Roberto Chavez & The False University

Roberto Chavez and The False University: A Retrospective, is a noteworthy exhibition of works by the 82-year old Chavez, an artist that should be a better known figure from the school of Chicanarte (Chicano art). The Vincent Price Art Museum at East Los Angeles College (ELAC) offers an exhibit comprised of more than 50 artworks by Chavez that cover a surprisingly wide range of mediums and styles.

While the works of Chavez are grounded in the Mexican-American experience, they are universal in scope. A number of his early canvases are playfully cubist, and expressionism is a current that runs through his art. When viewing some of the artist’s paintings, I was reminded of the works of Arshile Gorky, especially his famous canvas The Artist and His Mother. That trace of Gorky’s influence is evident in The Group Shoe, a 1962 oil on canvas by Chavez. I could also see Van Gogh’s 1885 painting The Potato Eaters in works by Chavez, not because of theme or even technique, but for reasons of temperament. Chavez’s The Artist’s Brother, Raul (1959) displays hints of Van Gogh’s 1885 canvas.

But Chavez is not a Gorky, Van Gogh, or Picasso, he is uniquely himself. That fact aside, there are nonetheless inconsistencies and weaknesses to be found in his work. Some paintings like his 1980 Birth of Genji are so unappealing, in an obnoxiously aggressive expressionist manner, that one winces and quickly moves on. In a few of his lesser works, the artist seemed to be struggling with aesthetics and narrative, as if unsure of what to say or how to say it.

The retrospective for Chavez presents the first museum examination of his censored mural, The Path to Knowledge and the False University, painted on the facade of a building at East Los Angeles College in 1974. Created at the zenith of the Chicano movement, the mural pointedly criticized the curriculum of the college as irrelevant to Chicano students, hence the title of “False University.” The college administration perceived the mural as a threat, and whitewashed it in 1979. It is amazing how such a non-threatening painting could ruffle so many feathers.

But on the other hand, frankly speaking, despite the attention given to the mural in the exhibit, it is fairly shaky artistically and feeble as a political work. Its importance comes from being censored and having served as a lightning rod for an angry community, rather than any inherent artistic weight. That being said, it is a long overdue and welcome move that ELAC would admit to, and present for research and discussion, their 1979 act of censorship.

Despite the chinks in Chavez’s armor, his weak points and failings, his oeuvre is otherwise sterling. He is a genuine painter’s painter. Overall, though the works of Chavez in the retrospective are not necessarily didactic, curious viewers will discover a sense of history in them; those who dig deep may unearth certain truths about the world. In that sense Chavez continues to carry the banner of Chicanarte, which up to the present still largely upholds figurative realism, narrative, craft, and an exploration of the human condition, as foundational and necessary facets of art. Being a champion of such an aesthetic is perhaps Chavez’s greatest triumph.

The balance of this non-review will present my thoughts on a number of paintings from the retrospective that I thought impressive. Owing to the generosity of the Vincent Price Art Museum, I was allowed to take some close-up photographs of the artist’s works, those photos will illustrate my reflections on the art of Roberto Chavez.

A student and assistant of Roberto Chavez beginning in 1965, Gilbert “Magú” Luján (1940-2011) went on to become a leading artist and theoretician in the Los Angeles based Chicano art movement. Magú worked on a commission he had received in 1990, to incorporate art into the Hollywood and Vine station on the Metro Rail Red Line of Los Angeles, California. The Metro Station project consisted of a series of images depicting anthropomorphized animals and pre-Columbian figures driving around Hollywood in lowrider cars; Magú had drawn the images by hand onto dozens of ceramic tiles that were set into the walls of the Metro station. That and his fanciful sculptural benches shaped into lowrider cars, transformed the Hollywood and Vine station into a miniature Magulandia. Magú completed the Metro station project in 1999.

I met Magú around 2003, and we remained friends and artistic compañeros until his passing.

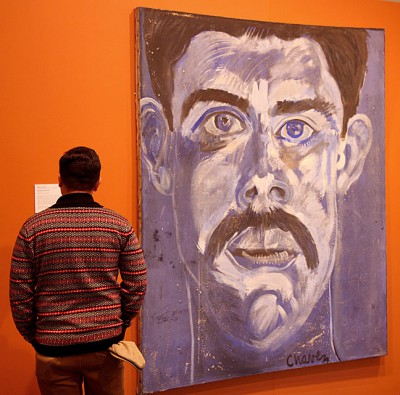

Once again leaping over the boundaries of Chicano art, the Chavez portrait of Magú looks as if it could have been painted by Karl Schmidt-Rottluff or Conrad Felixmüller, two German Expressionist artists from the 1930s that I greatly admire.

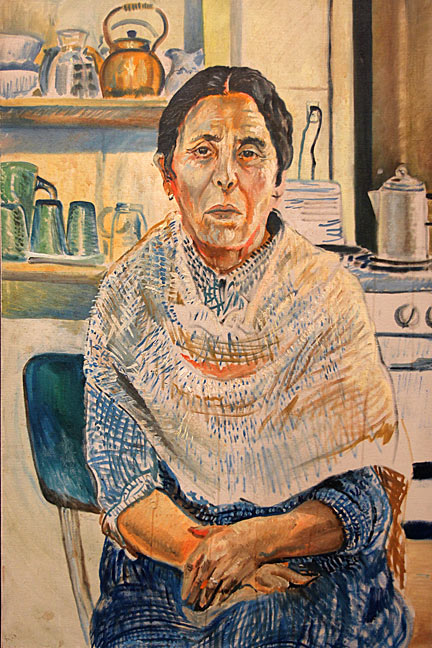

The Artist’s Mother illustrates a scene familiar to most older Mexican-Americans, the matriarch of a family surveying the world from her kitchen domain. This could be a portrait of my deceased grandmother, Dolores Maytorena-Riveroll, who lived in a small wooden house in the barrio of San Diego, California.

With this painting Chavez took the ordinary and made it sublime, he took what was familiar to millions, and made it iconic.

My grandmother came to the US in the late 1920s as a young woman from Guaymas, Mexico, and ended up living in San Diego where she worked in the city’s Chicken of the Sea canning factory.

I came to know her when I was a child; she was old and deeply wrinkled, but full of life. A devout Catholic, she wore conservative dresses and shawls, and kept her hair in a bun. In my mind, she was the finest cook I have ever known, and from her tiny kitchen came Mexican culinary delights that seemed to come from paradise. I can still hear the sound of her patting tortilla dough between her hands as she made tortillas de harina.

I am sure Chavez had similar memories of his mother… the kitchen painted in the background of The Artist’s Mother looks exactly like the one belonging to my grandmother, from the glassware to the inexpensive chrome and vinyl kitchen chair.

The painting is beautifully if roughly executed. Starting with an underpainting done in cadmium orange, the portrait is built up in layers of blues and browns. The flesh tones are transparent, allowing the bright orange to peek through. The shawl and loose fitting dress are brilliantly painted with a mass of squiggly, nervous brushstrokes… some barely registering, others deftly laying down pigment from a fully loaded brush.

In the vibrant oil painting, Japanese Fish Kite Chavez created a still-life from Japanese craft items.

At first glance the painting could be mistaken as a work from the 1930s school of German Expressionism, but that is one of the things I appreciate about it, the artwork transcends the narrow definitions of Chicano art. Prominent in the composition is a red “fish kite” (hence the name of the painting), but below it, painted in almost mirror-like fashion, is another fish kite colored dark green.

At the lower left of the canvas can be seen a swath of the traditional indigo dyed fabric known as shibori; Japanese ceramic and porcelain bowls surround the kites. In actuality koinobori, carp-shaped “wind socks,” are flown in Japan during the month of May to celebrate the ancient tradition of Boy’s Day – tango no sekku. The carp is highly regarded in Japanese folklore as a determined and strong fish that battles upstream and fights to overcome adversity, hence it became an iconic symbol for Japanese families honoring their sons.

In 1948 the post-war Japanese government declared that the May 5th Boy’s Day celebration would be combined with the traditional March 3rd Girl’s Day celebration – hinamatsuri (literally, Doll Festival), to become Children’s Day – kodomo no hi. The new national holiday celebrating the “happiness of all children,” was to be celebrated on May 5th, with the brightly colored koinobori as its symbol. I became familiar with these traditions during my life-long association with the Japanese community of Los Angeles, located in the historic “Little Tokyo” area of downtown L.A.; In 1987 I maintained an art studio in an old 1911 brick warehouse in the Little Tokyo district, walking distance from the Buddhist Higashi Hongwanji Temple. My understanding of and appreciation for Japanese culture and aesthetics has had no small influence on my life as an artist, and a number of my paintings reflect this.

A surprising number of paintings by Chavez in False University, show the influence of Japanese culture and aesthetics. Aside from Japanese Fish Kite, other paintings also featured Japanese motifs. His large oil on canvas, North Coast Venus (not shown here), is somewhat reminiscent of a Renaissance portrait, but it just as readily conjures up the aesthetics of Japan’s Ukiyo-e (floating world) prints from Japan’s Edo period. Created in 1984, the painting shows a white female nude surrounded by sea life from the northern California coast, a large starfish and octopus at her feet.

During the Second World War President Roosevelt, a Democrat, used an executive order to intern the entire Japanese American community living on the Pacific coast of the United States. Some 200,000 individuals, the great majority of which were US citizens, had their properties seized and were sent to concentration camps. Prior to the war there were many opportunities in LA for cultural engagement between Japanese Americans and those Americans of Mexican heritage – in some instances their neighborhoods literally overlapped. During the war years Little Tokyo was completely emptied of its Japanese American residents, but after the war ended in August of 1945, they started to slowly drift back into Southern California. When Chavez painted Japanese Fish Kite in 1956, Japanese Americans were beginning to regain a foothold in the region.

There is no doubt that Chavez, like myself, was directly influenced by the Japanese community of Los Angeles. In fact, the Chicano working class area of East Los Angeles where Chavez was born, was also home to a large number of Japanese Americans. I would argue that a unique hallmark of the LA school of Chicano art, is its having assimilated Japanese culture, unconsciously or not. I believe this is extant in the works of Chavez, and it is his awareness of other communities that helps to make the artist an exemplar in the Chicano art movement.

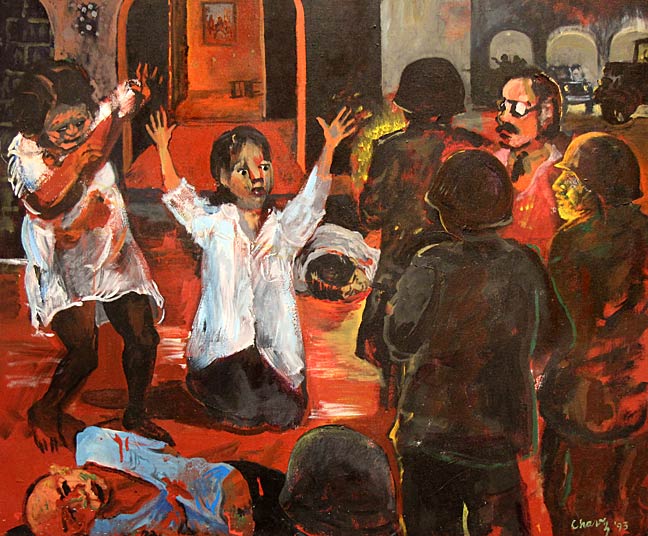

The Goyaesque painting, Incident in El Salvador, depicts the recent past of El Salvador. From 1979 to 1991, the Central American nation was torn asunder when grinding poverty and repression led to revolution and counter-revolution. Salvadoran oligarchs organized death squads to eliminate their left-wing opponents both real or perceived, in large part triggering the uprising.

One of the first death squads was the UGB – Unión Guerrera Blanca or “White Warriors Union.” The name had nothing to do with race, it was a proclamation that the UGB were patriotic anti-communists (Whites), fighting against communists (Reds). The UGB were also known as the Mano Blanca (White Hand), because they marked the homes of their victims by leaving their handprints in white paint. Photographer Susan Meiselas took a famous photo in 1980 of the Mano Blanca signature left on the door of a peasant organizer the group had murdered.

Since El Salvador had been reduced to a nightmarish charnel house during the 1980s, Incident in El Salvador could be about any number of events, big or small, that occurred during that period.

On March 24, 1980, the Archbishop of El Salvador, Óscar Romero, was murdered by a death squad for calling for an end to repression and for siding with the poor; he was gunned down while giving Mass. Romero’s funeral took place on March 30, 1980 in El Salvador’s capital; it was attended by more that 250,000 mourners. Unbelievably, the funeral Mass was attacked by death squad snipers who shot rifles from government building rooftops, killing dozens of mourners. No one ever took credit or was charged with these crimes. After the cold-blooded murder of Óscar Romero, the revolution took off in earnest. The communist oriented Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (FMLN), fought against the Salvadoran military which was allied with the country’s oligarchs – but armed, trained, and financed by the United States.

Incident in El Salvador depicts a nighttime encounter between civilians and the security forces of the Salvadoran death squad government.

Two bullet riddled men are lying in the street, while two women plead for their lives; one women seems to have been shot and is falling to the ground, the other awaits her fate. The faces of the assassins are illuminated by automatic gunfire. The entire scene is awash in blood.

Photographer Chris Steele-Perkins documented the work of the murderous death squads while on assignment for Magnum Photos in El Salvador. His photo of families visiting a morgue to find loved ones killed by death squads illustrates the depravity of the war. In one photo, the headless bodies of victims are stacked up like cordwood, their heads neatly lined up in a row. John Hoagland was another photographer that caught the savagery of death squads while on assignment in El Salvador for Newsweek in 1979. He photographed El Playon, the dump where death squads left the bodies of their victims. Hoagland’s name appeared on a list of 35 journalists marked for death that was issued by the “Anti-Communist Alliance” death squad in 1982; in 1984 he was killed while covering a clash between guerillas and the Salvadoran army – which had most likely taken the opportunity to murder him.

Naturally, all of this and more was on the mind of Roberto Chavez when he painted Incident in El Salvador. The war that occurred in that impoverished nation during the 1980s became a subject for many artists around the globe; during those years I created a number of artworks about the conflict like We’re Making a Killing in Central America and El Salvador Presente. A negotiated settlement ended the war in 1992, but the wounds of war have not yet healed. Chavez memorialized the painful memories with Incident in El Salvador, a painting which also serves as a warning against the wars of today and tomorrow.

None of this information was placed on the painting’s caption at the museum exhibit. While other works were furnished with lengthy explanatory text, the caption placed next to Incident in El Salvador was one of the shortest descriptive texts given to any work in the exhibit. It simply provided the painting’s title, medium, and date of creation. That over 75,000 Salvadorans were killed during 12 years of war, or that hundreds of thousands of Salvadorans came to Los Angeles in the 1980s to escape the bloodshed, received no attention from the exhibit’s curators. Given that the Salvadoran exile community literally changed the face of L.A., and that Chicano artists and activists played a tremendous role in opposing the war, this oversight regarding the caption was an unacceptable error in curation.

Iphigenia has been the subject of artists throughout the ages, although she is the most unlikely character to be found in Chicano art. But that is what makes the work of Roberto Chavez such a delightful surprise.

Iphigenia was a heroine from Greek Mythology. She was the daughter of Clytemnestra and King Agamemnon, the King of Mycenae that led the ancient Greeks in war against the city of Troy. Artemis, the Goddess of the hunt, prevented the warships of Agamemnon from reaching Troy because the King had insulted her. To appease the Goddess, the King had to sacrifice his daughter, Iphigenia. Agamemnon tricked his wife by telling her that their daughter was to be wed to Achilles, the bravest and most handsome warrior in the King’s army. Clytemnestra eagerly brought the young woman to the wedding, but found instead that it was a sacrificial ritual. Some versions of the myth declare that Iphigenia was killed, while others say Artemis saved Iphigenia at the last moment by placing a deer in her place. Avenging her daughter, Clytemnestra killed Agamemnon when he returned victorious from the Trojan War.

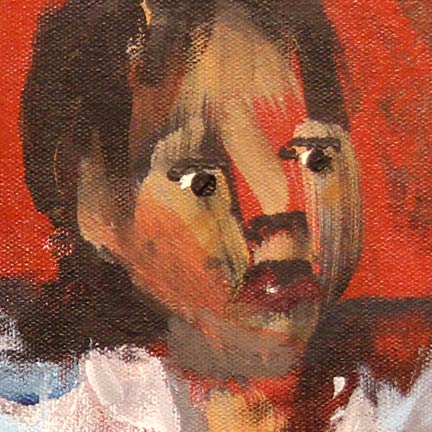

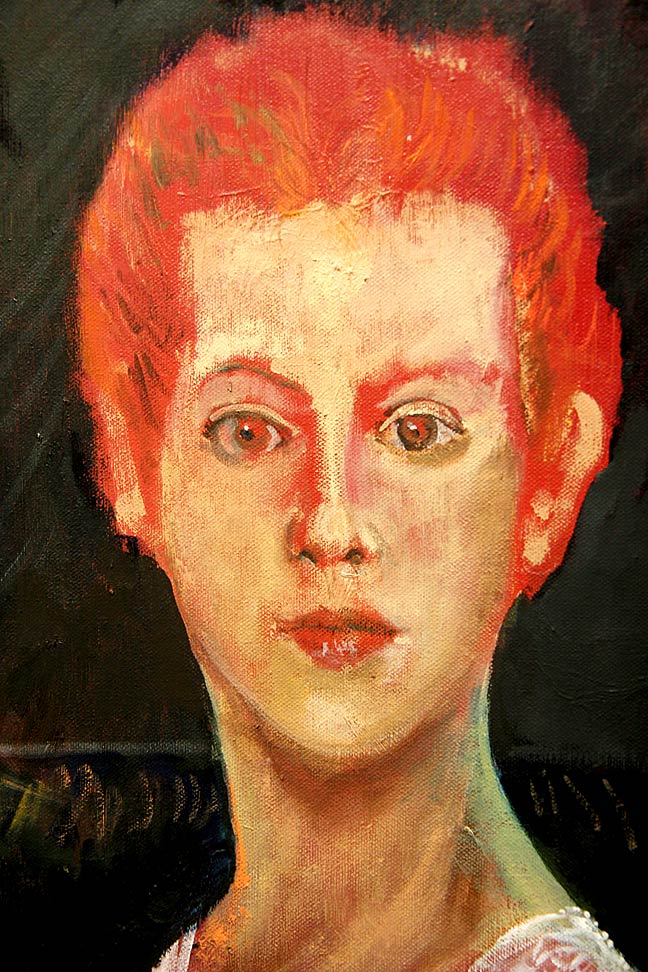

One of the most recent works by Chavez to appear in the exhibit, Iphigenia is a tour de force. Using a bright red underpainting to begin with, the artist then brushed on layers of yellow ochre and burnt sienna flesh tones while letting the underpainting peek through. The figure’s hair was achieved simply by letting the underpainting show, then brushing on a few delicate strokes of cadmium orange. An ivory black background is blocked in, giving the portrait head its final form. The subject’s eyes are accusatory and fixed on the viewer, her hair aflame with a victim’s rage. The overall look of the portrait is delicate and ephemeral.

Iphigenia is a mature work produced by a highly skilled painter. At first glance, it may seem a portrait of punk rocker Johnny Rotten executed by Eugène Delacroix, but Chavez has instead chosen to expose the viewer to Greek mythology – the legends and folklore of which have mostly been forgotten by moderns. It should be remembered, that the Greeks were the first people to give human attributes to their gods, thus bestowing these figures with continued universality and relevance. Once again, the artist pushes the boundaries of Chicano art by delving into the unfamiliar.

Golgotha refers to the site where Jesus Christ was crucified by the soldiers of the Roman Empire. The full canvas depicts piles of human skulls from victims of previous crucifixions. Amongst the rocks where the skulls sit, a white dove symbolic of the Christian Holy Spirit is shown at rest. The dove was created by troweling on white paint with a palette knife; that the background colors show through, only heightens the spiritual nature of the bird. This close-up detail from Golgotha shows how Chavez used transparent glazes and brush splatters to great effect.

It could also be said that the paintings Iphigenia and Golgotha are statements against endless war. October 2014 marked the 13th anniversary of the US invasion of Afghanistan. Just a week after the date marking the depressing event, President Obama signed a “Security and Defense Cooperation Agreement” with the Afghan government that will likely keep US Soldiers in Afghanistan for another ten years. The President has also started a new war in Syria and Iraq – without Congressional approval – purportedly to destroy the so-called Islamic State fanatics. Obama’s former Director of the Central Intelligence Agency and Secretary of Defense, Leon Panetta, said of the latest war: “I think we’re looking at kind of a 30-year war.”

One can hear the frantic protestations of Iphigenia as she is dragged to the sacrificial altar.

Roberto Chavez and The False University: A Retrospective, runs at the Vincent Price Art Museum at East Los Angeles College until December 6, 2014.