Edward Hopper: A Retrospective

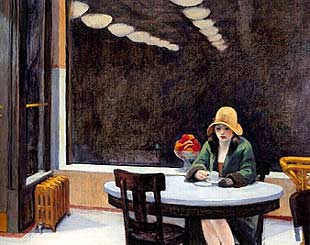

Edward Hopper (1882-1967) is the subject of a major retrospective at the Art Institute of Chicago, the last venue for a traveling exhibition that included stops at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the National Gallery of Art, Washington. Encompassing nearly 100 of the artist’s most notable prints and paintings, the exhibit features some of the artist’s most iconic canvases, New York Movie (1939) and Nighthawks (1942) to name but a few. As a youngster Hopper’s paintings provided me with an entry point into the art of the Great Depression period, and I recall as an adolescent being mesmerized by his works. So without hesitation I cite Hopper as one of my influences.

The figurative realist paintings of Edward Hopper continue to be extremely popular with the general public and a good number of critics. In 2004 the Tate Modern in London mounted an exhibition of Hopper’s works that turned out to be the second most popular show in the museum’s history – pulling in nearly half a million visitors during its three month run (a 2002 exhibit of paintings by Matisse and Picasso was the Tate’s most popular show). I think it’s a mistake to ascribe Hopper’s continued popularity to simple nostalgia, as I’m certain the allure of his work is based upon a modern audience seeing itself reflected in the portrayals of alienation he so often depicted. In essence Hopper was a social realist, and what he quietly revealed about late 20th century American society still rings true today. Conceivably, another explanation for Hopper’s lasting popularity might be found in his final written statement, published in the Spring of 1953:

“Great art is the outward expression of an inner life in the artist, and this inner life will result in his personal vision of the world. No amount of skillful invention can replace the essential element of imagination. One of the weaknesses of much abstract painting is the attempt to substitute the inventions of the intellect for a pristine imaginative conception. The inner life of a human being is a vast and varied realm and does not concern itself alone with stimulating arrangements of color, form, and design. The term ‘life’ as used in art is something not to be held in contempt, for it implies all of existence, and the province of art is to react to it and not to shun it. Painting will have to deal more fully and less obliquely with life and nature’s phenomena before it can again become great.”

Of course, Hopper made his statement when Abstract Expressionism was the dominant force in the American art scene, and more importantly, at a time when art elites had pronounced realist painting to be woefully old-fashioned – a viewpoint we are still largely saddled with today. But then, Hopper was impervious to the avant-garde movements that swept over the later half of the 20th century; Surrealism, Action Painting, Pop Art – all had absolutely no impact upon him whatsoever. Now that the chilly detachment of postmodernism has become the prevailing fashion in art, many are looking towards artists like Hopper for craft, beauty, technical virtuosity, and narrative without the tedious yoke of irony.

Hopper’s social realism was of a psychological bent, showing individuals who were estranged from each other and at odds with their surroundings – even his depopulated cityscapes suggested disquiet. Hopper’s evocative paintings provide just enough of a story to pull in the viewer, even while maintaining impenetrable mystery – one is never quite certain what the people in his canvases are thinking or doing. While Hopper’s themes often dealt with alienation they were never alienating, and despite the depictions of emptiness and seclusion, Hopper’s works somehow imparted – and still do – a deep and unshakable humanism.

As a student Hopper studied painting and illustration at the New York Institute of Art and Design, where artist Robert Henri was his favorite instructor. Hopper would later be associated with the Ashcan School of social realism launched by Henri and his rebellious cohorts, in fact Hopper first exhibited in a 1908 group show in New York organized by some of Henri’s students. Early on in his career Hopper sustained himself by working discontentedly as a commercial illustrator, a profession he positively detested, and it wouldn’t be until the later half of his life that he met with any success as a painter. He sold his first painting at the 1913 Armory Show, and wouldn’t sell another for ten years. His premier solo exhibit in 1920 was a depressing affair that generated neither critical acclaim nor sales. Thankfully Hopper had the fortitude to press ahead with his work despite the difficulties he faced – a determination that should inspire anyone who swims against the conformist mainstream.

Hopper was a private man of few words, and he made but three written statements concerning his views on art. The following quotation came from Notes on Painting, a short discourse published in the catalog of his 1933 retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art:

“My aim in painting has always been the most exact transcription possible of my most intimate impression of nature. If this end is unattainable, so, it can be said, is perfection in any other ideal of painting or in any other of man’s activities. The trend in some of the contemporary movements in art, but by no means all, seems to deny this ideal and to me appears to lead to a purely decorative conception of painting. (….) I believe that the great painters, with their intellect as master, have attempted to force this unwilling medium of paint and canvas into a record of their emotions. I find any digression from this large aim leads me to boredom.”

The Edward Hopper retrospective runs at the Art Institute of Chicago until May 11, 2008.