Review: Four Los Angeles Exhibits

I started 2012 by taking in four exhibits in the Los Angeles area; Art Along the Hyphen: The Mexican-American Generation and The Colt Revolver in the American West at the Autry National Center, as well as Places of Validation, Art & Progression and The African Diaspora in the Art of Miguel Covarrubias: Driven by color, shaped by Cultures at the California African American Museum.

What unites these seemingly unrelated exhibits are the deep insights they provide into the American experience. This review is to encourage those in the Southern California region to see the shows for themselves if possible, and barring that, to do further research on the artists mentioned.

Art Along the Hyphen: The Mexican-American Generation

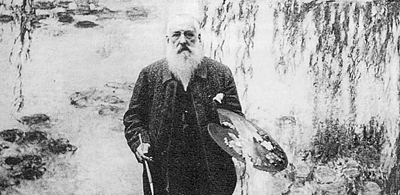

Starting with the Autry National Center, the Art Along the Hyphen exhibit (which ended Jan. 8, 2012), presented the work of six Mexican-American artists who created art in Los Angeles in the post-WWII era of the 1950s and early 1960s; Alberto Valdés, Domingo Ulloa, Roberto Chavez, Dora de Larios, Eduardo Carrillo, and Hernando G. Villa. That these artists are still unknown, even to aficionados of Chicano art, is a testament to the influence of art establishment gatekeepers. It was not just elite art world racism that kept these and other Mexican-American artists out of the museum and gallery systems, it was also the totalitarian supremacy of abstract expressionism that held them in check. The artists in the Art Along the Hyphen show were committed to narrative figurative realism, and that put them squarely at odds with an art establishment obsessed with abstraction.

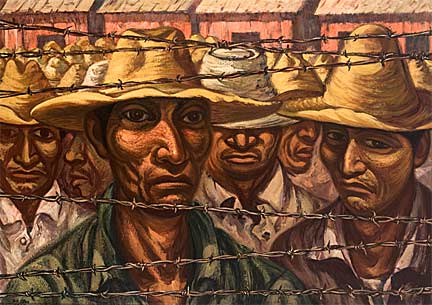

The paintings and prints of Domingo Ulloa (1919-1997) were the most politically charged in the Autry exhibit.

The artist was unquestionably influenced by the 1930s school of Mexican Muralism and social realism; Ulloa in fact studied at the Antigua Academia de San Carlos in Mexico City, the same art academy attended by Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros.

Born in Pomona, California, Ulloa was the son of migrant workers, and after serving in World War II he came under the influence of the Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP – Popular Graphic Arts Workshop), the famous Mexican political left print collective. Every bit as didactic and radical as his contemporaries in the TGP, Ulloa’s art focused on the social ills of American society.

In 1963 Norman Rockwell painted a canvas he titled, The Problem We All Live With. It was a depiction of a 6-year-old African-American girl named Ruby Bridges being escorted through a racist mob by U.S. Federal marshals to the just desegregated William Franz Elementary School in New Orleans, Louisiana.

The real life incident occurred on Nov. 15, 1960, when a large crowd of white racists gathered in front of the school to protest against integration. Armed Federal marshals had to guard the tiny black girl against the angry throng as it chanted “Two, Four, Six, Eight, we don’t want to integrate!” Rockwell’s painting appeared as a double page spread in Look Magazine in 1964, it was a controversial image that would capture the attention of Americans, but Domingo Ulloa had painted a similar canvas six years prior to Rockwell’s original painting.

In 1957 Ulloa painted Racism/Incident at Little Rock, which was based upon real life events that took place that same year in Little Rock, Arkansas. In 1957 a federal court ordered the State of Arkansas to comply with the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown vs. Board of Education decision, which outlawed racial segregation in America’s public schools. Orval Faubus, the Governor of Arkansas and a Dixiecrat (a racist Southern Democrat) resisted the court decision by calling in Arkansas National Guard soldiers to prevent African-American students from entering “white” schools. Republican President Dwight Eisenhower pressured Faubus to uphold federal law and use the Guard to protect black students, but Faubus instead withdrew the troops entirely, leaving black students exposed to attacks by white racist lynch mobs.

When nine black students attempted to enter Little Rock High School on September 23, 1957, thousands of enraged whites assaulted them with stones and fisticuffs. This short video from Marquette University details the incident. In the video you will see footage that I viewed on national television in 1957 at the tender young age of four; the indelible imagery changed my life forever. Although only a four-year-old, I wanted to rush to the victim’s defense. Ulloa attempted to capture all the horror of that ugly affair on his canvas.

Ulloa’s painting is dramatically different from Rockwell’s, it goes without saying that it didn’t appear in Look Magazine. In Racism/Incident at Little Rock there are no government agents deployed to rescue Black school children, there are only six youthful students surrounded by a howling pack of phantasmagorical monsters. The adolescents in the painting huddle together, the oldest of them looking stoic; they have no one but themselves to rely upon. Ulloa’s canvas was inspired by The Masses, a 1935 lithograph by José Clemente Orozco; one could say that Ulloa perhaps borrowed a bit too much from Orozco, or he was simply paying homage to the master. Ulloa’s paintings at the Autry showed that he had not entirely escaped the orbit of the Mexican Muralists; his heavily textured brushstrokes and color palette bearing a striking similarity to that of Siqueiros.

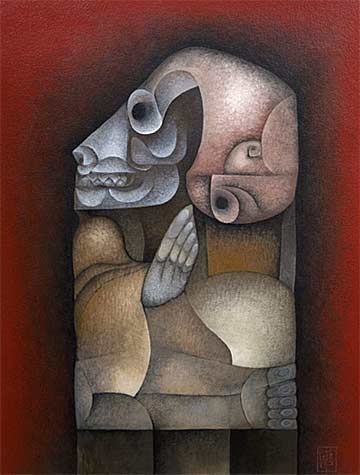

The works of Alberto Valdés (1918-1998) caught my eye. His delicate semi-abstract paintings were filled with vivid color and Pre-Columbian iconography; dreamlike apparitions, mythic creatures, indigenous warriors, and fantastic landscapes.

A small portrait of a fierce imaginary Aztec warrior held me spellbound; painted in muted hues of red and yellow, the face filled the entire diminutive picture plane.

Rufino Tamayo (1899-1991) was an obvious inspiration to Valdés. A handful of Valdés’ paintings achieved a mystical quality where reality melted into intricate webs of translucent primary colors. However, I think Valdés for the most part agreed with Tamayo that a “non-descriptive realism” would counter the “bourgeois” escapism of abstraction. The enigmatic Don Pela Gallos is indicative of Valdés’ opulently painted visions.

The Colt Revolver in the American West

While at the Autry to see Art Along the Hyphen, I decided to visit the museum’s newly opened Greg Martin Colt Gallery, were the exhibit The Colt Revolver in the American West can be found; I knew a rare poster by artist George Catlin (1796-1872) was part of the exhibit. Starting in 1830 Catlin was the first American artist to travel beyond the Missouri River to visit and document indigenous people; over a six-year period he ended up painting more than 325 portraits of individuals from eighteen tribes, some of which had never seen a white man before.

In 2004 the Autry hosted an unforgettable exhibition titled George Catlin And His Indian Gallery that showcased 120 paintings by the artist; needless to say I attended. The exhibit was originally organized by the Smithsonian American Art Museum, which houses the greater part of Catlin’s works in its permanent collection. Ever since first learning of Catlin when I was a teenager, I have maintained a keen interest in his works, and so was pleased to see Catlin’s poster in the Colt exhibit.

Samuel Colt constructed the very first rotating cylinder fed handgun in 1831 at the age of sixteen, a prototype of which is on display in the Autry exhibit. He patented his invention in 1835, and his innovative revolver grew increasingly popular with hunters, frontiersmen, and settlers. Around 1851 Samuel Colt commissioned Catlin to do a series of paintings showing the artist using Colt rifles and pistols during his travels. Catlin’s paintings were reproduced as lithographs, a common practice at the time, and distributed to promote the Colt line of firearms. A total of six different lithographic posters were produced, but only Catlin the Artist Shooting Buffalo with Colt’s Revolving Pistol, is on display at the Autry. Apparently Catlin was one of the very first American artists to promote a commercial product.

While the Autry asserts Catlin’s poster depicts the artist firing a “Dragoon revolver,” I think otherwise. The Colt Dragoon was first produced in 1848, years after Catlin made his 1830-1836 excursions through territory inhabited by the original Americans. The handgun Catlin depicted himself using in the poster looks very much like the model No. 5 Colt “Paterson” Revolver manufactured by Samuel Colt in Paterson, N.J. in the year 1836, a year that fits the time frame of Catlin’s actual travels. In 2011 a rare 1836 Colt “Paterson” sold at auction for $977,500, a world record price for a single historic firearm sold at auction.

Places of Validation, Art & Progression

The California African American Museum (CAAM) offers Places of Validation, Art & Progression, an exhibit tracing the development of artistic expression in the Los Angeles African-American community from 1940 to 1980. On view until Feb. 26, 2012, this large and somewhat unwieldy exhibit covers an important period for L.A. and the United States. The post-war struggle to achieve full human and civil rights for African-Americans, and the social engagement in the arts that accompanied that effort, is a central focus for much of the work in the exhibit.

Concomitant with political shifts in the U.S., Black artists in the 1960s began to explore Africa as an aesthetic wellspring, in addition to taking on a critical examination of Black life and history in America. A good portion of the art on display is in the figurative realist tradition, but the CAAM exhibit also demonstrates how Black artists in the avant-garde used conceptual and installation art in a decidedly political way; here, Betye Saar’s Sambo’s Banjo comes to mind.

The work is a mixed-media assemblage composed of a banjo carrying case displayed to stand open, the outside of the case painted with a contemptibly stereotyped image of a Black man with huge bulging eyes and enormous blood red lips. An examination of the case interior reveals that in the area where the circular body of the banjo would rest, a diminutive “Little Black Sambo” toy figure dressed in red, white, and blue hangs from a tiny noose. Above, in the thin part of the case were the banjo’s fretted neck would be situated, a small black metal skeleton is arranged next to a historic black and white photograph of an actual lynching. A piece of wood carved and painted to look like a large slice of watermelon sits in front of the tableau formed by the banjo case. Altogether, Saar’s assemblage is chilling.

The exhibit contains three works by Charles White (1918-1979), an artist whose works exerted a powerful influence upon me in the early 1970’s.

Three works by White are on display, a small linoleum cut and a larger and quite extraordinary etching, the triad completed by a sizeable oil painting titled Freedom Now.

These three works alone give enough reason to visit Places of Validation, but the CAAM exhibit offers many other treasures.

One of my favorite works in the exhibit is by Ernie Barnes (1938-2009), who was born in North Carolina during brutal racist years.

In 1956 the eighteen-year old Barnes visited the North Carolina Museum of Art while on a field trip; when he inquired of a docent where he might find the museum’s collection of works by Black artists, he was told “Your people don’t express themselves that way.” Barnes would develop into one of America’s premier Black artists and in 1978 would return to the same museum for a successful solo exhibition of his art.

On display at the CAAM is My Miss America, Barnes’ heroic depiction of Black womanhood. Painted in 1970, the canvas portrays a woman made rough by years of drudgery and sacrifice; dressed in a plain red cotton dress she hauls two heavy brown bags with her coarse hands. It is evident the working woman is part of America’s permanent underclass, yet, she exudes the dignity and nobility that evades those thought to be “above” her. The title Barnes gave to his canvas was not based on the notion of woman as trophy, rather, it is an affirmation of the strength, integrity, and leadership of women. If there is a “Miss America,” Barnes showed us where she is to be found.

The African Diaspora in the Art of Miguel Covarrubias: Driven by color, shaped by Cultures

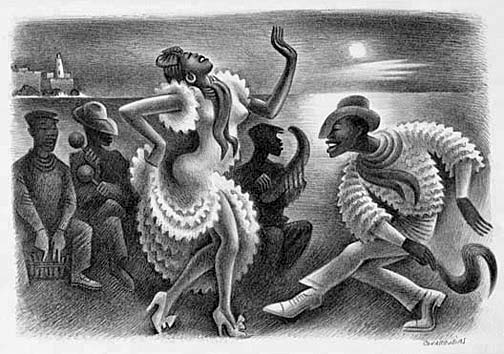

In another wing of the CAAM one can see the works of Mexican artist Miguel Covarrubias (1904-1957). It brings together the artist’s paintings, lithographs, drawings, sketches, and illustrations for books and magazines portraying people of African heritage in the United States, Haiti, and Cuba; but the exhibit also includes portraits the artist made of people while traveling through North, East, and West African countries. Gathered under the thematic banner of The African Diaspora in the Art of Miguel Covarrubias: Driven by color, shaped by Cultures, the exhibit’s primary focus are the works Covarrubias produced in the mid-1920s as an observer of the Harlem Renaissance.

With a grant from the Mexican government, the 19-year old Covarrubias traveled to New York City in 1924 where he became immersed in African-American culture. He met and befriended Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston and other notables from the literary scene, and regularly frequented Harlem’s many Jazz clubs. He produced an endless stream of drawings and other artworks that depicted African-Americans in church, on the street, and going about their everyday lives; to my mind, few non-African-American artists up until Covarrubias had ever been given to such a positive examination of Black Americans. By 1927 a number of these works were published in book form under the title of, Negro Drawings, and more than a few of these original works are included in the CAAM exhibit.

A remarkable painter, printmaker, curator, writer, theatrical set and costume designer, anthropologist, and radical humanist, Covarrubias is mostly known in the U.S. as an illustrator and caricaturist whose celebrity caricatures graced the covers and inside pages of publications like Vanity Fair, Fortune, and The New Yorker in the 1920s and 1930s. But when it came to his depictions of African-Americans, he said the following: “I don’t consider my drawings caricatures. A caricature is the exaggerated character of an individual for satirical purpose. These drawings are more from a serious point of view.”

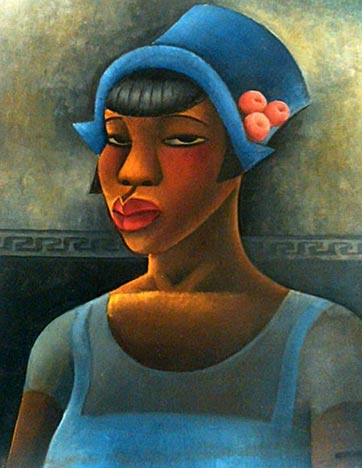

One especially striking painting in the exhibit is Covarrubias’ Black Woman with Blue Dress, an oil on masonite study of a fashionable young woman. One must assume she was a denizen of one of the Jazz clubs the artist haunted, her cool gaze and “Flapper” attire are the mark of an urban sophisticate.

The reproduction of the painting shown here does not begin to do the original justice; Covarrubias made full use of the transparent characteristics of oil paint, his vibrant portrait looking ever so much like a backlit panel of stained glass. Next to this painting, another similarly sized and composed oil portrait stood out conspicuously, a masterful interpretation of a young woman in a deep red dress.

The portrait of the Black woman in the red dress continues to enthrall me, though I did not get the title or date of the painting. The woman wearing a bobbed Flapper hairdo so angular it seemed architectural, was portrayed in silhouette against a background the color of ripe lemons. Thrown into shadow and her beautiful ebony skin painted in the darkest of hues, her features appear hidden, until a closer look reveals that her eyes are staring back at you. Covarrubias’ close-up portraits of North African women are similarly eye-catching and arresting studies that will have me visiting the exhibition a second time before its closing.

I cannot speak highly enough of The African Diaspora in the Art of Miguel Covarrubias, it is one of the best exhibitions I have ever seen in Los Angeles, if only for the fact that the artist’s fine art prints and oil paintings are so little known in the United States. Regrettably the museum offers no printed catalog of this important show, not even an informative pamphlet. The superb exhibition runs until Feb. 26, 2012.