Levi Artists: Lay Down Your Brushes

I was startled when printmaker Doug Minkler of Berkeley, California informed me that Levi Strauss & Co., one of the largest clothing manufacturers in the world, was operating an art printmaking workshop in San Francisco.

Minkler, a longtime artist and social activist, was chagrined that the corporate leviathan was whitewashing its poor labor practices by “branding” itself a champion of working people – and using the arts to do so.

This story really begins in 2003, when Levi Strauss & Co. closed the last of its U.S. manufacturing plants, eliminating thousands of good paying jobs for American workers. The company has since moved its manufacturing operations to nations like Mexico, Haiti, Bangladesh, China, and Cambodia, where wages are extremely low and workers easily exploited.

Now, through the efforts of ad firms and PR agencies, Levi Strauss & Co. is promoting itself as a conglomerate that is “a catalyst for change,” and the free printmaking workshop in San Francisco has been part of the marketing campaign. On August 26, 2010, Doug Minkler published an open letter to the arts community titled, Lay Down Your Brushes, entreating artists to reconsider their relationship to Levi Strauss, and to corporate support of the arts in general. The text of Minkler’s dispatch follows:

“Levi Strauss & Co., Wal-Mart’s largest worldwide strategic partner, is just finishing a two-month long advertising event in San Francisco via their Levi’s Free Printing Workshop. Artists from as far as Sacramento and the East Bay have made their way to the workshop to be part of the giant Levi Strauss advertisement campaign. The colorful and talented artists are not printing Levi’s logos, rather, they are printing their own art work. Most of the artists, especially the activists, would never consider creating advertising for the corporate giant, but somehow they have been seduced into helping Levi Strauss.

Some justify their advertising support by working on projects that will benefit non profits, others claim they have not been duped because they are addressing social justice issues on Levi’s tab. A Levi’s workshop exhibit of well known activist artists titled ‘Mission Icons In Time Of Change‘ emerged from the Free Print Workshop in order to raise much needed funds for Plaza Adelante, a Mission self-help center for lower and middle class Latino families. So, what could be wrong with artists and the community finally getting a piece of the corporate pie? I fear a lot.

Artists who accepted the free printing are tacitly saying to both the Levi Strauss corporation and the public that ‘Levi Strauss can use us for cleansing their reputation – their exploitative corporate labor and marketing practices are okay with us. Give us free printing and we will help you sell jeans and a false benevolent image.’ Levi’s co-optation of the artists’ positive image is accomplished by masking corporate advertisement with the legitimizing appearance of involvement in social justice efforts.

In Levi’s cloaked sales campaign, artists are kept far removed from the crass tactics involved in sales, consequently, artists are lulled into thinking that they have not compromised their principles. For the corporation, it is a ‘win win’ situation, but for the non-commercial artist, the ‘For Sale’ jacket they now wear is a problem.

I believe a more critical look at Levi Strauss & Co. is in order before more artists enter into a casual (or not so casual) relationship with this corporate giant.

1. Levi Strauss & Co. is a worldwide corporation organized into three geographic divisions: Levi Strauss Americas (LSA), based in the San Francisco headquarters; Levi Strauss Europe, Middle East and Africa (LSEMA), based in Brussels; and Asia Pacific Division (APD), based in Singapore.

2. By the 1990s, the Levi brand, facing competition from other brands and cheaper products from overseas, began accelerating the pace of its U.S. factory closures and its use of offshore subcontracting agreements. In 1991, Levi Strauss faced a scandal involving six subsidiary factories on the Northern Mariana Islands, a U.S. commonwealth, where some 3% of Levi’s jeans sold annually with the Made in the U.S.A. label were shown to have been made by Chinese laborers under what the United States Department of Labor called ‘slave like’ conditions. Today, Levi jeans are made overseas. Cited for sub-minimum wages, seven-day work weeks with 12-hour shifts, poor living conditions and other indignities, Tan Holdings Corporation, Levi Strauss’ Marianas subcontractor, was forced to pay what were then the largest fines in U.S. labor history, distributing more than $9 million in restitution to some 1,200 employees.

3. The activist group Fuerza Unida (United Force) was formed following the January 1990 closure of a plant in San Antonio, Texas, in which 1,150 seamstresses (primarily Hispanic women), some of whom had worked for Levi Strauss for decades, saw their jobs exported to Costa Rica. During the mid and late 1990s, Fuerza Unida picketed the Levi Strauss headquarters in San Francisco and staged hunger strikes and sit-ins in protest of the company’s labor policies (The above three historical facts about Levi Strauss were resourced from Wikipedia.)

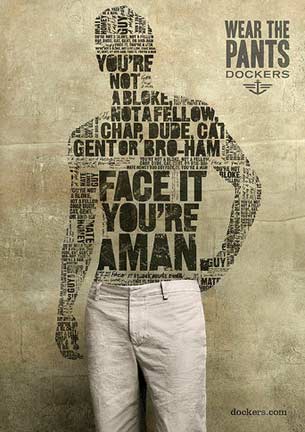

If Levi’s labor practices are not enough reason for you to end your association with them, possibly their recent sexist, homophobic DOCKERS campaign encouraging men to ‘Wear the Pants‘ and welcoming people to ‘MAN Francisco’ will, or their ‘All Asses Are Not Created Equal‘ ad emphasizing variation in butt sizes but continuing to bombard women with images of the unattainable Barbie shape will, or perhaps their ever increasing sexualization of younger and younger girls via their skin tight low rider jeans will, or all of the above will.

In the 90’s, I taught printmaking in the mission at New College of California. One day my class was asked by the administration to create a poster for SF Poetry Week. The first question the students asked me was who were the sponsors? When I informed them that the sponsors were Levi Strauss, Nestle’s and New College, they not only refused the job, but produced protest posters against their college’s involvement. Next, they produced a series of posters that exposed Levi’s U.S. plant closures, their off-shore labor practices and Nestle’s deadly infant formula peddling. These images were either wheat-pasted in San Francisco or hung in the coffee shops in which the poetry events occurred. My refusal to stifle their anger and sense of justice eventually cost me my job.

I am not surprised by Levi’s latest marketing ploy. What I am surprised and disappointed about is how easily such a large number of artists were seduced. To my fellow artists, who oppose the capitalist/corporate model of production and who became artists for reasons other than money, I recommend that you re-evaluate your association with this corporate sponsor and then withdraw your participation.”

Something that author Naomi Klein wrote of in her book, No Logos, seems pertinent to this discussion. Klein noted the omnipresent corporate branding pervading every aspect of life in the U.S., to the point where “walking, talking, life-sized Tommy Hilfiger dolls, mummified in fully branded Tommy worlds,” can be found in all corners of the nation. Klein wrote that the conglomerates behind the marketable brands were less “the disseminators of goods or services than as collective hallucinations.” Artists working at the Levi print shop were aiding – whether they realized it or not – the corporate objective of controlling all public space.

When the Supreme Court voted in January 2010 to strike down restrictions barring corporations from showering political candidates with infinite amounts of money, a substantial number of Americans understood the decision as corruptive to the democratic process. But how is corporate patronage of elected officials all that different from big money sponsorship of the nation’s arts and culture? That is the question one needs to ask when considering the Levi-sponsored printmaking workshop.

The spectacle of Levi Strauss & Co. as a benevolent, socially responsible, and altruistic “corporate citizen” reminds me of a talk given by radical Slovenian philosopher, Slavoj Žižek. His 2009 lecture, First as Tragedy, Then as Farce, examines how charitable giving has become “the basic constituent” of today’s capitalist economy. Žižek contends that “In today’s capitalism, more and more, the tendency is to bring the two dimensions (charity and commerce) together in one and the same cluster, so that when you buy something – your anti-consumerist duty to do something for others, for the environment, and so on, is already included into it. If you think I’m exaggerating you have them around the corner, walk into any Starbucks Coffee, and you will see how they explicitly tell you, I quote their campaign; ‘It’s not just what you are buying – it’s what you are buying into.’ (….) You don’t just buy a coffee, you buy – in the very consumerist act – you buy your redemption from being only a consumerist.”

British artist Andrew Park has brilliantly animated Žižek’s incisive lecture for the British Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufacturers and Commerce (RSA). The First as Tragedy, Then as Farce animation is not only enthralling to watch, it offers an essential critical assessment of the type of “cultural capitalism” now being implemented at the Levi Strauss & Co. print workshop.

I have to mention the “We Are All Workers” marketing campaign launched by Levi’s for its new line of “work wear.” With the U.S. economy at a standstill, unemployment at levels not seen since the Great Depression, and millions of Americans losing their homes, Levi’s is promoting its expensive fashion line with proletarian sensibilities. Poster advertisements displaying slogans like “Everybody’s Work Is Equally Important,” “This Country Was Not Built By Men In Suits,” “Ready To Work,” and “We Are All Workers,” have appeared on city walls all across the United States.

But we are not all workers. Certainly those business executives that made the decision to close every Levis manufacturing plant in the U.S. are not workers, nor were their decisions made in the interests of working people.

Levi Strauss & Co.’s “Wear the Pants” and “All Asses Were Not Created Equal” campaigns were created by Draftfcb, one of the largest advertising agencies in the world, a firm that handles global conglomerates like Boeing, Dow, and Lilly. The “We Are All Workers” campaign was designed for Levi Strauss by the Wieden+Kennedy ad firm. Perhaps the two should be combined for a new “truth in advertising” marketing campaign – “We Are All Asses.”