The Truth About Babylon Berlin

In the dead of night in 1929, a Steam Locomotive roars down the tracks to Berlin from somewhere in Russia. The mysterious train carries hidden cargo, tons of gold and a huge amount of deadly poison phosgene gas. But who are the senders and who are the recipients? Disparate forces and individuals in Berlin—monarchists, mobsters, social democrats, trotskyists and stalinists—all at odds with one another and aware of the secret transport, are absolutely desperate to get their hands on it. Their nefarious plots to capture the train and its payload form just one underpinning of the new German TV series, Babylon Berlin.

Never before have I written a review of a television show, and wouldn’t you know it, my first attempt is almost as long as Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. But then, Babylon Berlin is not your typical idiot box entertainment. So please enjoy my first, and possibly last stab at such criticism.

I have always had a passion for the art produced in Germany during the Weimar years (1919-1933), so I was thrilled to discover Babylon Berlin would depict that tumultuous period. This essay gives my view of the show thus far, its strong points and foibles, with a spotlight on the art and politics of the period.

The TV series has multiple characters and plot lines, and a few anachronisms I’ll write off to artistic license. The narrative of this detective noir period piece is engaging enough that you don’t need to know the actual history behind the drama’s backdrop—but it certainly helps. My essay is not a timeline for the show, and though long and detailed, I will not be covering everything presented in the series. However, my article will contain major “spoilers.”

The main character of Babylon Berlin is Inspector Gereon Rath (played by Volker Bruch). A man in his early thirties, Gereon is a well-mannered member of the Cologne police force. A combat veteran of WWI, he quietly suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder, and secretly self-medicates when high stress situations cause him to tremble uncontrollably.

For that purpose he is most likely using the cough syrup containing heroin then produced by Bayer, Germany’s chemical and pharmaceutical company. Perfectly legal at the time, heroin based medicinals were widely used as a painkiller throughout the country. Rath is also a man struggling with his Catholic faith, both for the loss of his brother Anno on the battlefield, and for his ongoing affair with his brother’s wife Helga Rath.

Engelbert Rath, a senior official at the Cologne police force, transferred his son Gereon from the Cologne police to the Alexanderplatz police HQ in Berlin, also known as the Rote Burg (Red Castle) for its red walls.

Gereon is partnered with vice squad leader, Bruno Wolter (played by Peter Kurth). A gruff, 44-year-old bear of a man and fellow veteran of the Great War, Bruno is a loyal friend and colleague—provided you’re on his side.

Engelbert has a clandestine mission for his son Gereon: hunt down the underworld pornographers who are blackmailing politicians with surreptitiously shot film of them engaged in sadomasochistic acts. It is suggested that the Lord Mayor of Cologne, Dr. Adenauer, is one of the victims of the extortionists. To preserve the stability of the government, and because Adenauer is a family friend, Engelbert wants Gereon to find and destroy the incriminating film.

Konrad Adenauer was in fact an actual historic figure. A devout Catholic, he was not only the Mayor of Cologne during the Weimar years, but at the close of WWII was a co-founder and leader of the center-right party, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU, the same party of Germany’s current Chancellor Angela Merkel).

Adenauer was also the first Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) from 1949 to 1963.

Before Babylon Berlin was shown on German TV, series producer Stefan Arndt explained the plot to Bild-Zeitung. Despite knowing the actual story, the tabloid published a sensationalist piece around the question, “Is it really necessary to make the father of the Federal Republic a sadomasochist?” It should go without saying that the real Adenauer was never blackmailed for being a sadomasochist. The controversy went nowhere when the TV series eventually showed Mayor Adenauer to be completely innocent.

The characters, events, fashion, political movements, street names, even the buildings in Babylon Berlin are rooted in historical reality. The realistic digital recreation of Berlin’s Alexanderplatz is one such example. It evoked the hustle and bustle of the modern metropolis that was Berlin in 1929; but one has to make exception for the fact that two of the buildings depicted in the scene had not yet been built. The Alexanderhaus would be constructed in 1930 and Jonass & CO erected in 1934. Chalk it up to artistic license.

There is some bending of the truth in Babylon Berlin, the digital Alexanderplatz is a good example. Another is the hijacked train so central to the story, a German DRB Class 52 steam locomotive, which would not be built until 1942. Other examples exist, but I’ll let you find them. This brings to mind the often quoted but horribly misunderstood words of Pablo Picasso, who once quipped, “Art is a lie that makes us realize truth—at least the truth that is given us to understand.”

Much of the outdoor shots in Babylon Berlin were filmed at Studio Babelsberg. Filming took place on Neue Berliner Straße (New Berlin Street) part of the studio’s Metropolitan Backlot. A modular set of four streets with different architectural styles, nearly the entire set is comprised of false front buildings. The Babylon Berlin set included a façade of the Moka Efti nightclub on a broad paved avenue with modernist style buildings. Around the corner was a recreation of the drab slums where working class people would have lived, replete with cobblestone streets. Actor Volker Bruch called the set “a chameleon.”

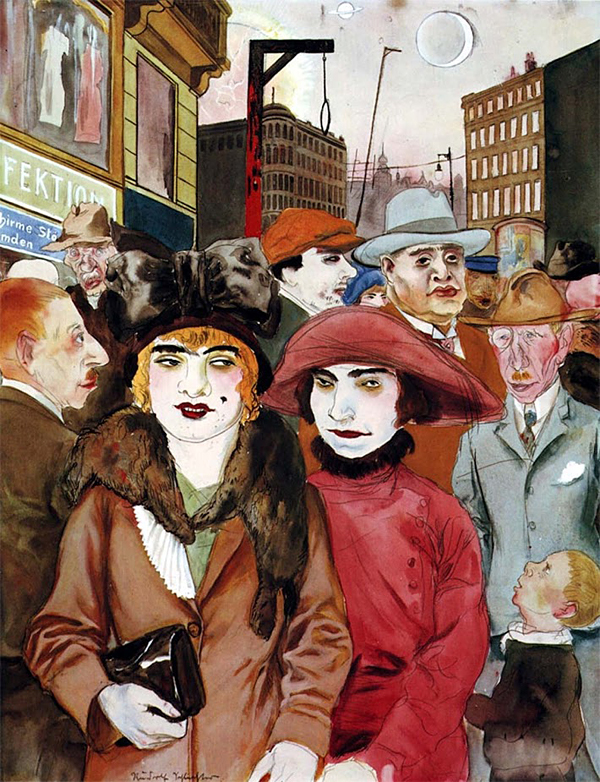

Viewing Babylon Berlin is like watching German Expressionist paintings come to life; the 1926 watercolor Hausvogteiplatz by artist Rudolf Schlichter is one such work. The title refers to an underground railway station in the central locality of Mitte, Berlin. Schlichter placed a gallows in his cityscape, a prescient statement on the doomed city. In 1937 the Nazis declared him a “degenerate” artist and in 1939 they forbade him from painting.

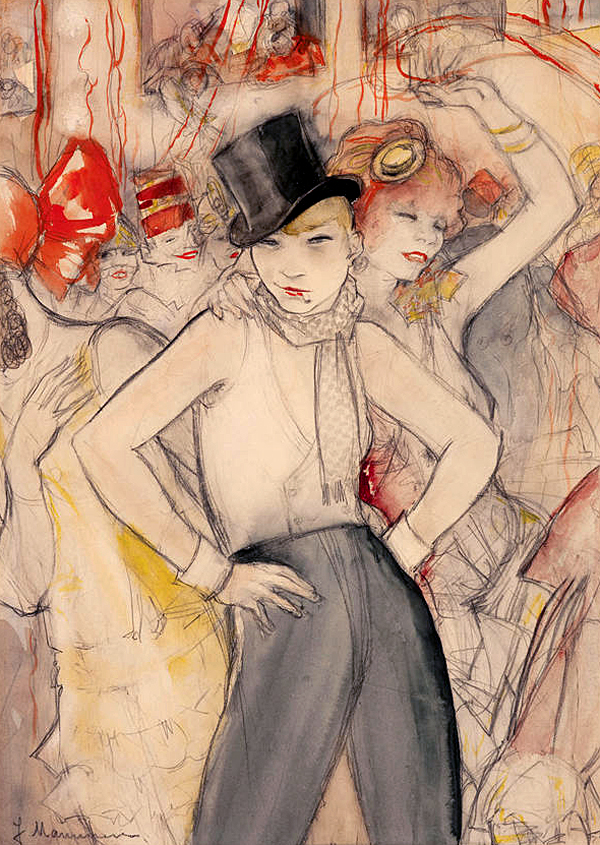

Jeanne Mammen was involved in the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement so many German artists were a part of at the time. It was a rejection of Expressionist idealism and a turn towards social and political engagement. Mammen was known for drawings in pencil, pen, ink, and watercolor washes that focused on women; in retrospect her drawings of bohemian women in Berlin’s cafes, including lesbian nightclubs, seem most remembered.

Sie Repräsentiert (She represents) was a 1928 drawing of women in a lesbian night spot; published in the pages of the weekly satirical magazine, Simplicissmus, the editors were actually the ones to title the drawing. They attached the following text; “Daddy’s a state prosecutor, Mummy sits in the state parliament, I’m the only one in the whole family with a private life!”

Mammen once said, “I have always wanted to be just a pair of eyes, walking through the world unseen, only to be able to see others. Unfortunately one was seen…” And those who saw her were the Nazis. Reading their scathing denunciations after her last public exhibit in 1933, Mammen made a choice. She entered into self-imposed isolation, what Germans called “internal exile.” She withdrew to her studio and worked there in absolute secrecy, never to exhibit, publish, or speak of her art. Miraculously, the Nazis never came after Mammen. She survived the war, and died in 1976 at the age of 86.

There is some gratuitous sex and violence in Babylon Berlin, which at first had me thinking the show would be just another titillating TV sensation. But the attention paid to costumes, architecture, historic events and other details kept me watching, and it paid off. Aside from being an over the top noir thriller with a labyrinthine plot, the series also serves as a basic primer on the Weimar years.

A modest political understanding of the Weimar Republic years will help you figure out the historic setting of Babylon Berlin, which is why I wrote this essay.

As WWI drew to a close, support for Kaiser Wilhelm II in Germany collapsed; at the time his Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and General Erich Ludendorff were in practice running a military dictatorship. In 1918 the anti-monarchist November Revolution broke out, the Kaiser abdicated, and a left-leaning provisional government filled the vacuum.

Then the Spartacist uprising, led by the just founded Communist Party of Germany (KPD), tried to overthrow the government, which in turn unleashed the pro-monarchist army and the right-wing Freikorps (Free Corps) paramilitary to crush the uprising. The Weimar coalition government was founded on Feb. 6, 1919, and on June 23, 1919, it signed the Versailles Treaty, formally ending WWI.

The Versailles Treaty banned armored vehicles, heavy artillery, submarines and military aircraft of any kind being possessed by Germany’s Reichswehr (the armed forces—”Reich” meaning empire or realm, and “wehr” meaning defense). The Reichswehr was limited to 100,000 men and prohibited from manufacturing and stockpiling chemical weapons.

To the monarchists, militarists, and extreme rightists, those in the Weimar government became known as the “November criminals” for “stabbing the German army in the back” and for signing the Versailles Treaty. Yet the Weimar state was reliant upon the pro-monarchist armed forces and their counter-revolutionary Freikorps allies for security.

Confused yet? History isn’t nearly as serpentine and convoluted as Babylon Berlin’s narrative, so stop fidgeting and pay attention, I’m setting the stage for the drama. The TV series traces the tensions between the weak Social Democracy of Weimar and the reactionary generals of the Reichswehr that sought its downfall.

The TV series focuses attention on the little known Schwarze Reichswehr (Black Reichswehr), a shadow military the pro-monarchist generals set up to circumvent the Versailles Treaty and illegally rearm Germany. The Black Reichswehr was allied to multiple paramilitary units like the Freikorps, Der Stahlhelm (Steel Helmet), and Die Organisation Consul (Organization Consul or OC).

By 1919 there were 103 Freikorps formations and by 1923 an estimated 1.5 million men had participated in them. [1] In open violation of the Versailles Treaty, Steel Helmet alone had 500,000 men under arms by 1930. The OC assassinated the Weimar government Minister of Finance Matthias Erzberger in 1921, and the Foreign Minister Walther Rathenau in 1922. These types of paramilitaries would eventually join with the fledgling fighting force of the Nazi Party, the SA or Sturmabteilung (Storm Detachment).

In episode 1 of Babylon Berlin a train is hijacked by followers of Leon Trotsky before it reaches Berlin, they want to send its cargo of gold to their exiled leader in Turkey in order to finance the overthrow of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin.

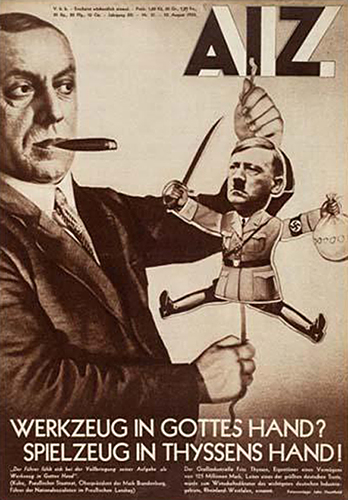

In a separate plot unbeknownst to the rebel communists, industrialist Alfred Nyssen (played by Lars Eidinger), financed the smuggling of phosgene gas into Germany on the same train in order to rearm his Black Reichswehr accomplices.

Nyssen is a stand-in for the historical figure Fritz Thyssen, who with fellow industrialists Friedrich Flick, Günther Quandt, Gustav and Alfried Krupp, and others, were the billionaires plotting against the Weimar Republic. They would later become the financial backbone of the looming Hitler regime.

The fictional hijacking in Babylon Berlin aside, history shows us that Trotsky (the founder of the Soviet Red Army) was expelled from the Russian Communist Party by Stalin and sent into exile. He ended up living in Turkey on the island of Prinkipoin before traveling to Mexico in 1937 where he and his wife lived for a short time with Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo. Eventually a Stalinist assassin armed with an ice axe attacked Trotsky in his home in Mexico on June 7, 1940; he died from his wounds the next day.

The hijackers in episode 1 are a fictitious secret Trotskyist cell in Berlin called “Red Fortress,” led by Alexei Kardakov (played by Ivan Shvedoff). They run a subversive printshop where they hold meetings and print revolutionary propaganda.

In one scene they are printing flyers that read: “Workers! May 1: Step out and fight for a Fourth International and the World Revolution! ‘Stalin is the gravedigger of the revolution.’ – Leon Trotsky” (anachronism alert: the Trotskyist Fourth International would not be founded until 1938).

In the TV series Kardakov lives above ground as a violinist, and gets word of the gold from his lover Lana Nikoros, a popular Kabarett singer in Berlin (played by Severija Janusauskaite). But things are never as they appear.

Nikoros is the backwards spelling of Sorokina, it is an alias for the mysterious Countess Svetlana Sorokina, seducer and betrayer of communists, monarchists, and social democrats alike. It’s not even known if the enigmatic Sorokina is actually a Countess, the only certainty is that she’s after the gold cargo on the train, the “Sorokin gold,” the untold wealth of the Russian oligarch Sorokin family.

In episode 2 of Babylon Berlin, Nikoros/Svetlana has a self-serving plan to take the “Sorokin gold” from the Trotskyists, she betrays Kardakov to the Soviet diplomat in Berlin, Colonel Trochin (played by Russian actor Denis Burgazliev). Trochin is an official in Stalin’s secret police, members of which he sends to murder the Trotskyists of the “Red Fortress” as they work in their printshop.

Kardakov witnesses the massacre and narrowly escapes to become one of the most abused characters in film history; at various moments in the TV series he’s shot, falls out a window from a great height into a pool of water, dislocates his ankle, is stabbed, and is exposed to poison gas. None of this was meant to be comedic, but sheesh!

History gives us a slightly different picture. The Soviet ambassador to Germany from 1923 to 1930 was Nikolay Krestinsky, a leading communist that ran afoul of Joseph Stalin by being an admirer of Trotsky. In a move most likely to get Krestinsky out of the way, Stalin sent him to Berlin as ambassador. It’s implausible that a man close to Trotsky would see to the murder of his fellow Trotskyists. In the end Krestinsky returned to Moscow where he was arrested, given a sham trial during the Stalinist Great Purge, and executed in 1938.

The opening train scene made me think me of the short 1927 film by Walter Ruttmann, Berlin, Die Sinfonie der Großstadt (Berlin: Symphony of a Great City). His film showed the approach to Berlin through the window of a fast moving Steam Locomotive—dizzying shots of villages, bridges, transmission towers, factories, blurred by speed and interspersed with shots of the train’s mechanical components at work.

The Futurist spectacle praised modern technology, but when the train pulled into the station, the sights, sounds, and people of the city became the focus. “Symphony” is a visual chronicle of 1927 Berlin, and I’m sure the makers of Babylon Berlin examined the film again and again. Ruttmann was also the cinematographer for German film classics like Fritz Lang’s 1924 Die Nibelungen: Siegfried, and Lang’s Metropolis (1927).

Viewers of Babylon Berlin may think the animated closing credits are current digital studio productions. They look contemporary, but they are in fact excerpts from silent animated films Ruttmann created in the early 1920s.

From his four-part series titled Lichtspiel Opus (Play of Light Opus), segments from his Opus II (1923) and Opus IV (1925) run under the credits while clips of the show’s soundtrack are played. Ruttmann created his works by applying oil paint with a brush directly on a glass pane set up beneath an animation camera. An image was painted, filmed, altered, filmed again—repeating the entire process frame by frame until the film’s completion. Ruttmann was apparently the first to create animation in this manner.

Unlike many of his compatriots in the arts, Ruttmann didn’t leave Germany when the Nazis took power, despite the fact that the film studios he worked for had been taken over by the Nazis. He helped edit Leni Riefenstahl’s 1935 The Triumph of the Will, and was put to work directing propaganda films.

While producing one such film on the frontline with Russia in 1944, he was seriously wounded and died in a Berlin hospital from his injuries. His career begs an important question; how does an avant-garde artist come to work with brutal totalitarians? I think this unanswered question, one of many posed in Babylon Berlin, is the reason why Walter Ruttmann’s works were included in the series.

There isn’t a better artwork to illustrate my article on the Babylon Berlin TV series than Weimarer Fasching (Weimar Carnival), a painting created by Horst Naumann (1908-1990). It could have been commissioned by producers of the show, though it was painted between the years 1928 and 1929. It offers a kaleidoscopic view of Weimar Germany, juxtaposing the acceptable with the intolerable. There’s a line of Kabarett dancers in top hats, and the man who was on his way to becoming the heavyweight champion of the world, Max Schmeling. But the painting also contains sinister images.

Paul von Hindenburg is depicted, at the time of the painting he was Reich President, but in 1933 he would appoint Adolf Hitler chancellor. Over Hindenburg’s shoulder there’s a graveyard, under him, the gaping maw of a bank vault, to his right there’s a Zeppelin airship, the type used to drop bombs during the Great War. At top left there’s a fleet of French biplanes, at the bottom of the painting a soldier in a gas mask slogs across a battlefield strewn with tanks. But it’s the central figure that commands our attention; a soldier wearing a red jacket, monocle, and a swastika embellished steel helmet. He’s probably in the Freikorps, who, to identify their units, would paint an identifying symbol on their helmets before entering a street fight. This is one of the earliest German paintings depicting a swastika that I know of.

Naumann was a painter and graphic designer who studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Dresden until 1927; Otto Dix was one of his professors. In 1927 Naumann joined the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), and soon after started painting Weimar Carnival. In 1929 he joined the KPD’s Association of Revolutionary Visual Artists. In 1931 he worked at a commercial printing company designing billboards, postcards, brochures, and posters. In 1934 the Nazis arrested him and sent him to a detention center for left-wing political prisoners. In 1939 he was press-ganged into the Nazi army to work in a labor battalion. After the war Horst Naumann became famous for his numerous stamp and poster designs, with his posters for German Zoos being most remembered.

Episode 4 of Babylon Berlin shows scenes right out of a history book as Gereon and Bruno are caught up in violent demonstrations. May 1, 1929, Blutmai (Bloody May) was a real life event in German history where 33 civilians were shot and killed by a security force of up to 13,000 armed police unleashed by the Weimar government. The episode shows Gereon, Bruno, and a squadron of police carrying out a door to door raid on the civilian population to confiscate firearms; it is a prescient scene.

In 1928 the Weimar government passed strict gun control laws for “the maintenance of public security and order.” Citizens were required to register, and or surrender their guns to the police or face jail time. It should go without saying that these laws would have disastrous consequences; when Hitler took power in 1933 the German people were already largely disarmed. [2]

The actual history of Bloody May shows that the Weimar government in 1928 lifted the ban on public speeches given by Adolf Hitler.

Not surprisingly Hitler then gave a speech in Berlin and a riot ensued. The government responded by banning all public political speeches and rallies, including the International Workers Day demonstration planned by the German Communist Party.

Virtually on the eve of May Day, April 29, 1929, Der Abend (The Evening), the late edition of the Social Democratic Party newspaper Vorwärts (Forward), featured a headline that read, “200 dead on May 1? Communists prepare for crimes.” It was of course propaganda designed to discourage people from attending May Day, but it was also a way to slander the KPD.

That very edition of Der Abend appeared in episode 5 of Babylon Berlin during the scene of an emergency meeting between Berlin officials—Police Chief Karl Zörgiebel, Mayor Gustav Böß, and head of the Political Police, August Benda (all of them Social Democrats).

The Chief of police throws the edition of Der Abend on a table and asserts, “Our own party organ says 200 dead!” To which Benda replies, “That is false information.” That the creators of the TV series would use a duplicate copy of the May Day 1929 edition of Der Abend, shows how far they went in recreating the ambience of the Weimar years.

May 1, 1929 proved fatal to the Weimar government. After the mass killing, the injuring of 200, the arrests of more than 1,200 people, and states of emergency declared in the working class districts of Neukölln and Wedding, a deep chasm opened up between the social democrats and the hard left.

The Communist Party of Germany (KPD) resolved to fight the “social fascism” of the Social Democratic Party. Ultimately, disunity on the left gave the fascist right an opportunity to march into power in 1933.

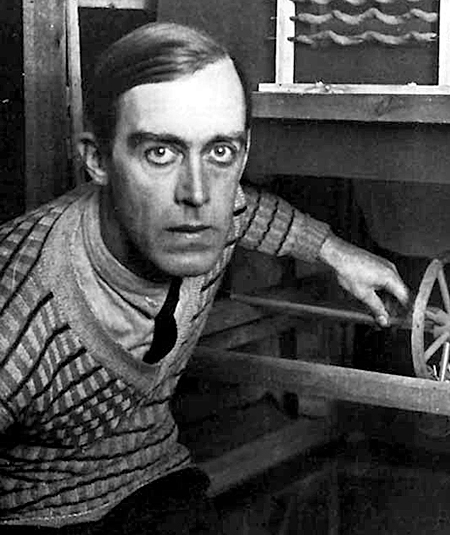

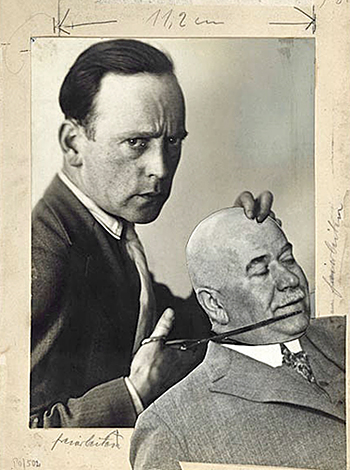

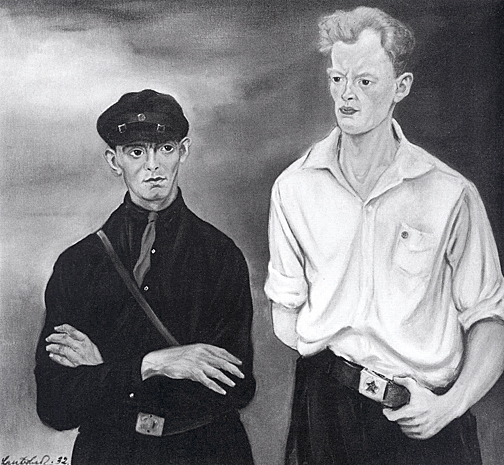

One painting that depicts the divided Germany of the period is the 1932 oil painting Die antifaschistische Jugend (The antifascist Youth) by Carl Lauterbach.

There’s not much information about the painting but it’s likely a portrait of young members of the Roter Frontkämpferbund (Alliance of Red Front-Fighters), a militia founded to fight enemy political rivals of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD).

Around this time Lauterbach began to paint exclusively in black and white, because in his words the Nazis took away the colors of joy. In Babylon Berlin the type of young men Lauterbach painted would be among the militants shown battling the police during Berlin’s 1929 Bloody May.

Lauterbach was a member of the Assoziation revolutionärer bildender Künstler Deutschlands (Association of Revolutionary Visual Artists of Germany), the group of artists who belonged to the KPD. Postwar he claimed the Nazis banned his art and declared him a “degenerate artist.” Lauterbach was celebrated in his home city of Düsseldorf—the City Museum of Düsseldorf awarded an annual “Carl Lauterbach Prize for Social Graphics.” However, history does not take kindly to liars. In 2012 the City Museum of Düsseldorf posted the following:

“Contrary to his later self-portrayal as a dissident and artist of resistance, Lauterbach has been involved in about 40 exhibitions in Germany and the territories occupied by Germany between 1933 and 1943, including at the organized by the Wehrmacht art exhibition for German soldiers in Paris. Lauterbach had no professional ban nor were his pictures considered ‘degenerate.’ Since 1934 he was a member of the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts.” [3]

The Reich Chamber of Fine Arts (Reichskulturkammer or RKK) was founded by Nazi Minister of Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels. Its mission was to control the cultural life of Germany. Whatever your creative field, cinema, theater, painting, literature, etc., you had to join the RKK in order to work, but first you had to have an official Ariernachweis, a Nazi certificate proving you were of the “Aryan race.” It appears that Carl Lauterbach successfully hid or denounced his red background to climb aboard the Nazi death machine.

Returning to the narrative of Babylon Berlin; ultimately Gereon Rath and Bruno Wolter report directly to the head of the Political Police, August Benda (played by Matthias Brandt).

Benda is an ardent supporter of the Weimar government. Charitable and kind-hearted with people, he’s a relentless investigator, and suspects certain people are out to overthrow the republic.

Benda is also Jewish, and with Germany rushing headlong towards a dark future, he is a marked man. He believes Bruno might be involved with the Black Reichswehr, and so he has Bruno’s assistant, Stephan Jänicke (played by Anton von Lucke), spy on the vice squad officer.

It’s ironic that the role of Benda is played by actor Matthias Brandt; here again cinema is entwined with real life. Brandt is the youngest son of Cold War politician Willy Brandt, who was the leader of the Social Democratic Party from 1964 to 1987 and served as the Chancellor of West Germany from 1969 to 1974. Willy Brandt was a supporter of the Vietnam war and was as anti-Communist as the fictional character of August Benda.

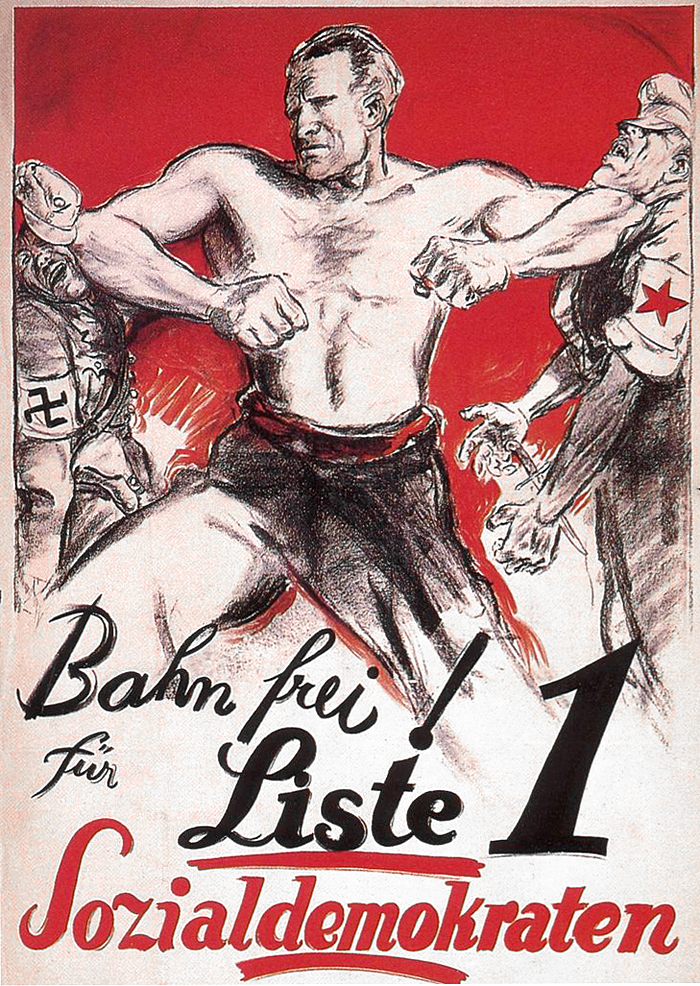

A historic poster that perfectly illustrates Benda’s political position can be found in a 1930 propaganda street poster for the Social Democratic Party (SPD). The poster was issued for the German federal election of September 1930, it reads: “Clear the Way for List 1 Social Democrats.” The visual message is unmistakable, a muscular working man symbolizing the SPD elbows out Communist and Nazi party cadre, but the election results were somewhat different. The SPD remained the largest party in the Reichstag with 143 seats, but the Communists won 77 seats and the Nazis won 107. Just three years later when Hitler took control, the Nazis would ban the Social Democratic Party. It remained banned and underground until the war ended in 1945.

A 23-year-old woman named Charlotte Ritter (played by Liv Lisa Fries) is also one of the primary characters in Babylon Berlin. She lives with her family in Neukölln, a working class borough in the southeastern part of Berlin.

Between poverty and her dysfunctional family, her life is fairly miserable. Love for her little sister Toni and an irrepressible optimism are her only possessions. In the evenings Charlotte works as an off-the-books prostitute in the infamous Berlin dance club, the fashionable Moka Efti.

Charlotte is hired at Red Castle police HQ to catalog photographs of murder victims for the Criminal Investigation Department, headed by a man named Gennat.

Historically speaking, Ernst Gennat was the director of the Berlin Criminal Investigation Department. A brilliant criminologist, he coined the term Serienmörder (serial killer), introduced the idea of profiling, and was one of the first to insist that a crime scene must not be tampered with. Gennat solved 298 cases during his career.

Called the “Buddha of Alexanderplatz” by fellow officers because he weighed in at 300 pounds, the nickname carried over to the Babylon Berlin Gennat character, who was of slightly less girth. I should also mention that Charlotte Ritter’s job, that of cataloging photographs of murder victims to create a national registry of violent deaths, was an idea developed by Gennat.

History notes that Charlotte’s Neukölln was a stronghold for the Communist Party of Germany (KPD). In 1926 Joseph Goebbels, then a regional commander for the growing Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist German Workers’ Party), or Nazi Party (which had only 49,000 members in all of Germany at the time), staged a march into Neukölln that culminated in a bloody skirmish with communist militants. In 1926 there were little more than a few hundred Nazis in Berlin, a city Goebbels called “the reddest city in Europe besides Moscow.”

Charlotte helps her destitute friend Greta Overbeck (played by Leonie Benesch) land a job as a full-time maid with the Benda family. Greta is loyal, apolitical, and very naive. She joins Jänicke and Charlotte at Berlin’s Lake Wannsee for a swim and meets Fritz and Otto, two young communists who like insulting fat cats and bankers. Greta develops romantic feelings for Fritz that will have disastrous consequences.

The scenes of Charlotte, Greta, and friends at Lake Wannsee were obviously modeled after Menschen am Sonntag (People on Sunday) a black and white silent film created in 1930 by Curt and Robert Siodmak. The film was central to the advancement of modern cinema in Germany. Later on in the Babylon Berlin series, Charlotte is seen unaccompanied in a crowded movie house watching Menschen am Sonntag.

Babylon Berlin took artistic license with the Moka Efti nightclub, which was a historic cafe in Berlin named after its Greek-Italian owner Giovanni Eftimiades. It enticed Berliners with strong coffee and an “Egyptian Music Salon” where jazz played and refreshments were taken. Entertainment and perhaps a bit more had crowds flocking to the club. Despite what was shown in the TV series the real Moka Efti did not have a brothel in its basement. But it did have the latest technology, a passenger elevator called a paternoster lift. While you don’t see such a lift in the TV series Moka Efti, one appears in the Red Castle HQ. Charlotte and Gereon meet for the first time when they disembark from a paternoster and bump into one another, spilling their work files.

In the TV series Edgar “the Armenian” (played by Mišel Maticevic ), owns and runs the Moka Efti. A debonair man of few words, the Armenian is a ruthless mobster who has bribed, intimidated, blackmailed, and murdered his way to the top. His corrupt grip is felt in the police force and in the highest levels of government.

Gereon has noticed his footprint in every serious crime he’s investigated, yet, the Armenian is oddly protective of Gereon, a man he could have done away with on numerous occasions—and yes, Edgar is after the “Sorokin gold.”

I noticed something compelling about Edgar’s office in the Moka Efti nightclub, there are pictures of Armenian relatives or friends hanging on the walls. Given that the Armenian Genocide took place during WWI and the Ottoman Turks were wrapping up their butchery in 1923, this speaks volumes about Edgar’s temperament and may account for his being a patient of the mysterious Doctor Schmidt. As a native of Los Angeles, I’ll tell you that the Armenian population in my city is as high as 360,000, and so the issue of the Armenian Genocide is especially poignant. Every April 24th Armenians commemorate the victims with a huge march on the streets of L.A., marking the genocide that began in April of 1915.

In the TV series the unconventional psychologist named Doctor Schmidt (played by Jens Harzer), treats “shell shocked” WWI vets through hypnosis and drug therapy. His work touched the lives of many and as it turns out he healed the Armenian, administers to members of the Black Reichswehr, and has a keen interest in Gereon Rath. The character of Schmidt is woven through the whole of Babylon Berlin, and he plays a major role in the calamitous end of series two. One is left wondering if Schmidt is a saint or a sinner.

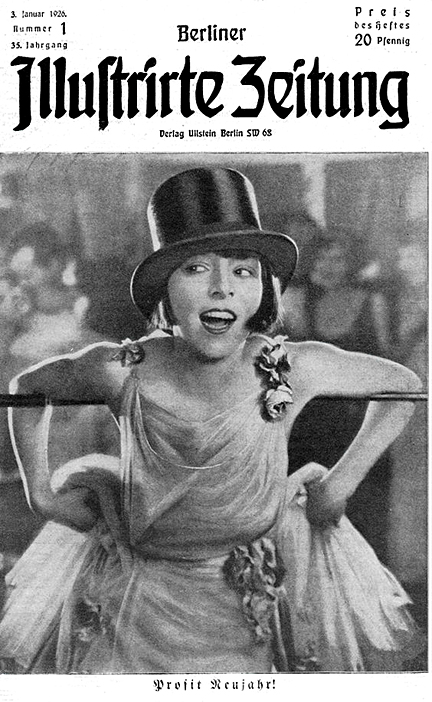

One of the highlights of the Babylon Berlin series is when Kabarett performer Nikoros (Svetlana Sorokina’s alter ego), entertains the crowd at the Moka Efti by singing the gloomful song Zu Asche zu Staub (To Ashes, to Dust). She’s in androgynous black leather drag and accompanied on stage by a wild troupe of exotic dancers dressed in banana skirts. The crowd sings along and follows the pantomime, swaying and gyrating in drunken revelry. But it was not the first time that banana skirts had been seen.

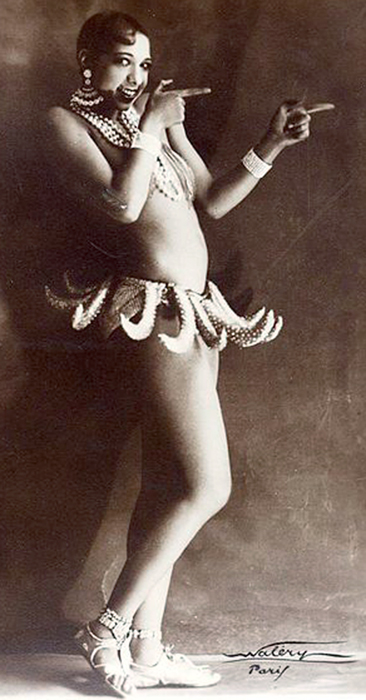

In real life the American dancer Josephine Baker made her way from the U.S. to Paris, France in 1925. At 19 she caused a sensation with her exotic dancing when she debuted in the Black American musical revue “La Revue Nègre.”

That same year she become a star at the Folies Bergère performing her “Danse Sauvage,” a dance where she wore little more than “a costume of 16 bananas strung into a skirt.” [4]

In 1926 Baker performed her show in Berlin, and while Babylon Berlin makes no mention of her, the dancers at the Moka Efti are a tribute to her nonetheless. When the Nazis came to power Baker was banned from performing on stage in Germany—she moved back to Paris. When the Nazis invaded Paris she joined the French underground.

Josephine Baker would die in Paris on April 12, 1975 at the age of 68. The story of the legendary Baker would make a heart-stirring movie, if only there were any decent script writers, directors, and producers left in Hollywood.

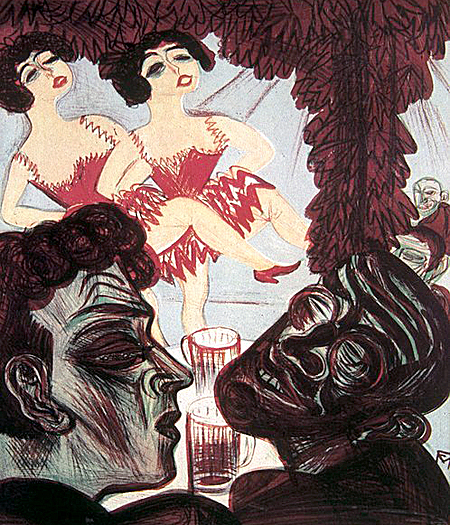

American jazz swept Germany in the 1920s and set roots there. People listened to Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong on the radio, the Charleston became a dance craze, and Germans formed their own jazz combos and orchestras like the Weintraubs-Syncopators. Artists noticed jazz as well. Otto Dix created two paintings that showed jazz musicians, a 1922 self-portrait titled An die Schönheit (To Beauty), and a 1928 triptych titled Metropolis, which had as its central panel a depiction of elites being entertained by a jazz combo.

Even though the majority of Americans today think jazz is out of vogue, some of us still consider it an indispensable musical form. But how does jazz have political and social implications? The answer in part is found in German history.

In 1933 the Nazis targeted jazz for its links to African-Americans. In 1935, to stop “racial pollution” they banned jazz being played on German radio.

In 1938 they organized the Entartete Musik (Degenerate Music) exhibition to denigrate jazz as well as Jewish classical music composers like Gustave Mahler and Felix Mendelssohn.

Many young Germans belonged to the Swingjugend (Swing Youth) counter-culture, where playing jazz in underground clubs was an act of defiance. Eventually the Nazis had enough, and starting in 1941 they began mass arrests of Swing Youth, sending them to concentration camps.

It is amazing how many times Babylon Berlin will send you to the internet to research something viewed in the show, take the following song for example. In the second season’s final episode, Nikoros/Svetlana resurfaces as a Russian performer in a Paris nightclub. She sings a mournful song in Russian as an old paramour enters the club. At the end of the song, in keeping with its grief-stricken lyrics, she pretends to cut her throat using a prop theatrical knife.

The song Nikoros sang was Gloomy Sunday (titled Vaskresenje in Russian). The original Gloomy Sunday however was written and performed by Hungarian pianist and composer Rezso Seress in 1933; in Hungarian the title was Szomorú vasárnap. The song was recorded by Paul Robeson in 1936 and then by Billie Holiday in 1941. Since then Gloomy Sunday has been vocalized by innumerable performers.

Overall the soundtrack for Babylon Berlin is possibly the biggest anachronism in the show—but truthfully, I love it. The ambient incidental music for Babylon Berlin was written by longtime collaborators Johnny Klimek and Tom Tykwer, one of the show’s directors. The two composed a contemporary score using electronica, strings, and piano, it is entrancing music that sounds both modern and reminiscent of the past. To me its most successful passages fuse techno with 1920s jazz; tracks like Dunkles Babel and Der Prangertag I find particularly striking.

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of the soundtrack was the participation of the English crooner and songwriter Bryan Ferry, who is remembered by many as the frontman for the 1970s glam art rock band Roxy Music.

Prior to punk rock in 1977, misfits like myself listened to the likes of David Bowie (Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars), and Roxy Music, which at the time included Brian Eno, who was a driving force behind the new electronic, ambient sound—some of which even influenced punk rock.

In 2012 Mr. Ferry formed the Bryan Ferry Orchestra and released The Jazz Age, a brilliant album of 1920s jazz renditions of his past hits. I have listened to this album innumerable times and I’m thrilled the songs Dance Away, Reason or Rhyme, Bitters End, Alphaville, Chance Meeting, and Bitter Sweet appear on the Babylon Berlin soundtrack. Best of all, in episode 10 of the TV show, Ferry makes a guest appearance as a jazz singer performing Reason or Rhyme at the Moka Efti.

While Ferry’s music is not actual jazz from the 1920s, it possesses its form, spirit and vitality, and the musicians of the Bryan Ferry Orchestra are no slouches either. The men of this retro-jazz ensemble have given themselves to the 1920s jazz style, and in my not so humble opinion, their music fits Babylon Berlin hand in glove. Watch the documentary The Making of ‘The Jazz Age’ to understand my enthusiasm for this music.

I have long complained that music in commercial films has become a hackneyed method of audience manipulation—a stupid and cheap one at that.

An example of what I’m talking about would be the music found in the 2001 “medieval adventure” film, A Knight’s Tale. Purportedly about 14th-century Europe, the soundtrack uses music from the likes of Queen (We Will Rock You), and David Bowie (Golden Years).

Yeah, because nothing says Middle Ages like rock n’ roll music. If you want just one example of the incandescent music of the medieval period, then listen to the works of Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179). Hollywood directors no doubt wither away when exposed to such divine sounds.

Filming the Moka Efti scenes for the TV series took place in an old silent film theater in Berlin-Weissensee called the Delphi. Opening in 1929, the hall had a stage, an orchestra pit, and a seating capacity of 900. It was closed in 1959 and served as a storage room until the production crew for Babylon Berlin recreated the Moka Efti dance hall in its interior. Since then the hall was renovated and today the Delphi is a performing arts house.

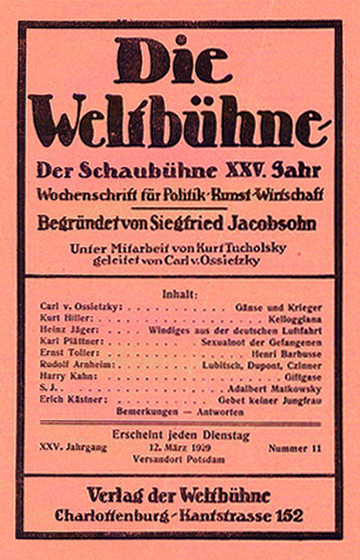

The German satirical writer Kurt Tucholsky, one of the most consequential journalists of the Weimar Republic, once wrote, “Expect nothing. Today: that is your life.” He could of written those words about any of the characters found in Babylon Berlin or, about us for that matter.

Tucholsky was a Jewish member of the Social Democratic Party prone to intense criticism of its leadership. In 1926 he was temporarily the publisher of the left-leaning journal Die Weltbühne (The World Stage), a journal dedicated to art, literature, and politics. It received a brief mention in Babylon Berlin when the dissident Austrian journalist Samuel Katelbach mentioned it in passing to Gereon Rath.

Of all the characters in the series, Samuel Katelbach (played by Karl Markovics) seems the most cognizant of where society was going. Putting aside his disheveled looks, as an independent reporter he knew the score. I’ve met a few like him in my lifetime, they work outside the mainstream to expose the truth no one wants to hear. A few listened in Germany, but not enough. Despite its historic impact Die Weltbühne had a small readership, but would pay a heavy price. While it’s amazing the series even named the journal, it did not mention its role in exposing a secret Reichswehr airbase in Lipetsk, Soviet Russia.

In episode 11 of Babylon Berlin, August Benda sends Gereon Rath and a police photographer named Gräf on an aerial mission over Lipetsk Russia to gather intelligence on the covert airbase. The info was needed to build a case for the arrest of army Generals suspected of violating the Versailles Treaty, which forbad Germany from having military aircraft. Two pilots fly the men over the base in a Junkers Ju 52 transport plane (anachronism alert: the plane wasn’t produced until 1931). In the hair-raising scene Gräf nearly falls out of the plane while taking photos, and is saved when Gereon grabs his arm as the plane dodges anti-aircraft fire. Action movie antics aside, it is a fact that the Reichswehr did maintain an illegal airbase in Lipetsk, Russia.

Shady Dealings in the Air was the daring 1927 exposé published in Die Weltbühne that revealed the Reichswehr had indeed violated the Treaty of Versailles by operating a massive secret airbase in Soviet Russia.

History has revealed that the Reichswehr contracted with the Soviets to run the base where future German pilots, as well as Soviet pilots, would receive combat training. The Reichswehr wanted to rebuild the Luftwaffe and the Soviets wanted German technical know how.

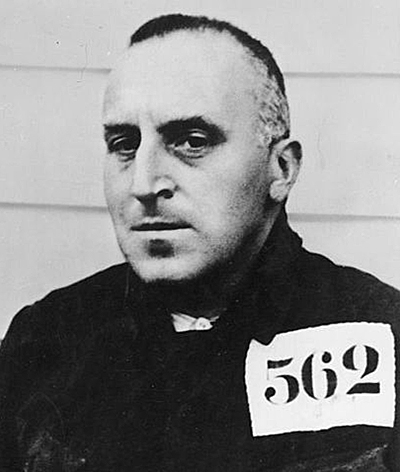

In 1931 the Weimar government charged the publisher of Die Weltbühne, Carl von Ossietzky, with treason and espionage for revealing the Lipetsk airbase. Convicted, he served 18 months in prison before being released in a 1932 amnesty.

When the Nazis took power in 1933 Ossietzky was rearrested and sent to the Esterwegen concentration camp where he was brutally tortured. As he continued to suffer in the camp he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1935. On the eve of the 1936 Berlin Olympics, he was transferred to a hospital under the watchful eyes of the Gestapo—soon after he was awarded the Nobel. The Nazis forbade German papers from publishing news of the award. Carl von Ossietzky died in 1938 as a consequence of his torture.

Liberal viewers of Babylon Berlin may think of the characters in the series associated with the Social Democratic Party (SPD) as the “good guys” and their monarchist opponents as stand-ins for today’s populists and nationalists. That viewpoint is ahistorical and ill-advised.

I will simply point out that in 1914 the marginally “socialist” SPD threw aside its principles, sided with Kaiser Wilhelm II, and voted in favor World War I. The horrific consequences are well known—18 million deaths and 23 million wounded. As a result the left-wing of the SPD abandoned the party en masse. But there is something else that may horrify liberals who believe the Weimar years were a liberatory time for women.

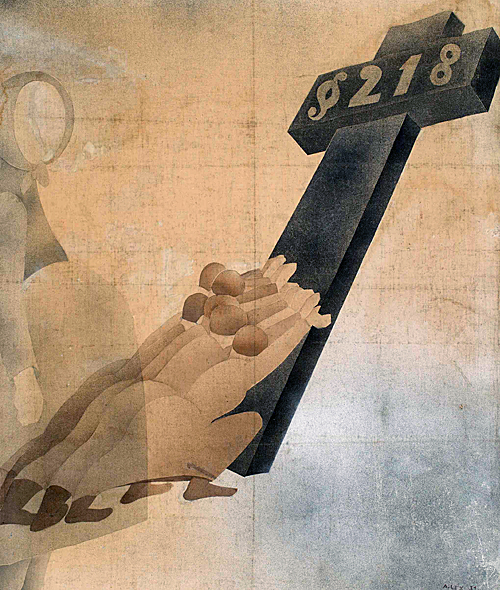

This may not mix well with the liberal image of daring young flappers with bob haircuts and the mythos of “new-found freedoms” for women, but an abortion ban was enshrined in paragraph 218 of the “progressive” Weimar constitution. It was primarily left-wing Germans that organized protests against the ban first added to the Criminal Code of the German Empire in 1871; the Weimar government could not, or would not, abolish paragraph 218.

The painter and photomontage artist Alice Lex-Nerlinger was part of Berlin’s left opposition to paragraph 218. In 1928 she became a member of the German Communist Party (KPD) and joined the Association of Revolutionary Visual Artists, or “Asso” for short, an arts group open only to members of the KPD.

While a painter she was most well known for her photomontage works à la John Heartfield. In 1931 she painted Paragraph 218, a blasphemous condemnation of the abortion prohibition that treated abortion as a punishable offense.

In 1933 the Nazis banned Lex-Nerlinger from making or exhibiting her art; she destroyed her own works to avoid arrest and persecution. Paragraph 218 is one of the few works by Lex-Nerlinger to have survived the period.

In episode 13 of Babylon Berlin, Greta Overbeck agrees to meet her boyfriend Fritz one evening at a Neukölln side-street meeting hall of the Communist Party. Anxious that Fritz is late, she paces back and forth in front of the hall when Fritz’s friend Otto arrives; they greet and wait together.

Yards away Fritz appears on the darkened street and calls to Greta, immediately he is surrounded by men who identify themselves as police. They grab him, he breaks away and runs towards Greta and Otto—and the police shoot Fritz in the back.

Greta and Otto watch in horror as the police toss the wounded Fritz into a car and speed off. Otto clutches Greta and they run off into the night to find safety.

The same episode reveals Bruno to be a chief planner of the Reichswehr Generals’ plot to overthrow the Weimar government and restore Kaiser Wilhelm to the throne.

Major General Kurt Seegers (played by Ernst Stötzner) and his fellow conspirators are in prison following their arrests for the Lipetsk airbase plot, but the guards are sympathizers and give Bruno easy access to the prisoners. Bruno Wolter gives his cohorts the detailed plans for the imminent “Prangertag” Putsch.

In episode 14 of Babylon Berlin, Otto meets Greta in front of the Benda family home to tell her that Fritz “didn’t make it,” and that the political police headed by her boss August Benda were responsible for his murder. Distraught, Greta said, “Tell me what to do and I’ll do it.” Walking away Otto said forebodingly “We will keep in touch,” implying the Communist Party would have a plan for retribution.

Meanwhile, Bruno is whistling Die Moritat von Mackie Messer (The Ballad of Mack the Knife) as he helps initiate the planned military coup on Prangertag (the Feast of Corpus Christi). It is almost comic relief that putschist Bruno Wolter would be whistling a tune from Bertolt Brecht’s Die Dreigroschenoper (The Threepenny Opera), but it does point out the sway left culture had in Berlin at the time. The fictional coup in Babylon Berlin seems to be modeled after the real life Küstrin Putsch of 1923.

In the TV series Bruno and his monarchist co-conspirators infiltrate a gala celebration at the Theater am Schiffbauerdamm in the Mitte district of Berlin. Mayor Gustav Böß as well as the French Foreign Minister Aristide Briand, and German Foreign Minister Gustave Stresemann (who were real life figures) are to be fêted with a command performance of The Threepenny Opera.

Bruno Wolter lies in wait with a scoped sniper rifle, hidden in the theater’s enormous crystal chandelier, but the mission goes awry and the coup is aborted. However… the plotters escape to try again another day.

The Threepenny Opera was actually first performed at the Theater am Schiffbauerdamm on August 31, 1928. Written by Bertolt Brecht and Elisabeth Hauptmann with music by Kurt Weill, it was meant as a Marxist critique of capitalism.

The very title expressed Brecht’s dream that theater should only cost a worker three pennies to attend. Brecht’s 1923 play Im Dickicht der Städte (In the Jungle of Cities) was disrupted by Nazis who tossed stink bombs at the actors on stage. The 1930 premiere of his opera Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny was likewise attacked.

When Hitler took power in 1933 the Theater am Schiffbauerdamm fell into decline and was closed in 1944. It was reopened after World War II and in 1949 Brecht and wife Helene Weigel established the Berliner Ensemble theatre company there.

In 1967 when I was 13-years-old, I purchased the first album by the psychedelic rock band, The Doors. It contained a composition that I fell in love with titled, Alabama Song. Someone older and wiser than I told me it was written by Brecht, so naturally I went to the library to find out who the guy was. I found that the song came from Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny—written by Brecht and Hauptmann and set to music by Weill. Even better, the library had a phonograph record that included Lotte Lenya singing the Alabama Song. I checked the record out from the library, took it home to play on my portable record player… and almost lost my mind. This entire experience sent me on a lifetime exploration of the Weimar years and German Expressionism. Hopefully, Babylon Berlin will inspire that same sense of discovery for others.

In episode 15 of Babylon Berlin, Greta seeks revenge for the murder of Fritz and agrees to work with the communists to help assassinate August Benda. She lets KPD member Otto into the Benda family home and helps him install a bomb in a drawer of August’s reading room desk; it will detonate when the drawer is opened. When the deed is done Greta flees for the train station, hoping to disappear into another city. At the station she sees an angry mob demonstrating against Mayor Gustav Böß, who is on the train.

Historic accounts of the real Mayor Böß show that he was embroiled in the “Sklarek scandal,” where he was accused of taking huge bribes from three wealthy Jewish clothing suppliers, the Sklarek brothers, who were charged with defrauding the Berlin City Bank. Nazi activists used the controversy to help push their anti-Semitic politics.

The mob is made of men from the SA (short for Sturmabteilung, Storm Detachment), the original fighting force of the Nazis. This is the first glimpse of uniformed Nazis in the Babylon Berlin series. Examining the disparate social forces and tensions that created the Nazi movement, rather than simply making the Nazis an immediate focus of the series, is what makes Babylon Berlin so noteworthy. As a viewer you sense the approach of fascism, but the writers and directors of the show chose to build up unease over 15 episodes; they kept the thugs with the swastika armbands backstage to great effect.

We know the ultimate fate of the characters in Babylon Berlin, but we still have to ask who will end up being a Nazi, and why. Will it be the typist, the doctor, the maid, club owner, or politician? What makes a Nazi, and how do you recognize fascist culture and politics? Watching the characters in the series you get a sense of their indifference and lassitude, but it’s really no different than our own. Back then, who knew what terrible future awaited Germany? Which one of you crystal ball readers today would like to predict where we’re headed now?

While many characters in the series are warm and approachable, there is still something unsettling about them; I want to like these people but hesitate, not knowing who they really are. They are “normals” in outrageously abnormal times, and they seem as out of order as the Stock Market would be in late 1929; it crashed and destroyed the German economy, sending millions into the arms of the Nazis. A few characters in the TV series already have an aura of malevolence about them; the words “banality of evil” describe them well.

Henrik Handloegten, co-writer and co-director of the TV series put it most succinctly in a recent interview; “One of the main reasons to make Babylon Berlin was to show how all these Nazis did not just fall from the sky. They were human beings who reacted to German society’s changes and made their decisions accordingly.”

Returning to the TV series, Greta is shocked to see Otto in the crowd dressed in the Brownshirt uniform of the SA; she stares at the mob and is horrified to see Fritz, and he’s also wearing the SA uniform. Greta realizes that her lover Fritz and his friend Otto were Nazis masquerading as communists, and they were using her to get at August Benda. Betrayed, she runs back to the Benda home in hopes of reversing her treachery, but just as she reaches the home the bomb she helped to plant goes off, killing Benda and his little girl.

There is much more in Babylon Berlin to write about, the last episode of season two is, shall we say, explosive; however, I’ll leave that for you to discover. The series is far from perfect, but the imperfections are thankfully few. I’ll ignore the brief LaLa Land-like dreamy dance sequence; I’ll let slide Gereon Rath’s infrequent swashbuckling exploits; I’ll even overlook the scene where a central character drowns and minutes after death is brought to life with mouth-to-mouth resuscitation—a life saving technique introduced in 1950. I’ll forgive these sins against cinematic realism because Babylon Berlin otherwise examines history with honesty and passion.

The show provides a solid argument that first-rate drama can be had from exploring real life history. I can’t tell you what a relief it is to watch a film that is not crawling with cartoon characters, super-heros, and wiggling femme fatales. Perhaps Babylon Berlin represents a return to conscientious, artful cinema, I’m praying that is the case. I’d be in heaven if a straightforward film about the German Expressionist artists and their showdown with the Nazis were to be made. But then, such a film will never be created, unless of course there’s someone foolish enough to provide me with a budget to produce it.

The 16 episodes of the first two seasons of Babylon Berlin are available to view on Netflix in the United States. It has been verified that the series has received funding for a third season, so the show will eventually have to deal with Hitler and the Nazis taking power in 1933. Based on the 2008 crime novel Der Nasse Fisch (The Wet Fish) by German author Volker Kutscher, the TV series was written and directed by Tom Tykwer, Achim von Borries, and Henrik Handloegten. The show had a budget of 40 million euros ($49 million U.S.), making it the most expensive TV series ever produced in Germany. By contrast on Feb. 13, 2018, Netflix cut a $300 million deal with American director Ryan Murphy (creator of American Horror Story) to produce films exclusively for Netflix.

I can happily say that one is much better off viewing Babylon Berlin.

————————

ADDENDUM:

[1] More info about the Freikorps: International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

[2] Stephen P. Halbrook: “Nazism, Firearm Registration, and the Night of the Broken Glass.” (PDF file). Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law, No. 3. (2009)

[3] Article about the artist Carl Lauterbach – Painter in Twilight: RP Online. Feb. 28, 2012. German language.

[4] Josephine Baker’s official website biography

FURTHER READING:

My review of the 2010 Long Beach Opera production of “The Good Soldier Schweik” holds plenty of information about Germany in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

My 2011 essay “Paul Fuhrmann’s ‘War Profiteer” focuses on the German Expressionist painter Paul Fuhrmann, as well as the Nazi Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition of 1937.

My 2013 “Echoes of Weimar” essay covers the works of two Weimar era artists, Barthel Gilles and Otto Dix. The article holds some surprising information about the two painters.

Excellent article on German Swing Youth and Nazi repression from the German website “20-2-40-Style-Syndicate.”

The Russian website “AirPages” offers an extensive and detailed examination of the Reichswehr secret airbase in Lipetsk, Soviet Russia.

Babylon Berlin is fairly exact in all sorts of background details, including antique firearms. The Internet Movie Firearms Database tells you what weapons appeared in the series.