Joni Mitchell and Art Nouveau

This essay is not about the Art Nouveau movement, but it is about famed folk singer-songwriter Joni Mitchell. On March 1, 2023 Mitchell received the Library of Congress’ Gershwin Prize for Popular Song. But first, before I detail my reaction to the award… a repentant confession.

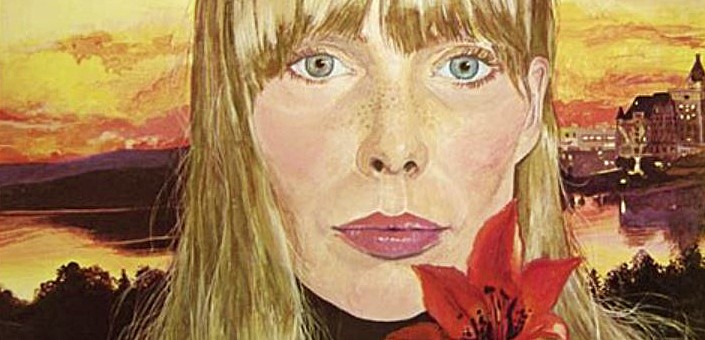

I’m writing this as someone who, once upon a time, was a youthful enthusiast of Joni Mitchell. As a 14-year-old hippie kid in 1968 I bought Song To A Seagull, Mitchell’s premier album of the same year. In 1969 I acquired her second album titled Clouds; I guess you could say I was a fan. She did the artwork that graced those albums, and to my 15-year-old imagination her self-portrait on Clouds was “out of sight.”

Joni and her gentle hippie-style folk music inspired me, so I purchased her 1970 Ladies Of The Canyon album; the song Woodstock was on that record—it was an anthem for the Woodstock nation that came to be popularized by Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. As a 17-year-old, the masterful 1971 Blue was the last album from Joni that I fully enjoyed.

By 1974 Joni was veering into soft rock and jazz and I lost interest. Mind you, I had discovered jazz saxophonist John Coltrane around ’68; I loved his 1961 version of My Favorite Things. Jazz was on my record player at the time; Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis, the great Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong, along with the most extreme psychedelic rock I could find, like Vincebus Eruptum, the premier 1968 album by Blue Cheer. Not to mention, in 1977 I really left hippie behind when I cannonballed into the Los Angeles punk rock scene. Yeah, I know, what a weird kid.

The Gershwin Prize for Popular Song is named after George and Ira Gershwin, it is said by some to be the “nation’s highest award for influence, impact and achievement in popular music.” Joni Mitchell was given the award at the close of a two-hour invitation-only concert held at the D.A.R. Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C. Hmmm, remember what the real folk singer Phil Ochs said about the Daughters of the American Revolution? Never mind.

Singers at the two hour concert included the likes of Annie Lennox, James Taylor, Graham Nash, Cyndi Lauper, Herbie Hancock, Marcus Mumford, Diana Krall, Ledisi, Angelique Kidjo, and Brandi Carlile—all of which performed covers of Mitchell’s famed songs. Excuse me for saying so, but it was a cringe fest par excellence.

Annie Lennox (remember her?) gave a theatrical rendition of Both Sides Now that had Graham Nash jumping from his seat to applaud widely. Then there was Cyndi Lauper of “She bop, he bop, a we bop, I bop, you bop, a they bop, be bop, be bop, a lu she bop” fame. USAToday described her having “lavender hair fashioned into a stylish Mohawk.” When did that symbol of outrage turn into the hairstyle of the blank nouveau riche? Anyways, Lauper sang Joni’s Blue, with a voice “dripping in beauty,” according to USAToday. A lot of things have been said about Lauper’s singing voice, to my knowledge “beautiful” was never one of them.

Plentiful mainstream corporate accounts of the concert and award ceremony mentioned that members of Congress attended; House Speaker Rep. Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif); Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn); Patty Murray (D-Wash); and Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine). But one detail was left out.

Also on March 1, 2023, Joe Biden addressed House Democrats at the House Democratic Caucus retreat in Maryland, but 11 Democratic Congress Critters didn’t attend—instead they attended the award concert for Joni Mitchell. Talk about abandoning Congressional duties!

Punchbowl News reported that “a healthy contingent of House Democrats” skipped Biden’s speech for the Gershwin Awards. Representatives Maxwell Frost (Fla.), Earl Blumenauer (Ore.), Steve Cohen (Tenn.), Dan Kildee (Mich.), Mark Takano (Calif.), Andy Kim (N.J.), Katie Porter (Calif.), Pramila Jayapal (Wash.), Lloyd Doggett (Texas), Hillary Scholten (Mich.) and Greg Casar (Texas) were all at the concert. Come to think of it, who would want to be bored to death at an Uncle Joe snoozefest?

The invite-only concert which included the aforementioned Democrats, will be broadcast by the Public Broadcasting Service as a special titled Joni Mitchell: The Library of Congress Gershwin Prize for Popular Song. It will be aired on March 31, 2023 (peasants, check local listings) as part of the station’s Emmy Award-winning music series. Also, the US armed forces gathering on the border of Ukraine for the premier of WW3 will likewise have a chance to see the spectacle. It will be broadcast to Department of Defense locations around the world via the American Forces Network.

The highlight of the event, or so I’ve been told, was Joni Mitchell performing Summertime, the classic written by Ira and George Gershwin. I fully understand why people would want to shower acclaim upon Mitchell, she is no doubt a talented songstress and composer. So why my testiness regarding Joni and the exultation surrounding her at the Gershwin Prize? It comes down to her shenanigans in the mid-1970s, controversies that I never forgot.

To begin with, in the mid-1970s Joni developed a weird fixation for Black men; I’m not speaking of her admiration for Black musicians like bassist Charles Mingus, pianist Herbie Hancock, and saxophonist Wayne Shorter—a respect that I share with her. No, I am speaking of something that is unequivocally delusional.

In an overly long and fawning Feb. 2015 interview with New York magazine, Joni made a number of bizarre statements, like: “When I see black men sitting, I have a tendency to go, like I nod like I’m a brother. I really feel an affinity because I have experienced being a black guy on several occasions.” She based this notion on a remark from her dentist, who allegedly said while examining her teeth: “Oh, you’ve got the worst bite I’ve ever seen. You have teeth like a Negro male.” I wish I was making this up, but it gets worse.

Afterwards Joni created a doppelganger persona she named Art Nouveau.

Also in the magazine interview, Joni described an encounter with a Black man on the streets of Los Angeles that led her to create her self-same Art Nouveau character. Her stereotypical alter-ego sported a pimp costume—which she wore to a 1976 Halloween party: “I was walking down Hollywood Boulevard when a black guy walked by me with a diddy-bop kind of step, and said in the most wonderful way, ‘Lookin’ good, sister, lookin’ gooood.’ His spirit was infectious and I thought, I’ll go as him. I bought the make-up, the wig, sleazy hat and a sleazy suit and that night I went to a Halloween party and nobody knew it was me.”

At the Halloween shindig, photographer Henry Diltz took a single photo that caught the quiet androgynous looking Black pimp skulking around the room, but really, all those white folks at the swanky soiree couldn’t tell that character wasn’t a white woman in black face? Oh please.

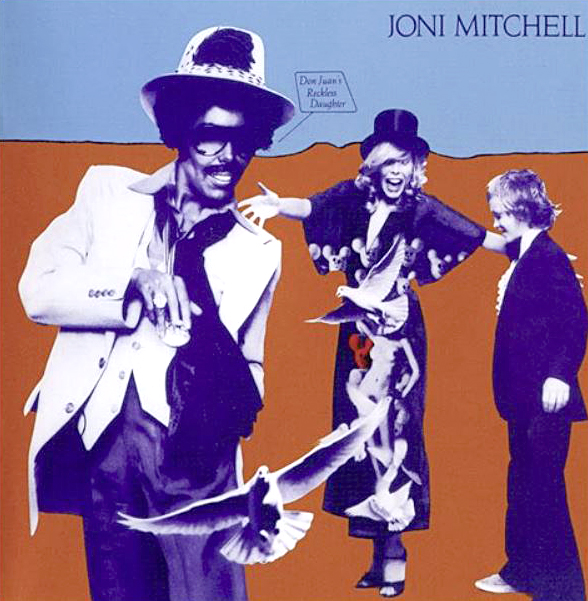

But Art Nouveau wasn’t just a Halloween costume to Mitchell, she dressed up as her kindred soul in a photo shoot for her 1977 album, Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter. The photographer was Henry Diltz, the fellow who snapped the photo of Joni in black face at the Halloween bash. Long afterwards Joni said she thought Diltz was “bossy,” and that she wanted to get back at him.

In her words: “It was great revenge. That was all to get his ass. To freak him out. I had to keep him on the defensive.” All the same, for the countless numbers of people who saw the Art Nouveau’s Reckless Daughter album cover art, who knew the Black magician pictured pulling white doves from a handkerchief was none other than Joni in black face?

That “Halloween party” stuff was a ruse, and the excuse of “revenge” against Diltz was a deception, because eleven years later in 1988 Mitchell directed a video where she dressed up in black face to portray a Black soldier named Killer Kyle—the central character in her tenuous antiwar song, The Beat of Black Wings.

As a protest song the lyrics are rather mundane, but the burnt cork caricature of a Black man makes the music video grueling to watch. It was Art Nouveau in camouflage.

But that isn’t the worst of it.

In Dec. 7, 1975 Joni Mitchell joined Bob Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue traveling music show, along with Joan Baez, Roberta Flack and a host of others (in ’72 Flack and Donny Hathaway had a big hit with Where is the love). The Rolling Thunder review performed before 300 inmates at the Edna Mahan Correctional Facility for Women near Clinton, New Jersey; the concert was designed to draw attention to the imprisonment of Rubin “Hurricane” Carter (1937–2014).

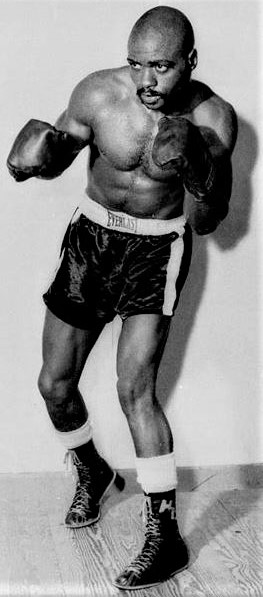

Carter was an African American boxer wrongfully convicted and imprisoned for a triple murder that took place at a bar and grill in Paterson, New Jersey. At the Correctional Facility concert, Dylan and his cohorts performed Hurricane, a song the folk artist had composed that told of the trials and tribulations suffered by the boxer.

Carter became a cause célèbre when Dylan’s 1976 album Desire was released. The record included Hurricane–which received heavy airplay on radio stations across America and became a Top 40 hit that year. I’ll never forget driving on the Hollywood Freeway in 1976, turning on the AM radio, and hearing Dylan crooning the lyrics: “Yes, that’s the story of the Hurricane, but it won’t be over ’til they clear his name.”

Those who performed at the prison concert included Bob Neuwirth (a folk singer who co-wrote Mercedes Benz for Janis Joplin), Mick Ronson (the guitarist in David Bowie’s Spiders from Mars back-up band), Rambling Jack Elliott (Cowboy folk singer extraordinaire), multi-instrumentalist Rob Stoner, and Ronee Blakley (a singer songwriter who played the mom in the 1984 A Nightmare on Elm Street.)

Even the famed counterculture poet Allen Ginsberg appeared on stage to share his poems. The crowd, two thirds of which were Black women, were thrilled with the music-making and ecstatic over the Hurricane song. Then it was Joni Mitchell’s turn to entertain the prisoners.

Mitchell’s performance quickly and spectacularly went awry. The Black audience was unsettled by Mitchell’s jazz and blues riffs, hearing them as inauthentic and insulting. Soon displeasure turned to anger as the audience heckled and yelled abuse at the befuddled Mitchell. Making things worse, in a fit of indignation the lady of the canyon shouted at the concertgoers, Hurricane is a… (insert N-word here). Obviously the furious crowd wasn’t going to put up with that nonsense, it collectively booed a crying Mitchell right off the stage.

I remember that outrage as if it were yesterday, but the moment in American musical history that I have just described has largely been erased from memory.

Remarkably, a brief mention of the event can be found on the official Joni Mitchell website. It comes in the form of an archived article published in 2011 and titled Author discusses race, culture in relation to Joni Mitchell. The author was Eric Lott, a professor from the University of Virginia. Lott’s mention of the correctional facility blowout is found at the bottom of the page, along with this quote regarding Mitchell: “Joni thought she inhibited blackness, that’s why she didn’t see a problem with her wearing blackface or using the N-word.”

After spending almost 20 years in prison, a petition of habeas corpus released Rubin Hurricane Carter from imprisonment. At 48-years-old and his career destroyed, Hurricane was freed without bail in November 1985.

Ever since I was a pre-teen in the early 1960’s I understood the importance of the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. The 1964 Free Speech Movement (FSM) waged by students at the University of California in Berkeley, inspired by my own attitude regarding free-speech rights. On Dec. 2, 1964 Mario Savio, a leader of the FSM, delivered a speech on the steps of the university’s Sproul Hall; he said the following in an excerpt from his oration:

“There is a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can’t take part; you can’t even passively take part, and you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop. And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you’re free, the machine will be prevented from working at all!”

Those words never left me. You could say, they continue to guide me. I have no doubt that young and old today—faced with all the ills of the present, understand and value that address, no matter their political orientation. We still have a First Amendment in America, and as a working artist I am very much aware of how important that is. I don’t want any American to live under a censorious regime that dictates what they can see, read, say, or create. As the old maxim goes, “I may disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” So, I wouldn’t even censor Joni Mitchell.

What perplexes me is this. Historic public statues are being torn down because they are perceived to be racist. Sport mascots and logos are eradicated and redesigned for the same reason. George Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984 is rewritten from a woman’s point of view because the original is “sexist.” Speakers on university campuses have been cancelled because campus radicals see free speech as “hate speech.” All types of works are being redacted, retracted, deleted, expurgated, and tabooed because they are not “inclusive” or fail to stridently advocate “equity.”

But Joni Mitchell gets a pass because she wrote Big Yellow Taxi.

What a strange world we live in.