Goya: Los Caprichos in Los Angeles

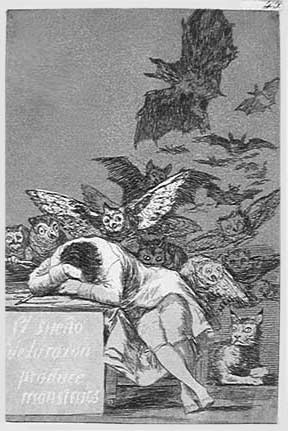

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters. That was the title Spanish artist Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (1746-1828), gave to an etching he created in 1799. The print was Goya’s comment on the lack of critical thinking in Spanish society at the time, the etching part of the artist’s 80 print edition known as Los Caprichos, a suite of etchings that condemned the greed, corruption, and backwardness of church and state in late 18th century Spain.

What makes the Los Caprichos print series such a wonder to us in the early 21st century is not simply that they are works of genius created by a master draftsman and printmaker, or that they depict the appalling history of the Spanish Inquisition; we are enthralled by the prints because, somehow, despite the passing of centuries, the etchings continue to speak of the here and now. Goya’s prints reveal elemental truths about governmental abuses of power, the struggle for human rights, and the perils of ignorance, conformity, and religious zealotry.

In November of 2008 I wrote an article titled, The Enduring Works of Goya, where I brought attention to a traveling exhibition of Goya’s famed Los Caprichos series, which was then making its tenth stop on a national tour of the United States. As of this writing the show is at the small Forest Lawn Memorial Park Museum in Glendale, California, where the prints are to be displayed until August 1st, 2010.

Though it may sound like an unlikely venue, the diminutive museum has a modest but noteworthy permanent collection of art from around the world, which includes Bouguereau’s oil painting, Song of the Angels. The museum has done a superlative job in presenting the Goya prints; on the whole the exhibit is better organized and curated than many of the big shows I have seen at larger museums.

It was the unpredictable quirks and impulses of those guided by superstition or a lust for power that Goya castigated with his etchings. Translated into English Capricho means, “Caprice,” or “Whim,” but while the artist portrayed the follies and weaknesses of individuals in his print series, he always remained cognizant of how larger social forces manipulated and corrupted people. His prints are in essence a stinging critique against placing the interests of the few above the rights of the many – a concept all too relevant for the year 2010.

All 80 etchings from the Los Caprichos series are arranged in the large well-lit entry room of the Museum at Forest Lawn; the prints line the walls as well as a number of freestanding square display columns positioned in the center of the exhibit space. A number of wall plaques provide information on the artist, his works, and the times in which they were produced. Explanatory captions are placed next to the etchings, giving viewers concise information pertaining to the theme in each print. I found many of the descriptive captions for the artworks thought-provoking, so the reproductions of Goya’s prints that accompany this article will include select quotations from the museum’s captions, along with my own commentary.

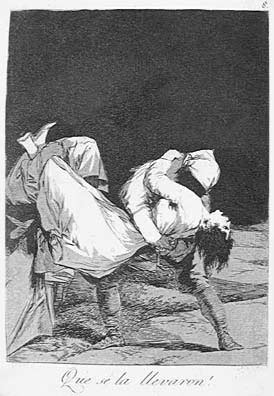

¡Que se la llevaron! (They carried her off). The museum caption reads: “Goya captures the intense action in the abduction of a woman by two men, who may be identified as solicitors of the inquisition, or by death itself.”

The artist captured the elemental horror of a political kidnapping carried out by the state, where a citizen is abducted and held incommunicado.

I cannot view this etching without thinking of “Extraordinary Rendition,” the U.S. government practice of kidnapping suspected terrorists and sending them for “interrogation” in client states where torture is practiced by the authorities.

Extraordinary Rendition was utilized extensively by the administration of George W. Bush, but quietly extended and expanded by President Obama.

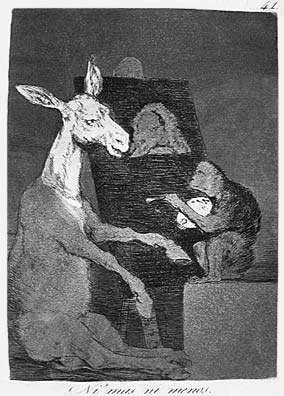

Ni más ni menos (Neither more nor less). The museum’s Gallery Guide booklet wrote that this etching was: “Perhaps the most harsh statement that Goya makes of his contemporaries – those who paint portraits with the intent to please their patrons rather than to depict the sitter in a true likeness.” Goya’s critique was not a trifling matter, but a critical assessment that still bears considerable weight for artists today.

In a comment aimed directly at artists, Goya inscribed at the bottom of his print, “You’ll never die of hunger,” that is to say – those who put themselves in service to the ruling elite and avoid telling the truth will be handsomely rewarded.

Goya portrayed the artist in his print as a trained monkey painting the portrait of an ass, but the simian artist painted the donkey without his long ears, and sporting a powdered wig!

In his notes pertaining to this print, Goya wrote of the aristocratic ass, “He is quite right to have his portrait painted. Those who don’t know him or have never seen him will now know who he is.”

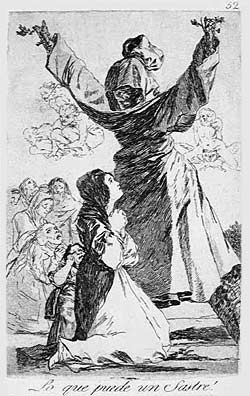

¡Lo que puede un sastre! (Look what a tailor can do!) The museum caption reads: “The scarecrow-like image and caption provided by the artist, gives us a vivid understanding of Goya’s attitude toward superstition and ignorance of those who give credence to such foolishness. Like a vision from Heaven, some people will kneel in prayer to anything, provided it is cloaked in an acceptable form.”

Here I must note Goya’s clever title, which questions the identity of the “tailor,” the one who created and dressed up the scarecrow. Goya understood the tailor to be Spain’s ruling class, which in part held power by sustaining ignorance, reactionary political traditions, and promoting blinkered and proscriptive religious ideas. As it was in the past, so it is today.

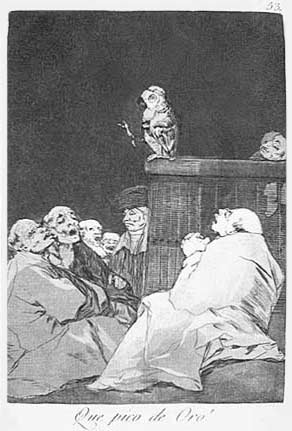

Que pico de oro! (What a Golden Beak!) Goya said of his print: “This looks a bit like an academic meeting. Perhaps the parrot is speaking about medicine? However don’t believe a word he says. There is many a doctor who has a ‘golden beak’ when he is talking, but when he comes to prescriptions, he’s a Herod; he can ramble on about pains, but can’t cure them; he makes fools of sick people and fills the cemeteries with skulls.”

Here Goya used an old Spanish figure of speech that referred to a charlatan making use of flowery rhetoric in order to impress and manipulate the naïve and gullible. To have “a beak of gold” was to posses such oratory skills.

That Goya made his “Golden Beak” a parrot added extra bite to his critique, since a parrot is a masterful mimic of sounds; the artist implying that Golden Beak was simply promulgating the ideas put forth by ruling class circles.

Goya was ambivalent about who his Golden Beak was, an academic, a physician, perhaps a member of the aristocracy? What is certain is that we have our own Golden Beaks today – those who promise “hope” and “change” but deliver war and privation.