Frida in Dubai-landia

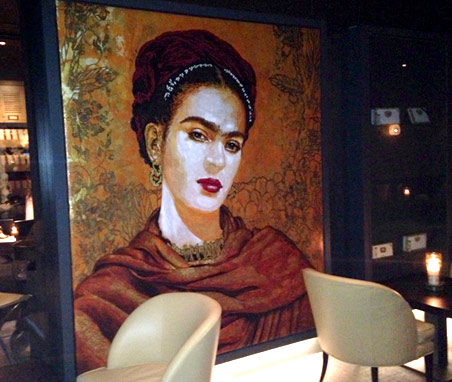

A 12 foot by 10 foot painting of artist Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) currently hangs on the wall of the IZEL “Latin American style” restaurant and nightclub at the luxurious Conrad Hilton in Dubai, United Arab Emirates (UAE).

Ironically, the painting of the Mexican communist artist was a commission IZEL gave to a Los Angeles Chicano artist (who I shall not name); it was one of eight canvases the fellow painted for the luxury hotel.

The paintings are a perfect example of the limitations and failings of contemporary Chicano art, indeed, of any art that is based upon identity politics. The paintings at IZEL represent something that I find grotesque and unacceptable, not just the commodification and “mainstreaming” of Chicano art, but the stripping away of its core values and historic importance while reducing it to the safe, decorative, and “exotic.”

Brian Bendix, the founder of IZEL and CEO of Stambac International (a global corporation that specializes in franchising, managing, and consulting high-end restaurants), said that IZEL is “where escapism is not just allowed, but is a prerequisite.” Mr. Bendix went on to say that his “Latin-inspired” nightclub will offer “the absolute best of Latin Artistry across food, cocktails, cigars and entertainment. IZEL’s launch in Dubai will be setting a precedent for the city’s vibrant nightlife scene.” Setting a precedent for nightlife in an oil Sheikh’s dream city says a great deal, especially since the megalopolis is well known for all manner of extremes.

In the words of IZEL’s owners, the nightclub presents “the ultimate, authentic Latin American experience in Dubai! IZEL oozes all the passion, style and charm that Latin America is known for.” I would say that the ostentatious establishment without a doubt oozes something, but it is most certainly not “the fire of Modern Latin America today” as claimed.

Poor Frida. When she came to the U.S. in 1930 with her husband, the famous revolutionary artist Diego Rivera, she became homesick for Mexico and complained to Diego about the materialism and soullessness of “Gringolandia,” her cutting epithet for El Norte. Now her portrait, adorned with 24 carat gold leaf like a Catholic religious icon, hangs in a restaurant frequented by oligarchs.

Kahlo’s last public act was to protest the 1954 U.S.-orchestrated military coup against the democratically elected government of Guatemala. At her public funeral in 1954 where she lay in state at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, her coffin was draped with the red flag of the Mexican Communist Party. Kahlo would be mortified to know that a ritzy nightclub in a U.S. backed oil Sheikhdom displays her portrait to provide amusement for an affluent, cigar-smoking, champagne swilling clientele. If alive today, I am sure she would contemptuously refer to the Emirate of Dubai as “Dubai-landia,” or perhaps something worse.

Founded on Dec. 2, 1971, the UAE is a federation of seven oil rich sheikhdoms located on the southeast end of the Arabian Peninsula in the Persian Gulf. Member principalities include Abu Dhabi (the largest), Dubai (the second largest), Sharjah, Ajman, Fujairah, Ras al-Khaimah, and Umm al-Quwain. Dynastic “royal” families rule the emirates, where human rights abuses, the restraint of free speech, and repression against those who call for democracy, is commonplace.

Sheikh Mohammed of Dubai (or Sheikh Mo as he is called by supporters and detractors alike), along with the other potentates of the UAE, sit upon 10% of the world’s oil wealth. According to Forbes, Mo possesses personal wealth “in excess of $4 billion,” but he has also transformed Dubai into a major financial center for global capitalism, and a leading destination for world tourism. Mo is the Vice President and Prime Minister of the UAE. The ruler of the neighboring emirate of Abu Dhabi, Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan, is President of the UAE, and according to Forbes is said to have personal wealth of “roughly $15 billion.”

Along with the painting of Kahlo, the other canvases hung in the IZEL nightclub offer sexually objectified visions of Latinas; one is a glamorous depiction of a Soldadera, those armed women who fought in the 1910 Mexican Revolution. The alluring Soldadera in the IZEL painting wears lipstick, a low-cut blouse, gold hoop earrings, a sombrero, and clutches a pair of gold-plated single-action revolvers, just like all impoverished Mexican peasant women did in 1910!

The other paintings at IZEL are clichés of beautiful “hot blooded” and “exotic” Latinas, lips parted, and striking provocative poses… but not too stimulating, as nudity and public affection is banned in Dubai, even a peck on the cheek can land one in prison for violating the Emirate’s severe “decency” laws. But the Sheikhs of Dubai are “open-minded” rulers, and they make allowances for dance-clubs and drinking copious amounts of alcohol, provided it is all done by “Non-Muslims” in a “licensed area” and the authorities get their share of the profits. Since the laws of the UAE forbid blasphemy and nudity in art, one must assume that the “oh-so-progressive” Los Angeles Chicano artist commissioned to create the paintings for IZEL, agreed not to violate the country’s strict moral guidelines. ¡Dios mío! What would Frida say?!

What bothers me so much about the paintings at IZEL, is that Chicano art once represented and spoke for the dispossessed and downtrodden. Having grown out of the Mexican American Civil Rights movement, Chicano art embraced human dignity as a main tenet. There are still faint echoes of this ethic in today’s Chicano art—but the legacy is betrayed by the paintings hanging in IZEL.

Rudi Jagersbarcher, Area President for Hilton Worldwide, said the Conrad Hilton Dubai caters “to the needs of the ever increasing number of global, affluent travelers.” Some of the affluent travelers mentioned are in reality the parasitic vultures, casino capitalists, terrorist-connected money launderers, military contractors, and foreign intelligence agents that have turned the region into a cauldron. To that mix you can add the bimbos, sycophants, and musclemen such people always have in tow, not to mention the international social set of 1 percenters that travel for pleasure. Of course the jet-setting nouveau riche of the UAE are part of the crowd; the Financial Times of London reported that in 2013 there were 54,000 millionaire Emiratis, and by 2017 that number should rise to 69,000.

It is an understatement to say that Dubai is a destination for affluent travelers. The recklessly extravagant place has outstripped Las Vegas by light-years when it comes to conspicuous consumption. Every year from January 2nd to February 2nd, the Emirate holds the Dubai Shopping Festival (DSF), an orgy of consumerism where gold, luxury cars, and diamond rings are given away to happy shoppers as promotion. The theme of this year’s DSF is “Shop At Your Best.” But Dubai also wears the mantle of political reaction reflecting the extreme conservatism of the Western-backed oil Sheikhs of the UAE.

In 1996 the American writer and social critic, Mike Davis, wrote Fear And Money In Dubai, an essay on the role Dubai and the UAE plays in global politics. Describing the bizarre architecture of Dubai as “Speer meets Disney on the shores of Araby,” Davis goes on to say that the emirates have “achieved what American reactionaries only dream of – an oasis of free enterprise without income taxes, trade unions or opposition parties.”

Davis shines a light on Dubai as “the financial hub for Islamic militant groups, especially al-Qaeda and the Taliban,” tersely noting that “Dubai is one of the few cities in the region to have entirely avoided car-bombings and attacks on Western tourists: eloquent testament, one might suppose, to the city-state’s continuing role as a money laundry and upscale hideout (….) Dubai’s burgeoning black economy is its insurance policy against the car-bombers and airplane hijackers.”

Dubai’s Dirty Little Secret was a 20/20 investigative report aired by ABC in the U.S. on Nov. 11, 2006. While the report documented the obscene wealth of Dubai’s ruling class, the “dirty little secret” reported on is Dubai’s treatment of its foreign workers, the overwhelming majority of which come from India, Pakistan, the Philippines, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka; though some 40,000 Kenyans now work in Dubai as well.

According to the 2006 ABC report, immigrant workers build the luxury hotels, shopping malls, tourist attractions, and everything else “for less than a dollar an hour.” The report revealed that more than “500,000 foreign workers live in virtual enslavement” in Dubai (that number has increased, the last official UAE count in 2010 put the number at 3.8 million foreign workers).

ABC reported that the workers are often cheated out of their pay, suffer routine abuse, and labor in dangerous working conditions. The report noted that hundreds of workers fall to their deaths each year while constructing high-rise buildings, and that “under the law in Dubai and the entire United Arab Emirates, there are no unions allowed, strikes are illegal, strikers can be fired and sent home.” I would add that immigrant workers enjoy no political rights whatsoever, and by law they are barred from ever becoming citizens of the UAE.

Dubai’s Dirty Little Secret also showed that foreign workers are made to live in squalid labor camps where they live under appalling conditions outside of the city. The report noted that sometimes up to twelve workers will live in the same room, “rooms smaller than the horse stalls in the Sheikh’s Royal Stables.” While ABC’s report did not go nearly far enough, one cannot watch it without feeling contempt for Dubai’s elites.

In April of 2008, after ABC aired Dubai’s Dirty Little Secret, some 800 Afghan, Bengali, Indian, and Pakistani workers went on strike at a high-rise construction site in Sharjah, the third largest emirate in the UAE. The strike took place because workers were being forced to sleep at the construction site as housing promised to them was never made available. The workers blockaded the streets around the site and the police were sent in; a running battle between workers and riot police ensued, with the police arresting 625 workers.

National Geographic, that bastion of subversive thought, published an article in its January 2014 edition titled, Far From Home. The article focused on Dubai’s foreign workers, particularly those from the Philippines. As with the ABC report of 2006, the National Geographic story leaves out the facts regarding the complex web of geo-political interests that make the UAE an important ally for the West, nevertheless, the article paints an abysmal picture of Dubai’s royals and their international oligarchical supporters, as well as the plight of foreign workers in Dubai.

Slaves of Dubai is a short 15 minute documentary on the subject of Dubai’s foreign workers that was created for VICE Media Inc. by journalist and reporter, Ben Anderson. Mr. Anderson, who has worked for a plethora of large media outlets (BBC, the Guardian, The Times of London, the Discovery Channel, New York Times), has filmed multiple documentaries about the war in Afghanistan (Taking on the Taliban, Obama’s War, The Battle for Bomb Alley), so he is familiar with filming challenging stories under exceedingly difficult circumstances. But even Anderson was shocked by the inhuman conditions that workers in Dubai suffer through. Much of his documentary was filmed in secret, and it captured the most appalling and nauseating conditions. Pulling no punches, Anderson said that “it’s not an exaggeration” to refer to the workers as slaves.

Mr. Anderson interviewed workers from Bangladesh that labored in Dubai’s construction industry, poor men who went into debt to pay the $2,000 in fees allowing them to work in Dubai. They were told by company recruiters that once they worked off their debts in a year, they could begin sending money home.

Instead they found themselves working for less than what they were promised, some were not paid for up to five months – all went deeper into debt. Their passports were seized, making it impossible for them to leave the country. Even if they had documents, they were too poor to arrange transportation out of the country. Their only option was to live in the squalid worker’s camp and labor at the jobs provided by the unscrupulous and crooked bosses that had hired them. In effect they became modern day indentured servants.

In her 2011 article for the Guardian, Dubai’s skyscrapers, stained by the blood of migrant workers, reporter Nesrine Malik described Dubai as; “a place where the worst of western capitalism and the worst of Gulf Arab racism meet in a horrible vortex. The most pervasive feeling is of a lack of compassion, where the commoditization of everything and the disdain for certain nationalities thickens the skin to the tragic plight of fellow human beings.”

It goes without saying that IZEL was built by the exploited foreign workforce told of by ABC, National Geographic, Ben Anderson, and Nesrine Malik. One must wonder how many foreign construction workers fell, or jumped to their deaths while building the damnable 51-story Conrad Hilton Dubai (annually, hundred of foreign workers in the emirate take their own lives out of desperation). And that is the rub; Chicano artists and their circles have long advocated and upheld the rights of Latino workers in the United States—but there is no concern over the plight of the wretched immigrant workers in Dubai?

There is more to Dubai’s politics than the heartless treatment given foreign workers. The UAE and the United States are allies, and as partners they have been maneuvering to dominate the region, both for its strategic geo-political importance and its vast oil and natural gas wealth. Detailing how this has been done is beyond the scope of this essay, but a few things are worth mentioning.

The New York Times reported that in 2011 the Obama administration encouraged the UAE and Qatar to ship weapons to the Libyan “rebels,” then fighting the government of Muammar Gaddafi. NATO forces blockading Libya had to be alerted by the U.S. not to interdict shipments. It soon became apparent that the arms shipments were going to extremist Islamic militias, some affiliated with al-Qaeda. When the U.S.-NATO war against Libya began on March 19, the UAE Air Force sent twelve of its jet fighters to participate in military operations. The war resulted in the overthrow and assassination of Gaddafi, and a fractured Libya under the heel of extremist Islamic militias. Not surprisingly, the UAE, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and the U.S. are now working together to ship arms to the “rebels” in Syria, some of which are affiliated with al-Qaeda.

Once again, it is hard to imagine Frida Kahlo putting up with any of the above, though there is so much more I could write about. It should also be apparent how incongruous it is for Kahlo’s portrait to be hanging in club IZEL.

Let me be frank in my appraisal of contemporary Chicano art. It is far from its origins, and that in large part is what this article is about. The roots are still viable, though the foliage is looking peculiar and in need of pruning. The greater part of Chicano art is mired in tired clichés, as if portraits of “exotic” Latinas wearing traditional clothes and posing with antique pistolas says anything meaningful about our past, present, or future. The school has largely reduced itself to painting those scenes of lush tropical jungles filled with colorful birds and happy peasants that David Alfaro Siqueiros detested and refused to paint. Something more is required today, and that is also a reason for this article.

Art and identify politics make an ill fit, at least for me. I seek a more universal language. My attraction to Chicano art as a stronghold of realism still holds—though somewhat precariously. However, realism is not just a way of accurately depicting objects, people, and events. It is a deep exploration of the human condition. It gets at what it is to be human. It strives for the truth. That philosophy is central to this essay.