The Boston MFA & George Jackson

While visiting Boston, Massachusetts in July, 2023, I visited the city’s Museum of Fine Art (MFA). Strolling through the museum’s Art of the Americas wing I happened upon the Artists of African Descent gallery.

I was puzzled by an artwork I found there, an acrylic portrait painting created in the red, black, and green colors favored by black nationalists and exponents of African liberation. It was painted by black American artist, Kofi Bailey (1931-1981) and titled George Jackson. You might ask, “who was that?”

The wall label for Bailey’s painting gave only perfunctory information: artist, title, medium, date, and nothing more. There was no info on who George Jackson was. The same is true for the museum’s webpage on the painting. I was more than a little perplexed by this.

Since the museum didn’t write information about George Jackson, I’ll write if for them… and they’re not going to like it.

Unfortunately the Boston MFA forbids reproducing images found on their website, so I cannot publish their full color image of Bailey’s George Jackson painting. However, I’m providing a link to the MFA’s webpage that displays the artwork, and have posted a historic newspaper photo that shows the George Jackson painting on exhibit in 1972.

Kofi Bailey was a talented artist, known for realistic charcoal and conté crayon drawings of African-Americans. His works were aesthetically linked to those of Charles White, though in my opinion he did not possess the draftsmanship and emotive power of White. Bailey didn’t care much for painting, his art was Afro-centric and his output mostly drawing.

Bailey’s Young Woman from Yoruba is a good example of his artistry. Produced around 1970 with charcoal, graphite, and white chalk, the drawing celebrated a West African woman as a standard of beauty for American blacks—a central aesthetic shared by those involved in the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s.

Bailey’s exaltation of George Jackson had the qualities of a propaganda poster. It seemed out of place, not just in the Artists of African Descent gallery, but in the MFA collection as a whole. It combined an image of a Vietnam era Colt M16A1 battle rifle, with a portrait of Jackson—the black communist revolutionary and Field Marshall of the Black Panther Party.

It’s no mystery that the Democrats who run Boston and the rest of Massachusetts are stridently in favor of gun control; one must assume the ultra-liberal Boston Museum of Fine Art concurs with that opinion. Why then did it exhibit an artwork that lauds the M16?

Since the progressives of the MFA mounted a portrait of George Jackson, you’d think they’d have the confidence and honesty to mention that he was an anti-capitalist revolutionist who argued for armed urban guerrilla warfare in America, but then perhaps that would have been… a little too honest.

Bailey rarely created artworks that were overtly political. In 1968 he was commissioned by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), to create a poster announcing the Poor People’s Campaign of ’68. He created a charcoal drawing for the poster that portrayed working class blacks crowding around Martin Luther King, Jr.

King and the SCLC intended the campaign to be a “multiracial army of the poor,” that would march on the nation’s capital to nonviolently demand the country’s poorest people—from the deep South to Appalachia, be given relief and opportunities. On March 4, 1968, King, the president of the SCLC, would be photographed holding Bailey’s poster; the artwork was printed in the 1000s and widely distributed across the USA.

As part of the effort to build the Poor People’s March in Washington DC, Martin Luther King, Jr. travelled to Tennessee to support the Memphis sanitation strike, where black workers demanded better treatment and higher pay. While there he stayed at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis.

King never got to attend the Poor People’s March. On April 4, 1968, an assassin’s bullet found him on the second-floor balcony of the Lorraine Motel. He was only 39-years-old when he was struck down. Despite his insistence on non-violent tactics, his killing set off burning, looting, and rioting in 110 American cities.

Prior to King’s killing President Kennedy was assassinated on Nov. 22, 1963, and Malcolm X was assassinated on Feb. 21, 1965. After King’s murder Senator Robert F. Kennedy was killed by an assassin on June 4, 1968. US cities were on fire, the war in Vietnam was raging out of control, and many young Americans were turning hard-left politically… which brings me to the story of George Jackson.

As a 15-year-old in 1968, I bought the just published book, Soul on Ice. It was written by Eldridge Cleaver while in Folsom State Prison in 1965. Paroled in 1966, Cleaver joined the Black Panther Party in 1967. On the strength of his writings he became the Party’s Minister of Information. Soul on Ice was released in ’68 and became a national best seller. That same year Cleaver ran for US president on the Peace and Freedom Party ticket.

Reading Cleaver’s book I was astonished at how quickly he transformed from a felonious antisocial criminal to a defiant Marxist revolutionary… some said there was no difference.

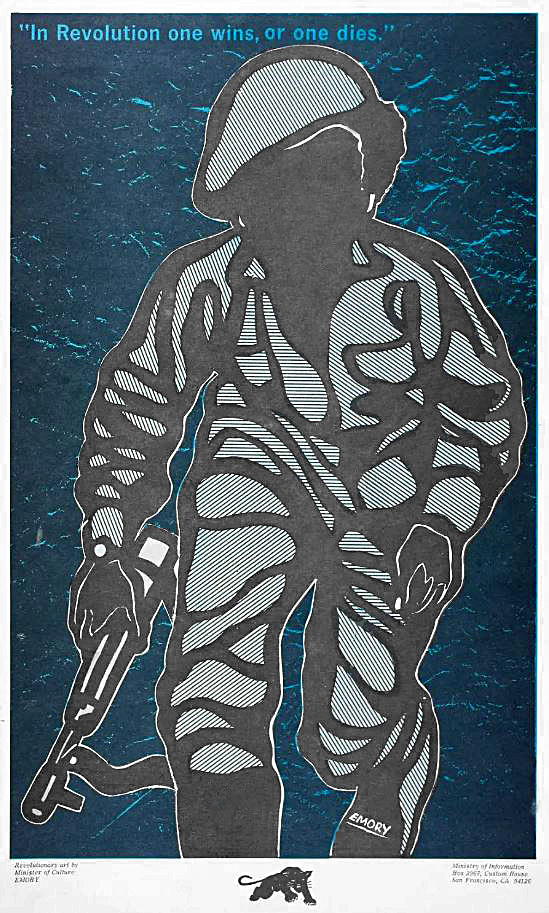

A newsstand near my home sold The Black Panther, the party’s weekly newspaper filled with diatribes against capitalism, imperialist war, and domestic police brutality. It was filled with drawings by Panther artist Emory Douglas—whose works portrayed police as pigs and ghetto inhabitants as righteous urban guerrillas armed with machine guns and hand grenades. I first learned of George Jackson from The Black Panther.

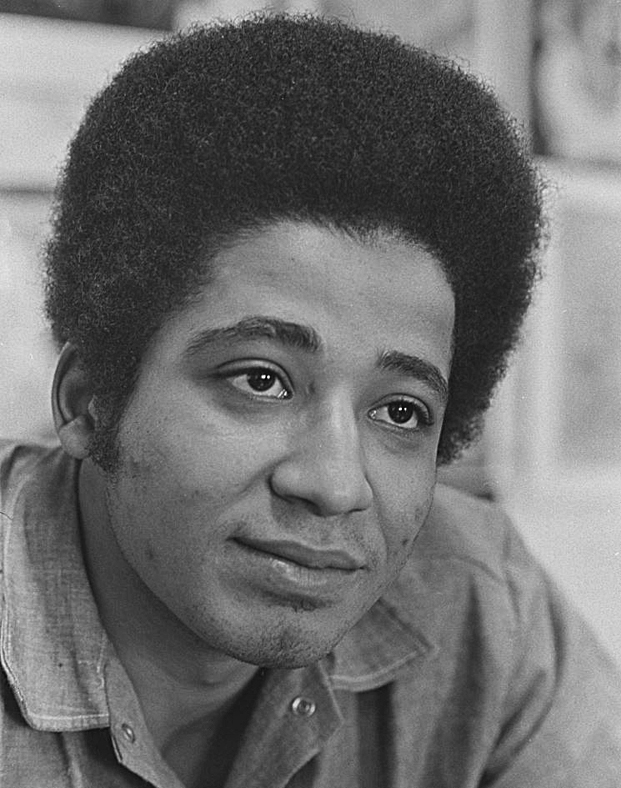

George Jackson (1941-1971) was born on the West Side of Chicago; he was the son of a postal worker named Lester Jackson. As a pre-teen George became a petty thief that committed assorted crimes. At 14 he was arrested for stealing a purse. In 1956 Lester attempted to straighten out his son by transferring to a postal job in Los Angeles. It was to no avail.

In LA, George fell into a street gang called the Capones and his criminal activity increased. He was arrested for numerous offenses, but always released to his father as he was still a minor. Eventually he became an incorrigible and prolific lawbreaker.

At the age of 18 in 1960, George was an accomplice to a gas station robbery in LA, 70 dollars was stolen (equivalent to $700 today). Caught by the police, he pleaded guilty to second degree robbery and was given an indefinite sentence of one year to life. He was only 19-years-old when he entered prison. He would spend eleven years there—his entire adult life, with seven of those years spent in the hell of solitary confinement.

George was sent to a male only correctional facility located in Monterey, California known as Soledad Prison; in 1962 he was transferred to San Quentin State Prison in Marin County, California. He entered prison a functional illiterate, but taught himself how to read. In San Quentin he began reading history and law, but had a predilection for political theory. In his own words:

“I met Marx, Lenin, Trotsky, Engels, and Mao… and they redeemed me. For the first four years, I studied nothing but economics and military ideas.”

Much like Malcolm X who entered prison a 20-year-old unable to read, and became literate by reading a dictionary one definition at a time—so too George sharpened his intellect with books. Unfortunately he filled his head with the wrong ideas. He was soon writing Marxian position papers on all manner of subjects, and received the attention of prison convicts as well as prison authorities.

Meanwhile in the California Penal Colony of San Luis Obispo, California, Huey P. Newton, founder and leader of the Black Panther Party, was imprisoned in 1967 awaiting trial for the killing of an Oakland police officer. Prisoners there told Huey about a brainy inmate in San Quentin, his name was George Jackson.

Later, Huey P. Newton got word from the prison grapevine that George wanted to join the Black Panther Party, and so he was inducted, given the honorary title of Field Marshal, and put in charge of recruiting prisoners into the Black Panther Party. Newton was eventually convicted of voluntary manslaughter and given a sentence of two years to life, but in 1970 his conviction was overturned on a technicality and he was set free.

Around this time Eldridge Cleaver permitted photographers Pirkle Jones and Ruth-Marion Baruch, to document the Panthers and their activities in the Oakland, California area. The married couple spent several months producing what became a historic photographic essay. Consequently, as part of the series, Ruth-Marion Baruch turned her camera towards the imprisoned George Jackson. He appeared resolute, clear-eyed, fearless… an ill-fated man with a winning smile.

In 1968 George was transferred back to Soledad. On Jan. 13, 1970, fourteen black convicts in the exercise yard of Soledad Prison got into a fight with 2 members of the white supremacist Aryan Brotherhood. From above the yard, prison guard Opie Miller used a rifle to shoot and kill three of the blacks and wound one of the whites. The next day a guard named John Mills was found beaten to death in the prison, presumably in retaliation for the killing of the black prisoners.

On Feb. 14, 1970 a Monterey County Grand Jury indicted George Jackson, Fleeta Drumgo, and John Clutchette for the murder of officer Mills. The three were dubbed the Soledad Brothers by left radicals who began a campaign to free them. Notable liberals like actress Jane Fonda spoke out on behalf of the Brothers, but it was Angela Davis and George’s younger brother Jonathan Jackson who were at the forefront of the movement.

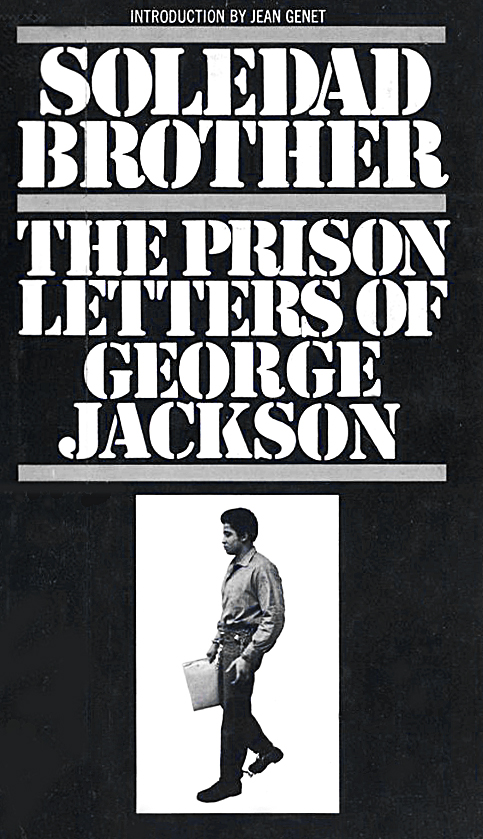

I was 17-years-old when Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson was published in Oct. 1970. It became a national bestseller. I purchased a copy and read it cover to cover. Simultaneously edifying and excruciating—the writings were the voice of a doomed man.

Soledad Brother contained letters George wrote between the years 1964 and 1970 to his father, mother, lawyers, friends, supporters, and younger brother Jonathan Jackson. Jonathan had been killed in an act of terrorist violence he carried out in August of 1970, but I’ll get to that later.

The book also included George’s letters to Angela Davis; they were tender and romantic—and he openly professed his love for her. In 1969 Davis had been fired from her UCLA professorship by the University Regents for being a member of the Communist Party USA.

I must clarify that Angela Davis was never a leader of the Black Panther Party founded by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, nor was she a member in good standing. In her 1974 autobiography Angela Davis, she stated that she joined the Communist Party USA in July of 1968. Thereafter she decided to “go into the Panther Party” to assist their “political education program.” A year later she broke her “relatively close ties with the Panthers” because she thought the Communist Party USA was a politically superior organization.

The introduction to Soledad Brother was written by the radical French playwright Jean Genet. George was in the limelight and the American left lionized him. His letters made clear his political philosophy had gelled into one that demanded armed struggle to crush “Amerikan fascism.” He wrote of Jonathan’s death in a letter dated August 9, 1970. An except reads:

“We reckon all time in the future from the day of the man-child’s death. Man-child, black man-child with submachine gun in hand, he was free for a while. I guess that’s more than most of us can expect.

I want people to wonder at what forces created him, terrible, vindictive, cold, calm man-child, courage in one hand, the machine gun in the other, scourge of the un-righteous—‘an ox for the people to ride’!!!”

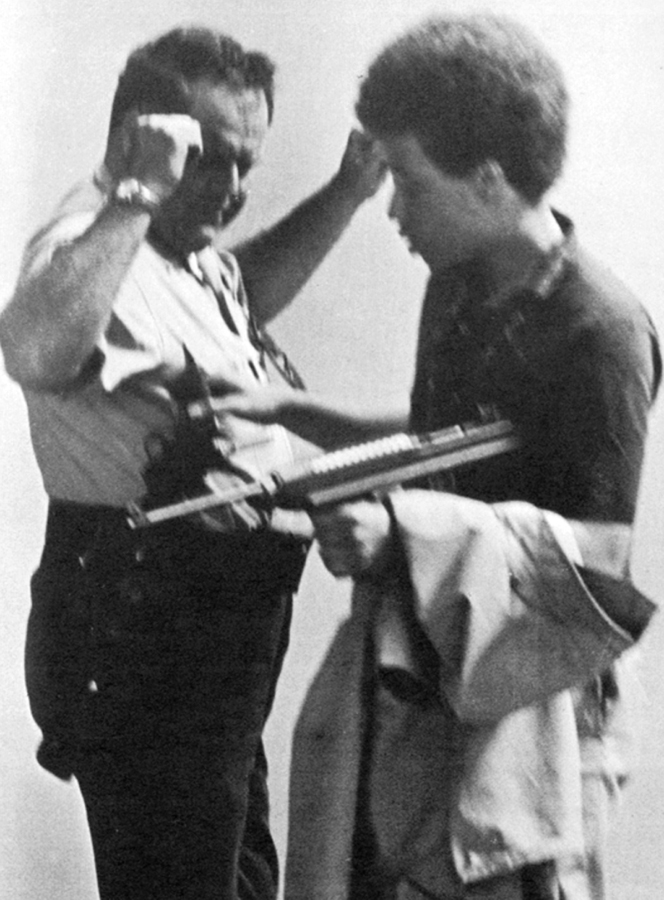

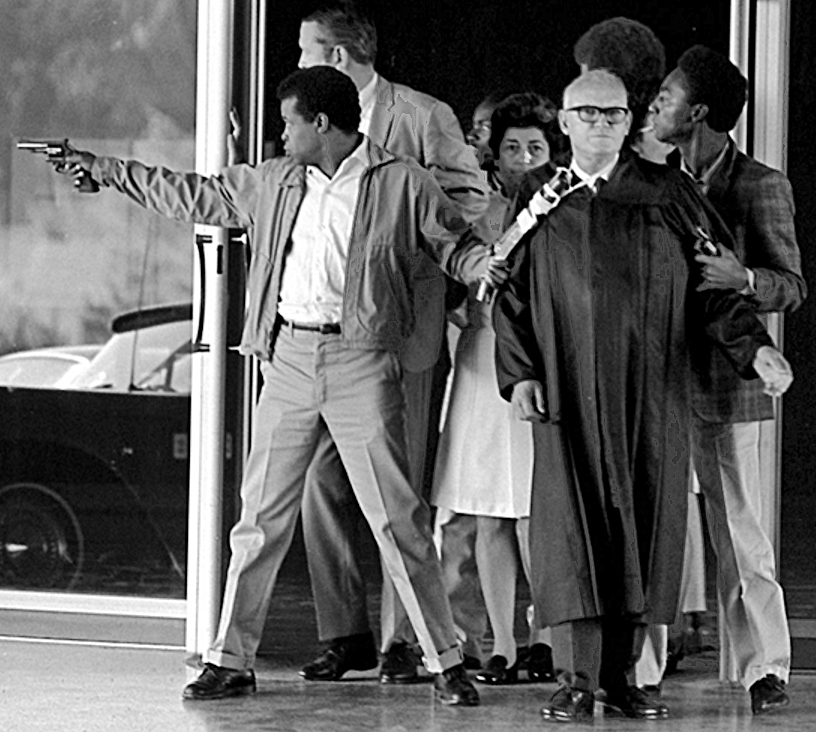

Jonathan was 17-years-old when he led an armed attack on the Marin County Courthouse on Aug. 7, 1970. He meant to take hostages and use them to secure the release of the Soledad Brothers—which included his brother George. Black San Quentin prisoners Ruchell Magee and William Christmas were in the courtroom Jonathan picked, they were testifying on behalf of James McClain, a fellow black inmate on trial for stabbing a San Quentin prison guard.

Jonathan entered the courtroom with a briefcase full of ammo and extra magazines. Under his long coat he hid a sawed-off shotgun and a semiautomatic .30 caliber M1 Carbine with a collapsable stock. He stood in the courtroom, raised his hand holding a 380 Browning automatic pistol, and announced: “All right, gentlemen. Just hold it right there.” He offered weapons to the five black prisoners in the courtroom—three accepted them.

Jonathan handed guns to Ruchell Magee, William Christmas, and James McClain, then the desperados disarmed the courthouse police, relieving them of their 12 gauge shotguns and .357 magnum revolvers.

The insurgents seized Superior Court judge Harold Haley, and used adhesive tape to attach the barrel of the sawed-off shotgun to his neck. Deputy District Attorney Gary Thomas was also taken hostage, along with 3 female jurors. A court reporter had a front row seat of the unfolding attack, and left his chilling account for future generations. Newspaper reporters on the scene were invited by Jonathan to take photos, he told them: “You can take our pictures. We are the revolutionaries.” The images shocked the nation.

As the outlaws and their hostages began to leave the courtroom, Jonathan yelled: “We want the Soledad brothers freed by 12:30!” The group made its way to their rented van, piled in, and Jonathan attempted to drive off. It’s not certain who fired the first shots, but a shoot-out occurred. Court police exchanged fire with the urban guerrillas.

When the shooting stopped Jonathan, McClain, Christmas, and Judge Haley were dead. Magee had pulled the trigger on the shotgun taped to Haley’s neck. Then DA Thomas, who was shot in the spine, grabbed the revolver from the dying Jonathan and shot Magee. The 3 female hostages survived, but one received a gunshot wound to her arm. DA Thomas was crippled below the waist for life. Magee survived his wound but got a life sentence for kidnapping.

After the raid it was shown that the guns Jonathan used, the carbine, pistol, and shotgun (to make it concealable he shortened the barrel), were registered to Angela Davis. She instantly went underground and was a fugitive for two months. The FBI put her on the 10 Most Wanted list and finally caught her in New York City. Based on her supplying guns to Jonathan, she was charged with aggravated kidnapping, first-degree murder, and criminal conspiracy.

To top it all off, in Oct. 1970 the Weather Underground detonated a bomb in a woman’s bathroom at the Marin County Courthouse. The terror bombing was meant as an act of solidarity with Jonathan Jackson’s raid.

On June 4, 1972, an all white jury acquitted Angela Davis of all charges, and she was set free.

Soon after the Marin carnage, George Jackson was sent back to San Quentin in 1971 to await trail for the murder of officer John Mills. That year George completed a second volume of writings he titled Blood In My Eye; the wordsmithing therein was as ominous as the book’s title. His account of prison life and his prognostications of America’s future were full of hellfire. He was an apocalyptic writer, and his eloquence was of the shadowlands. In an essay from Blood In My Eye, he wrote:

“Total revolution must be aimed at the purposeful and absolute destruction of the state and all present institutions, the destruction carried out by the so-called psychopath, the outsider, whose only remedy is destruction of the system. This organized massive violence directed at the source of thought control is the only realistic therapy.”

I don’t mean to sound flippant, but perhaps the Boston Museum of Fine Art would like to use the above quote for its wall label text describing Kofi Bailey’s George Jackson artwork.

Huey P. Newton called George, “The greatest writer of us all.” In 1973 Newton would publish his autobiography titled Revolutionary Suicide. It could also have been the title of George Jackson’s last book. George completed his manuscript for Blood In My Eye just days before he died in California’s San Quentin prison during an attempted escape. His book was published posthumously in January of 1972.

As for George Jackson’s August 21, 1971 prison break. Authorities said George met with his attorney Stephen Bingham in a secure area of the prison designated for visitations. Bingham reportedly snuck a large, two and a half pound, all steel, Spanish Astra 9 mm pistol into the prison, which he purportedly slipped to George.

Prison officials claimed Jackson concealed the gun under an Afro wig. When officer Rubiaco escorted George back to his cell he noticed something in George’s hair and asked him to remove it. Officials said George pulled the gun from under the wig and forced officer Rubiaco to open the cells on the block. Seventeen blacks, four whites, four Chicanos, and one Puerto Rican were freed. Mayhem ensued.

Officers Jere Graham, 39, Frank DeLeon, 44, and Paul Krasnes, 52, were killed and dumped in George Jackson’s cell. They had been strangled with electric cord and their throats were cut with a makeshift knife made from a razor blade attached to a toothbrush.

Officers Rubiaco, McCray, and Breckenridge were shot and stabbed, then tossed onto the pile; they survived. Two of the four white prisoners, John Lynn, 29, and Ronald Kane, 28, were killed by having their throats slashed. One of the lifeless bodies was found in Jackson’s cell, the other was left just outside it. The remaining two whites managed to avoid the breakout altogether by hiding in their cells.

George found the keys to the Adjustment Center’s exit. He unlocked the doors and he and a fellow inmate ran to the prison yard. George was killed when a guard on a balcony gun walk overlooking the yard shot him with a rifle. The first bullet hit George’s left ankle and passed through it. The second struck the top of his head, travelled down the front of his spine, and exited his lower back. George was 29-years-old when he was killed.

So ended the tale of George Jackson… or so it seemed.

His attorney Mr. Bingham vanished and lived for 13 years as a fugitive. He faced trial ultimately, and was acquitted of smuggling the pistol to George. Theories abounded, did prison officials set George up for assassination? Who’s to say? Famed author James Baldwin remarked “no black person will believe George Jackson died the way prison officials say he did.”

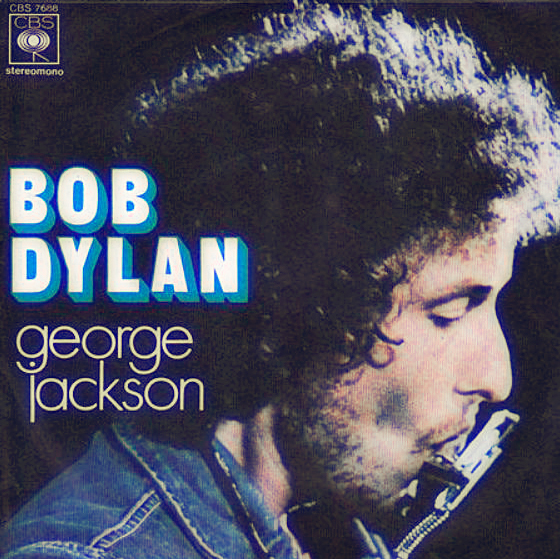

After George’s killing, Bob Dylan released a vinyl 45 RPM single on Nov. 1971 titled George Jackson. On the a-side Dylan performed the song acoustically with guitar and harmonica, on the flip-side he sang the song accompanied by a full band. The song was broadcast on commercial radio, and became number 33 on the Billboard Top 100 chart. Dylan sang that prison guards killed George because “they were scared of his love.” Let’s just say Dylan’s song was pretty thin gruel when it came to the facts.

There are those today, mainly leftwing radicals, who refer to the Marin Courthouse attack and the San Quentin breakout as “slave rebellions.” Others fantasize that George Jackson’s spirit fanned the flames of the George Floyd riots that burned America in 2020-2022. Some pray a waking nightmare like George will not visit us again. Most simply never heard of him.

I didn’t want to dredge up terrible memories by writing this essay… but the irresponsibility of the MFA forced my hand.

To add insult to injury, there was a special Juneteenth “Spotlight Talk” held at the Boston MFA on June 20, 2022. Chenoa Baker the “empathetic curator” and “descendant of self-emancipators” (her words), stood in front of Kofi Bailey’s George Jackson painting, and referred to George as “a Marxist and Black Nationalist thinker.”

The Black Panther Party was not a black nationalist organization, and George Jackson was not a black nationalist thinker. The Panthers were a militant socialist organization that rejected black nationalism and sought alliances with whites; whereas black nationalists regarded all whites as oppressors. A rival group in the black community that opposed the Panther Party was the black cultural nationalist “US Organization” founded and led by Maulana Karenga.

Karenga was the real “black nationalist thinker.” He declared that American blacks could only achieve liberation by taking a Swahili name, wearing African-style clothes, and reconstructing African rituals in the US. It should not be forgotten that on Jan. 17, 1969, a founding member of the Los Angeles chapter of the Black Panther Party, Bunchy Carter, along with the leader of the LA chapter John Huggins, were shot to death by members of the US Organization on the campus of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

In a 1968 interview, Huey Newton bluntly evaluated the black nationalism of Karenga: “Cultural nationalism, or pork chop nationalism, as I sometimes call it, is basically a problem of having the wrong political perspective (….) In other words, they feel that the African culture will automatically bring political freedom. Many times cultural nationalists fall into line as reactionary nationalists.” So, for better or worse, the politics of the Black Panther Party are forgotten, while Maulana Karenga’s made-up black alternative to Christmas known as Kwanzaa, is commodified and celebrated… even by Vice President Kamala Harris. Feel liberated?

In the Art of the Americas wing of Boston’s MFA, there is an elegant but empty gilded wood frame hanging on the wall. Next to it is an oversized wall label with a headline that reads “Who is Missing?” The long-winded text chastises the wing’s American Revolutionary War paintings as showpieces created “for wealthy white elites.” The text explains:

“This empty picture frame represents the many people in the Revolutionary period who were never painted—or heroized—in oil on canvas.”

The Boston MFA has a huge collection of art from Europe, Africa, Asia, Latin America, Ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome, as well as works from Polynesia, Indonesia, and Micronesia. In all of those civilizations rulers used artists to flatter and mythologize themselves in paintings and sculptures. Yet the MFA did not post large wall labels to denounce them for it—that was only applied to the USA.

World history is suffused with war, imperialism, colonization, and slavery. Elites of Europe, Africa, Asia, and Latin America all committed such crimes. These conquerors never “painted—or heroized” subjugated people. For some reason the MFA did not denigrate them with a moralizing wall label.

With its wall label the MFA lamented that African and Native Americans were missing from the paintings of America’s Revolutionary War period. They asked “should we see the face of Crispus Attucks?” But they didn’t mention that Paul Revere commemorated Attucks in his famous engraving The Bloody Massacre, which depicted British soldiers shooting and killing five American patriots on March 5, 1770.

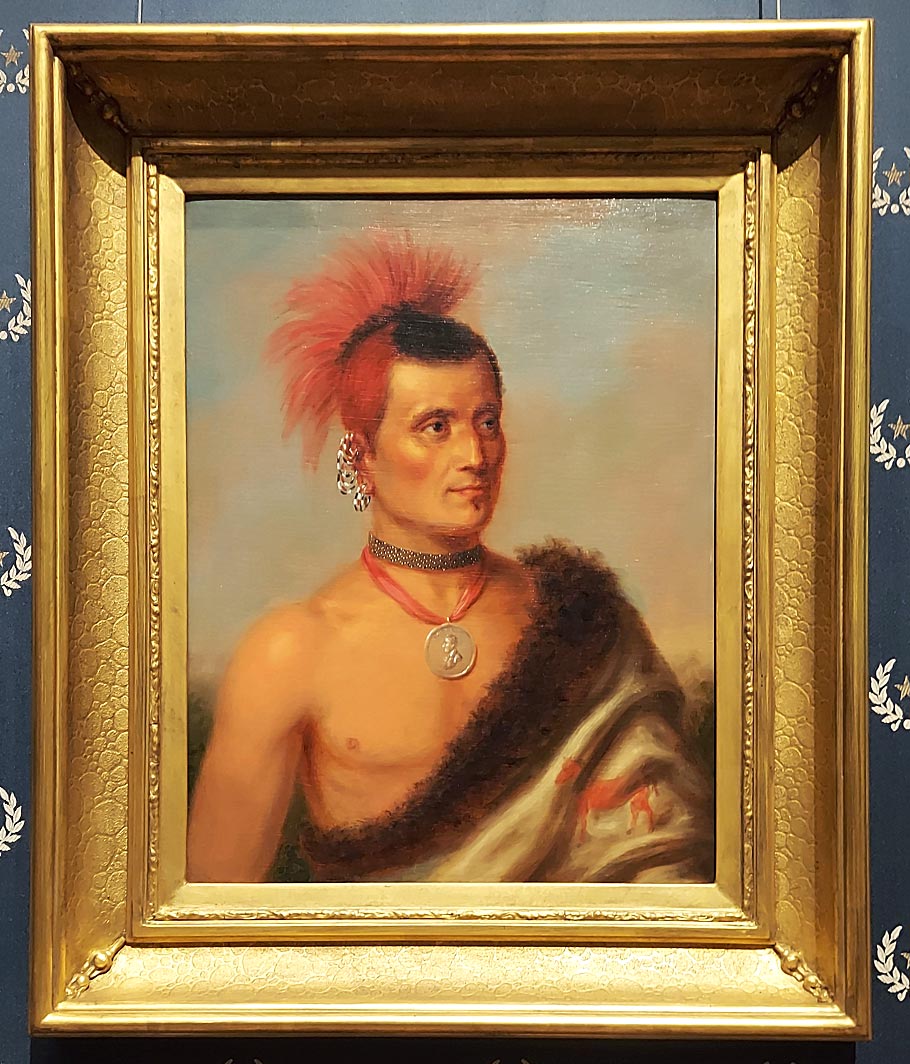

The MFA’s wall label insisted: “There is no portrait of Sachem Solomon Uhhaunaunauwanmut (‘King Solomon’), who led Stockbridge Mohican soldiers against British forces in early Revolutionary battles.” While there isn’t a painting of chief Soloman in the MFA, in the same gallery where the label hangs there is an 1823 oil on canvas painting of Pawnee chief Pes-ke-le-cha-ko, painted by Charles Bird King (1785-1862).

The MFA wall label complains that “colonial portraits were more aspirational than documentary,” that artists “wanted to show off their skills,” that sitters having their portraits painted “wanted to appear confident, worldly, and beautifully dressed.” And the wealthy “projected their ideas of prosperity and power” through art. For goodness’ sake MFA, you’re not describing America’s 18th century Revolutionary War period, you’re describing the billionaire globalist donors who fund your museum!

The MFA wall label ended with the question: “Who do you want to see?” I insist that an art museum’s mission is not to pander to public taste. Art museums exist to collect, preserve, study, and present truly outstanding artistic achievements; all for the uplift and enlightenment of society.

While the MFA does not yet have a special gallery dedicated to those “who were never painted—or heroized—in oil on canvas,” the museum has given us a politically correct empty wooden frame with a rhetorical wall label that queries…

Who do you want to see?

The Boston Museum of Fine Art answered its own inquiry with the image of George Jackson.