from Mr. Hughes.

Since my post was apparently the only article in existence that directly linked to The Mona Lisa Curse video on YouTube, I would like to think that thousands were exposed to Hughes’ masterwork due to my efforts.

As of this writing the U.S. press remains mute when it comes to The Mona Lisa Curse. The film is unavailable on Amazon.com and Netflix.com because it has not been released as a DVD by its producer C4/Oxford Film & Television. The company has provided no information on when the documentary might see the light of day. For all practical purposes Hughes’ most profound and deeply pertinent work continues to be unheard of; his polemics certainly did not win him any favors, but then, they were not meant to – his aim was to banish a curse.

In The Shock of the New TV series Hughes spoke of modern architecture and how its visual language serves the needs of state power; it was an analysis that foreshadowed the formidable critique to come later in The Mona Lisa Curse. Hughes’ survey included critical observations regarding the imperial architectural designs of fascist Italy and Germany from the 1930s, an aesthetic he recognized in the style of corporate architecture found in the 1980s. The concluding words of my short eulogy to Robert Hughes were uttered by the great man himself during his televised Shock of the New exposition on architecture:

“As far as today’s politics is concerned art aspires to the condition of muzak, it provides the background hum for power. If the Third Reich had lasted until today the young bloods in the party wouldn’t be interested in old fogies like Albert Speer or Arno Breker, they’d be queuing up to have their portraits done by Andy Warhol. It’s hard to think of any work of art of which one could say, ‘This made men more just to one another’, or ‘This saved the life of one Jew or one Vietnamese.’ Books perhaps, but as far as I know… no paintings or sculptures. The difference between us and the artists in the 20s, is that they thought that such a work of art could be made. Perhaps it was their naïveté that they could think so – but it’s our loss that we can’t.”