The Best Picture in the World

In 1925 the famed English author Aldous Huxley wrote “The Best Picture in the World,” an essay about a fresco mural by one of the great masters of the early Italian Renaissance, Piero della Francesca (1412-1492).

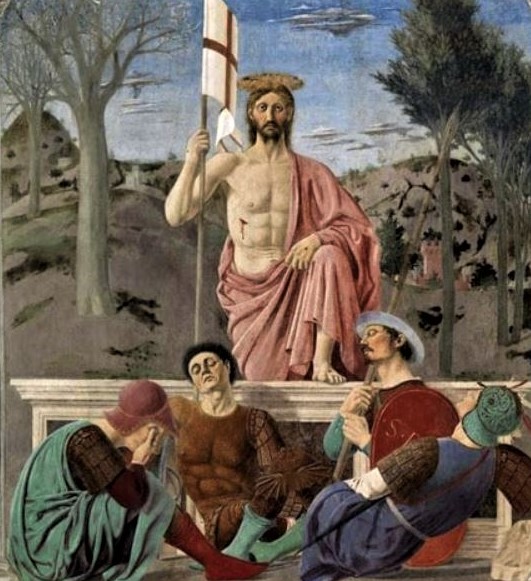

Piero’s mural titled The Resurrection, is recognized as one of the finest religious paintings in all of Christendom.

With careful examination it becomes clear that the master’s hand was guided by a considerable expertise in geometry, in fact the artist was also a brilliant mathematician. The polemic art critic John Berger, once referred to Piero as “The supreme painter of knowledge.”

The genius of Piero notwithstanding, it is Huxley’s belief in an artistic criterion that I wish to concentrate on. In spite of everything his keen observation continues to reverberate in today’s art world, dominated as it is with money and postmodern mediocrities. Here in part is what Huxley noted in his essay:

“The greatest picture in the world…. you smile. The expression is ludicrous, of course. Nothing is more futile than the occupation of those connoisseurs who spend their time compiling first and second elevens of the world’s best painters, eights and fours of musicians, fifteens of poets, all-star troupes of architects and so on.

Nothing is so futile because there are a great many kinds of merit and an infinite variety of human beings. Is Fra Angelico a better artist than Rubens? Such questions, you insist, are meaningless. It is all a matter of personal taste. And up to a point this is true. But there does exist, none the less, an absolute standard of artistic merit. And it is a standard which is in the last resort a moral one.

Whether a work of art is good or bad depends entirely on the quality of the character which expresses itself in the work. Not that all virtuous men are good artists, nor all artists conventionally virtuous. Longfellow was a bad poet, while Beethoven’s dealings with his publishers were frankly dishonorable. But one can be dishonorable towards one’s publishers and yet preserve the kind of virtue that is necessary to a good artist. That virtue is the virtue of integrity, of honesty towards oneself.

Bad art is of two sorts: that which is merely dull, stupid and incompetent, the negatively bad; and the positively bad, which is a lie and a sham. Very often the lie is so well told that almost every one is taken in by it… for a time. In the end, however, lies are always found out. Fashion changes, the public learns to look with a different focus and, where a little while ago it saw an admirable work which actually moved its emotions, it now sees a sham.

In the history of the arts we find innumerable shams of this kind, once taken as genuine, now seen to be false. The very names of most of them are now forgotten. Still, a dim rumor that Ossian once was read, that Bulwer was thought a great novelist and ‘Festus’ Bailey a mighty poet still faintly reverberates. Their counterparts are busily earning praise and money at the present day. I often wonder if I am one of them. It is impossible to know. For one can be an artistic swindler without meaning to cheat and in the teeth of the most ardent desire to be honest.”